When working in the “Africa” storage spaces in the Ethnological Museum in Berlin1, I was immediately confronted with Hans-Joachim Radosuboff’s traces. In his role as the “Africa” department’s storage manager (Depotverwalter), between 1991 and 2012, Radosuboff had reorganised the storage spaces dedicated to objects from the African continent. Organised by topic, similar objects were neatly arranged next to each other. Opening the cupboards, taking out objects to properly look at them, I imagined hearing the storage manager’s successor sigh as I had heard so many times before: once something was taken out, it was not always easy to reconstruct the complicated hanging system that Radosuboff had put in place. Beautifully installed, the objects would not touch each other, draped and arranged behind glass following what he called “movement and aesthetics”.

I met Hans-Joachim Radosuboff in January 2015, after he had responded with enthusiasm to my interview request. He had prepared well for the interview, his speech was accurate and detailed, spiced with funny details. This text is based on this conversation and walk-through of the storage space, several following phone calls, as well as his website, which he has turned into two self-published booklets since.2

The museum as peopled organisation

Instead of attributing space to Hans-Joachim Radosuboff’s narrative in the footnotes, as most research on seemingly mundane and technical work would do, this text makes an argument for the museum as “peopled organisation” (Morse, Rex, and Richardson 2018:116). Seeing the museum as peopled counters understandings of the museum as homogeneous, neutral and anonymous. It emphasises how museum staff contribute to, resist, and produce the museum – especially if people spend entire careers in one place. By revisiting key moments of Radosuboff’s two-decade-long career as storage manager, I reflect on what it means to be responsible for 75 000 objects, the number of objects stored in the “Africa” department of the Ethnological Museum. In particular, I concentrate on forms of agency in the collection, and the collection items’ switching status between object and subject. I am thus focussing on the organisational histories in the Museum in Berlin, making however larger arguments about the effect of museum life on objects usually identified as “ethnographic”.

Creating order

When Hans-Joachim Radosuboff arrived at the Museum, he was confronted with an exceptional situation. In 1990, it was publicly revealed that Leipzig’s Museum für Völkerkunde had kept 45,000 of the Berlin Ethnological Museum’s objects as a state secret. These objects had been given to the government of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) by the Soviet Union in 1975, and stored secretly in a temporary exhibition space in the Leipzig museum, consisting of war booty from the Second World War. The anthropologist Philipp Schorch describes how the GDR government accepted this “return” on German territory, “thus metamorphosing from victory trophy over Nazi Germany to material symbol and marker of friendship between brother states in order to stabilize the Cold War” (Schorch 2018). After the revelation, it was decided to return the objects to Berlin. As put by Christian Feest in 1991, “[n]o sane museum ever acquires 45,000 objects in a single stroke” (Feest 1991, 32). To house them, the Leipzig Hall (Leipzighalle), a storage space, was constructed to store the objects intermediately, before inventorying them and assigning them to the Museum’s different departments. They arrived only a few days after Hans-Joachim Radosuboff had started in the Museum. ”The door swung open, two of my colleagues stood there with these huge carts, filled with objects from Leipzig. ‘Achim, your first objects are here!’“ 25 000 objects from Leipzig faced Hans-Joachim Radosuboff, meant to integrate the “Africa” collections, adding up to another 50 000 objects already present.

Radosuboff arrived “out of the blue” in the Museum. ”This was the time when the Wall just had come down. Anyone applied for anything.” He had worked as a mason, a craftsman and as a guard in the guardhouse at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Berlin (Kunstgewerbemuseum). Calling himself an “auto-didact”, he was left by the contemporary curator of the collection, Hans-Joachim Koloss, with the responsibility to deal with the collection. “Koloss gave me a few brief explanations. When I started to ask interested questions, he was suddenly gone. That’s how it was! In that sense, he was not an instructor! And after a few questions and a few gruff answers I told myself: ‘OK, you have to do your own thing.’“

Fig. 1 Hans-Joachim Radosuboff, in 1992, describing this image as follows: “No PC, writing index cards until the fingers hurt.”, photograph: Hans-Joachim Radosuboff.

In his diaries, Radosuboff wrote: “Only the humble question remains: ‘Where to put things?’ It certainly doesn’t fit in a hatbox.”3 Together with Hans-Joachim Koloss, they found a timely solution. Given that the Museum’s air-raid shelter in the cellar was out of use due to the end of the Cold War, they decided to reuse it as storage space. In order to have clearly distinct entities in the two different storage spaces – one located in the building’s cellar, the other one under the same building’s roof, Radosuboff separated the regional collections within the “Africa” collection. He dedicated one space to the “East Africa” collections and the other to the other collections associated with the continent, which consisted mainly of objects described as stemming from “West Africa”. The collection manager described his dream of the study collection with the “most important rule” being that one could see all the objects, that there was no need to touch them, and that no object touches another.

Fig 2 and 3 : Image caption from the diary Museographie 1: “I needed to put such stuffed cupboards in the hallways in order to retain the masses of objects arriving from Leipzig”, 1992, photographs: Hans-Joachim Radosuboff.

The entire collection needed reorganisation, and in order to do so, Radosuboff created a thesaurus. Due to the arrival of objects from Leipzig, the Museum started the collection’s digitisation earlier than other museums, but according to Radosuboff, in insufficient ways. He expanded the Museum’s current database GOS and started to define notions (Sachbegriff) and subject groups (Sachgruppen). Finding orientation in “a 1000m² storage area with several hundred cupboards of approximately eighty metres of shelves, stuffed with war repatriations” was a challenge, despite the inventory and database work, especially when it came to creating systematised ordering structures – imposing names, establishing hierarchies, creating meaning.

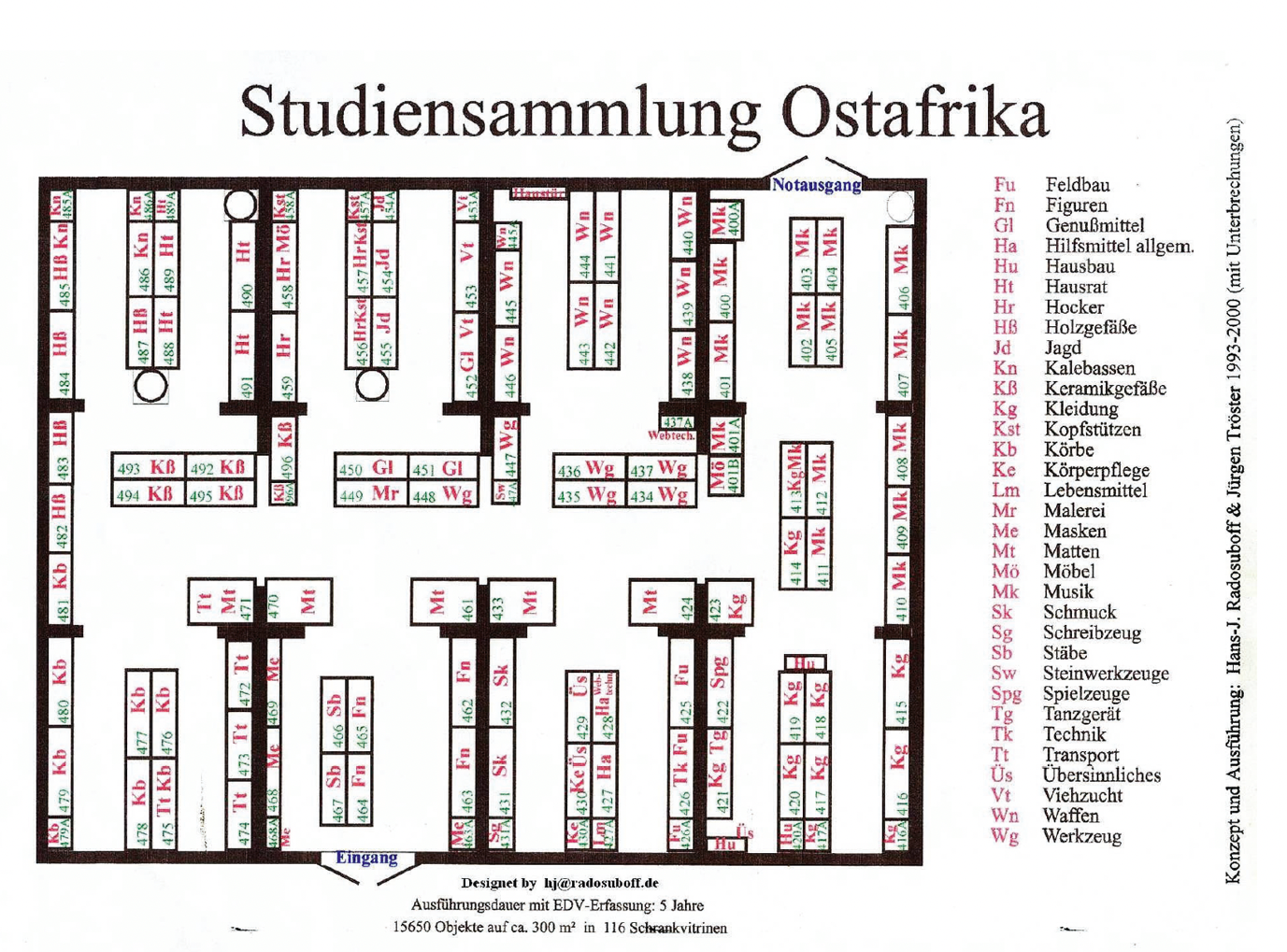

Fig 4 The “East Africa” storage, sorted by subject groups, schema drawn by Hans-Joachim Radosuboff.

“I had a lot of ideas in a short period of time. But then I realised that every single idea I have, I need to keep up 75,000 times”. With museum staff “dodging away when I mention the thesauraus”, Hans-Joachim Radosuboff consulted dictionaries, talked to different people, including his dentist („What is the difference between “medicine” (Medizin) and “drug” (Arznei)?“), in order to do justice to his assignment of creating order in the storage. This process came not without (self-)conflicting questions, such as when discussing the semantic field around “magic” (Zauberei), “bewitchment” (Hexerei), “religion”, “spirituality”, or the “extrasensory” (übersinnlich). His thesaurus would later be taken over by the entire Museum, becoming thus what Radosuboff described the “Museum’s database’s Mama, the Ur-Mama (great-mother)”.

Object love

The responsibility Radosuboff expressed towards making the collections accessible was paired with his expression of “object love”. Object love, as used by Sharon Macdonald referring to curatorial work, translates into a general commitment to the collection, a feeling of responsibility, honour, and the need to care for the objects (Macdonald 2002:65; see also Geoghegan and Hess 2015). Radosuboff attested to his particular relation to the objects through his personalised narrative and choice of metaphors and words. He referred to the objects as “my children”, or framed it as his duty “to protect” the collections. In 1996, he commented on the leaking roof, stating that “Sometimes, something swashed in the storage which would burden my soul.” To counteract “lakes of water” causing damage, he was forced to install internal gutters, going into buckets. Keeping the storage tidy, organised, and neat was for him a “matter of honour” (Ehrensache).

Care for the object thus also translated in a diversity of, sometimes improvised, practices. When walking around in storage with me, Hans-Joachim Radosuboff pointed to the different techniques he had invented to store the objects safely. In the context of what he described as a lack of budget, “I needed to have a lot of energy and ideas!” He always had a pen and paper lying beside his bed. “Sometimes I would wake up at 4 a.m. and would say to myself: ‘Ah, this is how I am going to do it!’ And I would write it down immediately.” For example, in order to fill hitherto empty storage cupboards, he asked all his friends to give him old cardboard tubes and clothes hangers from the drycleaner. He pushed his colleague, a wine drinker, to never throw away the cork. Wedges made out of cork would avoid putting objects directly on the shelves and would stabilise them.

“Kept” rather than “dead”

In scholarly writing, museum objects are often described as immobile, stable, and unchanging; as controlled, restricted, confined. For Hilke Doering and Stefan Hirschauer, conserving objects means that “the normal biography of a thing is decelerated, if not halted completely. Aging and decay are replaced by a fixing of the actual state, a kind of eternal youth” (Hirschauer and Doering 1997: 297). Samuel J. M. M Albertini describes the “museum effect” as “a phenomenon observed by museologists whereby an object is radically dislocated from its point of origin, wrenched from its context and rendered a frozen work of art in the surrounds of the museum” (Alberti 2007: 373). When I characterised the museum storage in similar terms as a “graveyard” for objects, portraying the objects as “dead” and “unactivated”, the storage manager strongly disagreed. He referred to the objects as not being “dead” but rather being “kept” – situating conservation as an active and resource-demanding part of museum work. This understanding of conservation work resonates with Laurajane Smith’s argument that heritage “doesn’t exist” but rather is “a cultural practice, involved in the construction and regulation of a range of values and understandings” – values that museums have been promoting as being universally applicable and valid (Smith 2006: 11).

One core conviction consists of heritage being “of the past, in the present, for the future”, implying for museum workers the obligation and responsibility to keep, in order to pass on (Harrison et al. 2020: 4). Heritage practices are thus geared towards “assembling, building and designing future worlds” (ibid.). But what kind of future? It is a particular kind of life that museum objects can be exposed to, as they are subject to rules and legal regulations. These basically deny the collections any other forms of life than museum life. This norm has been questioned in particular with regards to ethnographic collections, of which many objects have been persons, subjects, co-habitants before they were integrated into the museum infrastructures. The regulations limit the ways in which these subjects-turned-objects can be handled, researched, and displayed, and thus, restrict how they can circulate.4 Pioneering examples of engaging with the objects differing and shifting ontological status have been attributed more attention recently5, but what I call the paradigm of conservation still persists as the dominant norm in museums. For the largest parts of the collections, this means: Once a museum object, always a museum object.6 Hans-Joachim Radosuboff’s work with the collection contrasts the images of the stability and immobility of the collection, foregrounding rather the ongoing work that “keeping” objects consists of. These processes also entail that the objects themselves might have become dangerous for their surroundings: The products once used to protect the objects have turned the objects into artefacts that humans need protection from.

Entwesung and toxicity: from object to subject

In 2002, Hans-Joachim Radosuboff described in his diary (2021: 25) how :

“Suddenly, in this otherwise financially dwindling year, there is money to measure everywhere the deposits of toxicity (Altlasten an Giften) in the collection. And a number of things are identified. DDT, lindane, PCB, mercury, arsenic. They exist in very different quantities in the collection.”

Paralysing an object doesn’t only occur when taking it out of its original context where it might have ‘lived’ and imprisoning it behind glass or placing the object in anonymous storage. The killing also becomes physical and literal, by the museum’s attempt to erase everything living inside and around the objects to preserve it (Arndt 2021). The official German term for the practice of disinfecting is entwesen. In a literal translation, entwesen can be translated as “de-being”. The term can thus be understood as describing the attempt to erase anything living within the object. In practical terms, conserving means killing.7 Historically, the objects were literally poisoned by the application or injection of pesticides and heavy metal compounds. Even though this method was common in all Western museums, ethnological objects were especially vulnerable because they consist mainly of organic materials.

The scene depicted by Hans-Joachim Radosuboff captures the atmosphere in the Museum in 2001-2002, when after complaints from museum staff, an external company assessed the effects of the objects’ contamination. Based on random samples, the company analysed the quality of indoor air, the composition of dust, and the concentration of pesticides within selected objects. Blood samples of employees in frequent contact with objects were made (Radosuboff 2021:25). Research by the Ethnological Museum’s conservator Helene Tello suggests that two-thirds of the Museum’s collections are contaminated, and that the objects were treated “extensively and continuously” with heavy metal compounds and pesticides from very early on, some of them even in their place of production and collection (Tello 2006: 12). The analysis’ results confirmed that the health risk for museum employees was “relatively high” (ibid.: 67). The documentation and archival traces of the use of pesticides and heavy metal compounds are scarce, but guidelines for pest control date from as early as 1898 and 1924 (ibid.: 36–39). Tello’s research equally shows that the objects which were subject to relocation – such as those stored in Leipzig, and other temporary storage spaces during the Second World War – bear additional traces of treatment (ibid.: 44–47). Different materials represent different degrees of contamination and thus risk. Textiles, for example, are especially charged with chemicals, while metals are less apt to absorb them.

As a consequence of the poisonous vestiges, before entering the collections, visitors have been obliged to sign a document to confirm that they come at their own risk.8 Usually, the collections are kept within closed cupboards, reducing the degree of pesticides and heavy metals in the air. Once the cupboards are opened, however, a full-body suit with breathing mask and gloves is recommended for personal protection. Hans-Joachim Radosuboff, who had been in constant contact with the objects, spending his days in the storages and also eating there, was assigned a new, separate office. On a farewell card (2003), a former intern wished him good luck “I hope you will not be poisoned in the Museum at some point.“ (Radosuboff 2021: 38). Despite the results of this analysis, whether or not museum employees would protect themselves, and how, was also their personal decision, and many did not easily adopt the new protection in their daily routine. In his diary notes, Hans-Joachim Radosuboff commented on how he tried to circumvent the newly imposed rules (ibid.: 25). Conversing, he laughed, saying that “I didn’t die from it. If the DDT made me infertile, I wouldn’t know because I don’t want children anymore in any case.’” When I was working in the storage, the rooms felt charged. Headaches and nausea were recurrent after my visits.

Fig 5 and 6: The nitrogen tent, photograph: Marion Benoit.

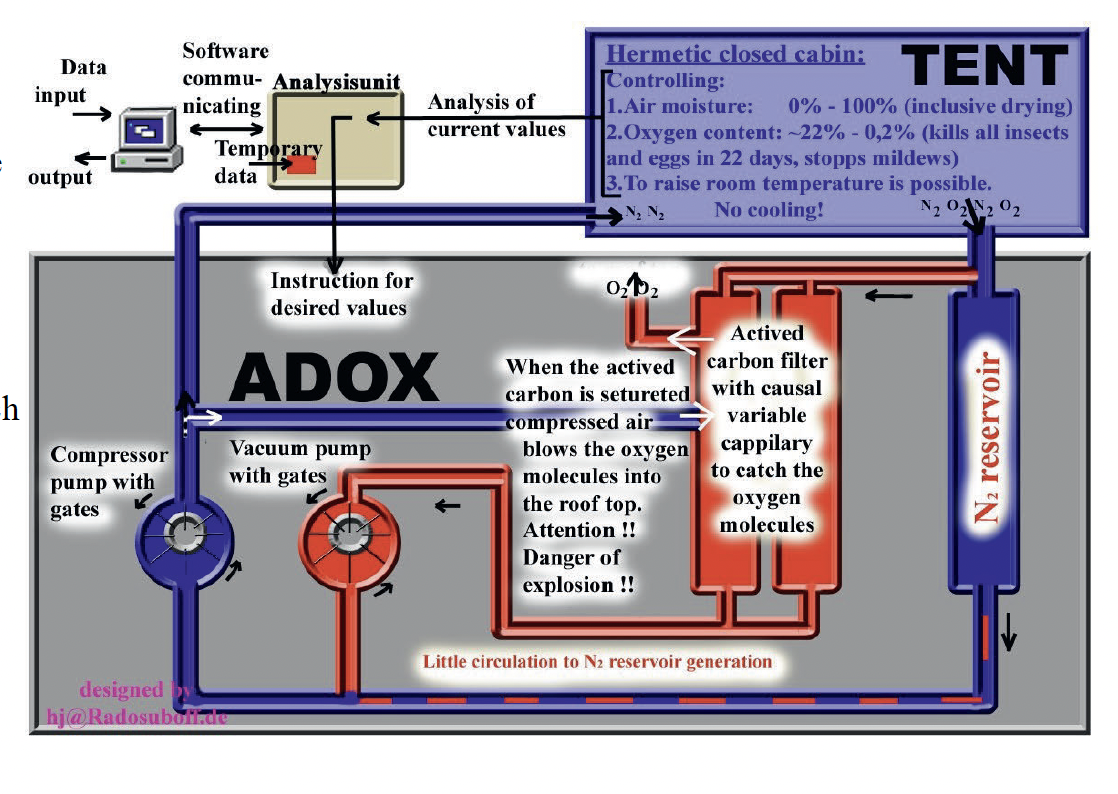

Fig 7: Diagramme drawn by Hans-Joachim Radosuboff for international guests

In 2004, Hans-Joachim Radosuboff writes in his diaries, the old disinfecting machine, working with gas (tetrachloroethylene), was destroyed (Radosuboff 2021: 32, 39). The machine had effects not only on the employees, but also on the objects treated. Radosuboff reports that a new machine is installed that attracts many professional visitors who want to understand how the nitrogen tent works.

This technique, subtracting oxygen, is still used today, alternatively to the method to freeze the objects. These procedures are part of what is framed as non-invasive Integrated Pest Management, IPM. In both places, ‘freezing chamber’ (Gefrierkammer) or the nitrogen tent, objects are isolated from their surroundings for some time, in order to eradicate those living beings which might alter their material stability. Given his enthusiasm and interest in technical innovation, Hans-Joachim Radosuboff observed the install of the new machine, “bombarding the technicians with questions”. Once installed, “the question arised: And now, who will operate the machine?” And he had found himself a “great extra job.” (Radosuboff 2021: 41).

Fig. 8 Hans-Joachim Radosuboff’s wagon with a red bucket containing camphor, photograph: Hans-Joachim Radosuboff.

There was a particular smell within the storage. It was the trace of a peculiar practice used by the storage manager that he had adopted from his predecessor. He had placed the chemical solid camphor in yoghurt cups in every single cupboard to protect the objects from infestation (Befall), an invasion of insects in a particular group of objects. Used historically as a pesticide, Radosuboff was convinced that camphor could protect the objects. “I mean, I felt it was successful, I did have very little infestation! But it was very much disliked by my colleagues. Well, it’s true, the smell, camphor, is an insult to the nose. But then people said it was harmful. But come on, this stuff is part of baby lotion!” Camphor was controversial amongst museum staff. Helene Tello states in her research that the use of camphor was already proven ineffective at the beginning of the 20th century. A lack of knowledge transmission, she argues, was a direct consequence of a lack of documenting the Museum’s own practices (Tello 2022: 232). The use of camphor is just one example of how treatments had not only an effect on those working with them, but also on the objects themselves.

“It is an undeniable fact that damage such as fading or changing of colours, yellowing of paper, black spots and/or blooming on works of art or in entire collections are residues of former treatments with pesticides. Hence, besides destruction, these pesticides must be considered an additional potential cause of damage by conservators in their daily work (Tello 2006: 136, see also Tello 2022: 195).”

The objects’ transformation of substance

In an essay on decay and transience, Joshua Pollard described the change of an object’s materiality as “the transformation of substance” (Pollard 2004). Whilst it might thus prevent or delay the processes of decay, the practice of Entwesung doesn’t keep the object stable, and fixed. The treated objects transform differently, but in equally substantial terms. Countering the ideas of the immortal and durable quality of objects, the observation of these processes allow the redefinition of their understanding. As such, ethnographies of processes of conservation, as the work of scholars such as Fernando Domínguez Rubio at New York’s MoMA or Tiziana N. Beltrame at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris shows, shed light on the way in which the works’ temporalities are constructed. By observing attempts to stabilise heritage in a material way, the very notions of the stable and perpetual are set in motion (Domínguez Rubio 2014; Beltrame 2017). Taking into consideration the transformative potential of the material, museum collections can be conceptualised “as collections of processes rather than as collections of ‘objects’”’ (Domínguez Rubio 2014).

As part of these processes, the substances turn the collections into agents by rendering them toxic. As Lotte Arndt poignantly writes, “[t]oxicity, as a relational category, articulates the artefact with its environment, and brings fixed classifications into movement” (Arndt 2022: 285). Through the continuous and seething presence of these compounds, the objects disturb the regulated procedure and supposedly sterile environment of the museum. Some of the objects contrasted with what Fernando Domínguez Rubio depicts as “docile objects”: “artworks that diligently occupy their designated ‘object-positions’ and comply with the set of tasks and functions that have been entrusted to”. On the contrary, these objects were unruly insofar as they were leaving marks, as if exhaling their venomous breath (Domínguez Rubio 2014). The residues of chemicals inside objects have been leaking out on the objects’ surface, and have materialised in the form of a shiny dust. They left traces, described by museum staff as objects “blooming out” (ausblühen). Sometimes white crystals, similar to ice, appeared.

To remove the chemicals, visible or not, conservators “aspirated” (absaugen) objects, a job described as lengthy and unsatisfying. “It’s not like cleaning the living room. You aspirate those tiny objects for hours, the machine is extremely loud and you most probably won’t see the result of your work. It’s also unsatisfying because it’s a superficial treatment. The objects are thoroughly contaminated and the remnants of treatments will continue to leak.”9 The removal of pesticides and heavy metal, however, could only ever be superficial because they were now completely part of the object’s physical and material constitution. Whereas “wet methods” for cleaning the objects would remove dust and soiling from the objects’ surfaces it would have “little impact on the matrix of artefacts” (Tello and Unger 2010: 37). Traces of the residues also marked exhibition furniture such as plinths, caused by evaporation (Ausdünstungen), which usually consisted of fat that originated in the objects’ patina.10 Besides these evaporations, there was a diversity of different forms of dust in the Museum. This dust would appear also inside glass showcases, even if the objects were perfectly isolated by the glass, as if the object was sweating – a particular dust that Hans-Joachim Radosuboff was good at taking away in the Museum’s showcases.

Fig. 9: Hans-Joachim Radosuboff and a colleague cleaning the show cases from the inside, photograph: Hans-Joachim Radosuboff.

Dust is a matter, as Tiziana N. Beltrame describes, which ties elements and entities in the museum together. It allows the insects’ presence in storage and exhibition areas to be mapped: it is a supplier of food for the insects and fungi to nourish themselves from, but it is also a sign of the objects’ physical histories and treatments, providing another layer of traces about where they have been and what has been done to them (Beltrame 2016).

Objects as amalgams of their histories

Hans-Joachim Radosuboff’s narrative and the history of the “Africa” storage show that objects become inseparable from those who manipulate them, as well as from the infrastructures, technologies, digital and physical environments, invisible substances which conserve but transform them. Museum objects are physically, and thus irreversibly, an amalgam of their different histories (Etienne 2013, 2018). The making and returning things into museum objects has had material, lasting, and irreversible consequences on the objects’ physical and symbolic constitution and identity.

With a view to the virulent discussions on the rearticulation of ethnological collections and archives and their actual and potential restitution, the text raises questions in relation to the paradigms in which the object will be and can be thought and worked with. Central here is the question whether or not the paradigm of conservation will continue to be privileged in the treatment and definition of museum collections. This includes interrogations on whether the museum’s primary goal should be to keep things for future generations, or rather if its aim should be to use its collections for present ones. Do these options exclude each other? And if not, how can the paradigm of conservation be made compatible with the objects’ former uses and roles, and thus with the option to “resocialise and resemantise”, in “ecologies” that are “necessarily plural”, as Bénédicte Savoy’s and Felwine Sarr’s suggest (Sarr and Savoy 2018: 27)?

-

I refer to the Ethnological Museum here with Museum with a capital M, and to museums as organisations in lowercase letters. ↩

-

Hans-Joachim Radosuboff deposited Museographie 1 (2019) and Museographie 2 (2021) at the Museum’s library. They are consultable there. If I do not refer to other sources, the direct quotations stem from the conversation with Hans-Joachim Radosuboff on 15 January 2015. I translated the original German to the English, including also text references that are German in their original form. ↩

-

Quotation from Hans-Joachim Radosuboff’s 1991 diaries, http://www.radosuboff.de/em/1991/afro_jahr1991.html, consulted 20 December 2017. ↩

-

The work of the curator and cultural historian Clémentine Deliss has been central with regards to claiming access and the opening up of collections. She put this request in action in particular when she directed Frankfurt’s Weltkulturenmuseum (2010-2015), see for example Deliss 2020. ↩

-

See for example John Moses in this issue. ↩

-

The recent claims for restitution problematise this paradigm. However, the collection’s legal status complicates changing their use and status significantly, such as attempts to “deaccession” and “decollect”. To put it bluntly in Jennie Morgan’s, Harald Fredheim’s and Sharon Macdonald’s words when describing museum profusion: It is not easy for museums “to get rid” of things (2020: 161). ↩

-

This museum mechanism becomes even more obvious in collections of Natural History. See for example, Tahani Nadim on the shifts between live and death at the Natural History Museum Berlin (Nadim 2022: 167). ↩

-

The document confirmed that ‘[the c]ontamination with PCP (pentachlorphenol), lindane and DDT (dichlorodiphenyl-trichloroethane) as well as the elements arsenic and mercury has been determined’ (Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz 2017). ↩

-

Conversation with a museum storage manager, 30 October 2013, fieldnotes from 26 November 2013. ↩

-

Fieldnotes from 19 October 2015. ↩

BibliographieBibliography +

Alberti, Samuel J. M. M. 2007. “The Museum Affect: Visiting Collections of Anatomy and Natural History.” In Science in the Marketplace. Nineteenth-Century Sites and Experiences, edited by Aileen Fyfe and Bernard Lightman, 371–403. Chicago ; London: The University of Chicago Press.

Arndt, Lotte, ed. 2021. Les survivances toxiques des collections coloniale/ The toxic afterlives of colonial collections. Troubles dans les collections, n°2. ———. 2022. “Poisonous Heritage: Chemical Conservation, Monitored Collections, and the Threshold of Ethnological Museums.” Museum and Society 20 (2): 282–301. https://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v20i2.4031.

Beltrame, Tiziana Nicoletta. 2016. “A Matter of Dust. From Infrastructure to Infra-Thin in Museum Maintenance.” Conference presentation, Barcelona, « Before/After/Beyond Breakdown: Exploring Regimes of Maintenance », 31.8.2016-3.9.2016. ———. 2017. “L’insecte à l’œuvre. De La Muséographie Au Bruit de Fond Biologique Des Collections.” Revue Techniques & Cultures 68 (2): 162–77.

Bloch, Werner. 2019. “Felwine Sarr: ‘Geschehen ist fast nichts.’” Die Zeit, July 24, 2019, sec. Kultur. https://www.zeit.de/2019/31/felwine-sarr-raubkunst-kolonialismus-museen-europa/komplettansicht.

Deliss, Clémentine. 2020. “The Metabolic Museum.”, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

Domínguez Rubio, Fernando. 2014. “Preserving the Unpreservable: Docile and Unruly Objects at MoMA.” Theory and Society 43 (6): 617–45.

Etienne, Noémie. 2013. “Objets en devenir et devenirs objet”, Retour d’y voir, revue du Musée d’art moderne et contemporain (MAMCO), Genève ; pp. 318-335.

Etienne, Noémie. 2018. “When Things do Talk (in Storage). Materiality and Agency between Contact and Conflict Zones”, dans Johannes Grave, Christian Holm, Valérie Köbi, Caroline van Eck (dir.), The Agency of Displays. Objects, Framing and Parerga, Dresden, Sandstein; pp. 165-177.

Feest, Christian F. 1991. “Coming Home At Last: Reunification and Repatriation in Germany.” Museum Anthropology 15 (2): 31–32. https://doi.org/10.1525/mua.1991.15.2.31.

Geoghegan, Hilary, and Alison Hess. 2015. “Object-Love at the Science Museum: Cultural Geographies of Museum Storerooms.” Cultural Geographies 22 (3): 445–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474014539247.

Harrison, Rodney, Caitlin DeSilvey, Cornelius Holtorf, and Sharon Macdonald. 2020. “‘For Ever, for Everyone …’.” In Heritage Futures. Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices, 3–19. London: UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787356009.

Hirschauer, Stefan, and Hilke Doering. 1997. “Die Biographie Der Dinge. Eine Ethnologie musealer Repräsentation.” In Die Befremdung der eigenen Kultur: Zur ethnographischen Herausforderung soziologischer Empirie, edited by Stefan Hirschauer and Klaus Amann, 1st ed., 267–97. Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft : Stw. – Berlin : Suhrkamp, 1968- 1318. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Macdonald, Sharon. 2002. Behind the Scenes at the Science Museum. Oxford; New York: Berg.

Macdonald, Sharon, Jennie Morgan, and Harald Fredheim. 2020. « Too many things to keep for the future? In Heritage Futures. Comparative Approaches to Natural and Cultural Heritage Practices, 155-168. London: UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787356009.

Morse, Nuala, Bethany Rex, and Sarah Harvey Richardson. 2018. “Special Issue Editorial: Methodologies for Researching the Museum as Organization.” Museum and Society 16 (2): 112–23.

Nadim, Tahani. 2022. “Doubling the Troubles” In Awkward Archives. Ethnographic Drafts for a Modular Curriculum, edited by Margareta von Oswald and Jonas Tinius. Berlin, Dakar, Milan: Archive Books, pp. 166-175.

Pollard, Joshua. 2004. “The Art of Decay and the Transformation of Substance.” In Substance, Memory, Display: Archaeology and Art, edited by Colin Renfrew, Chris Gosden, and Elizabeth DeMarrais, 47–62. McDonald Institute. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/390293/.

Sarr, Felwine, and Bénédicte Savoy. 2018. “Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle.” http://restitutionreport2018.com/.

Schorch, Philipp. 2018. “Two Germanies: Ethnographic Museums, (Post)Colonial Exhibitions, and the ‘Cold Odyssey’ of Pacific Objects between East and West.” In Pacific Presences – Volume 2. Oceanic Art and European Museums, edited by Edited by Lucie Carreau, Alison Clark, Alana Jelinek, Erna Lilje, and Nicholas Thomas, 171–85. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

Smith, Laurajane. 2006. “The Discourse of Heritage.” In Uses of Heritage, Illustrated edition, 11–43. London: ROUTLEDGE.

Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz. 2017. “Instructions for Visitors to the Study Collections (Storage Area) of the Ethnological Museum Berlin.”

Tello, Helene. 2006. “Investigations on Super Fluid Extraction (SFE) with Carbon Dioxide on Ethnological Mterials and Objects Contaminated with Pesticides.” Fachhochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin. https://lhiai.gbv.de/DB=2/SET=3/TTL=1/SHW?FRST=9.

Tello, Helene. 2022. Schädlingsbekämpfung in Museen. Methoden und Wirkstoffe, am Beispiel des Ethnologischen Museums Berlin 1887-1936. 2022. Köln: Böhlau Verlag.

Tello, Helene, and Achim Unger. 2010. “Liquid and Supercritical Carbon Dioxide as a Cleaning and Decontamination Agent for Ethnographic Materials and Objects.” In Pesticide Mitigation in Museum Collections: Science in Conservation Proceedings from the MCI Workshop Series, edited by A. Elena Charola and Robert J. Koestler, 35–50. Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation 1. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.