Based on discussions of the Picha collective, board member Filip De Boeck outlines the intentions for the coming Biennale.

Toxicity will be the central theme of the seventh Lubumbashi Biennale, which will take place in the fall of 2022. The biennale has been co-founded by artist Sammy Baloji in 2008 under the name “Rencontres Picha”, and offers a vibrant public platform to local and international artists and cultural actors alike (see Mitter 2019 on the previous Biennale). This year, six invited curators will be working alongside the collective and the Ateliers Picha (the latter under the artistic direction of Lucrezia Cippitelli) to address ‘toxicity’ as an urgent concern.

Obviously composed of two concepts, that of the ‘toxic’ and that of the ‘city’, the Biennale considers reflecting upon the link between contemporary life in the postcolonial urban setting of Lubumbashi and more widely in the urban Global South, and the impact of a number of industrial, economic, ecological, social and cultural processes that have historically contributed, for better and for worse, to the shape and dynamics of urban life in this and other parts of the world today. In this sense, Picha understands ‘toxic’ in reference to a wide – and historically multi-layered – variety of events, discourses, and practices.

Toxicity, first of all, might refer to the impact of colonialist modernization and the colonial and postcolonial histories of rise and decline that accompanied its processes of industrialization. These were shaped most strongly in the Copperbelt, of which the city of Lubumbashi, Congo’s second largest city, and the former capital of ore-rich Katanga1, are an inextricable part (see for example Jewsiewicki, Dibwe and Giordano 2010). Famously, the uranium used for the production of the atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki was extracted there, but the toxic fallout of Katanga’s extractive economies reached much further and produced much deeper ecological consequences on a local and global scale. In recent years, new histories of extraction have generated new toxicities, as highlighted in artistic projects such as ON-TRADE-OFF, a long term project that was initiated by Picha and Enough Room for Space in 2018 (Arndt/Gueye 2020) and is carried by a dozen artists and writers in the DRC, Europe and Australia, in an attempt to trace the raw material lithium and its crucial role in the global transition towards a ‘green’ and fossil fuel free economy. As part of this project, Jean Katambayi Mukendi, in close collaboration with Daddy Tshikaya, Sammy Baloji, Alain Nsenga and Rosa Spaliviero, produced a copy of the notorious Tesla Model X made of recycled copper wires, in order to draw attention to the economic inequalities within Congolese social classes, which he believes will grow even more through the environmental impact of the so-called “green revolution” and capitalist mining industry.

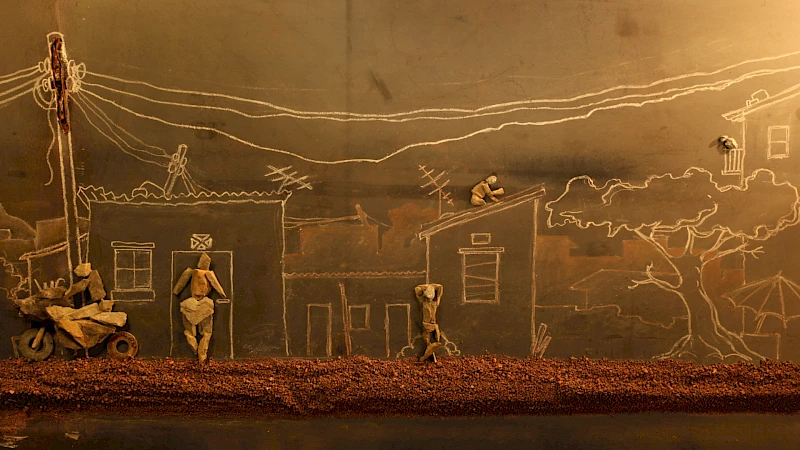

All these well-documented regional histories of toxicity and pollution of soil, water and air, in large parts of rural and urban Southeast Congo, continue to impact and degrade landscapes and livelihoods, turning this corner of the world into what Achille Mbembe famously called a ‘Zero World’ (Mbembe 2014), a world destroyed by colonization and the use of the technological machine. It is this extractive destruction that is highlighted in recent film projects such as Machini, a stop-motion movie on mining by Tétshim and Frank Mukunday (2019), as well as in Sammy Baloji’s 2016 video-installation Pungulume, showing how heavy machinery progressively eats up the territory of the Sanga population. Similarly, recent literary and more academic work also focused on the impact of industrial mining in the Congolese part of the Copperbelt (see for example De Boeck and Baloji 2016; Makori forthcoming; Sinzo Anzaa 2015).

Frank Mukunday and Tétshim : Machini, 2019, 10’, Filmstill

These historical layers also make Katanga an intrinsic part of African and more global anthropocenic tales. Katanga may thus be seen as a possible ‘ground-zero’ of the Capitalocene in which ‘extractive economies of subjective life and the earth under colonialism and slavery’ (Yusoff 2018) may be told and established, unearthing the toxic quality of colonial history itself, and revealing the impact on ‘the nervous condition’ (Hunt 2016) of the Congolese (post)colonial state and the world order at large.

But toxicity does not only reference Katanga, and by extension the African continent, as a dumping ground for global toxic waste and industrial detritus (cf. Gupta and Hecht 2017; Livingston 2012). Toxicityalso gestures to other ‘matter out of place’: plastic bags, for example, or other kinds of ‘dirt’ (Newell 2020). In recent years, the ecological consequences of plastics and other toxic circuits impacting Congo’s urban environments were addressed in artistic performances by, amongst others, Julie Djikey, Eddy Ekete and other artists belonging to the Kinact street art performance collective based in Kinshasa (see also Malaquais 2019 for a presentation of this Kinois collective).

Moreover, ‘dirt’ not only refers to material rubble, but also to mental debris. Both can be found in the afterlife of imperialist and capitalist destruction (see Gordillo 2014), or in the legacy of infrastructural ruinations that perpetuate the colonial presence in the present (Lagae 2004; Stoler 2016). Simultaneously, this out-of-place matter also allows for a reflection on the impact of these various pasts, offering a tangible possibility, from these imperial aftermaths, to imagine ‘potential histories’ (Azoulay 2019) and futures for places and people.

Next to out-of-place matter, toxicity also refers to ‘people out of place’, the ‘human waste’ of populations that have been rendered superfluous, displaced or relocated through equally toxic and violent histories of occupation and subjugation, exploitation and extraction, or ethnic division and strife. Thinking about and with toxicity therefore allows to open up a space of reflection about the meaning of autochthony, identity, sociality and self in the current moment. To think with toxicity as ‘matter out of place’ and ‘people out of place’ (whether individuals or collectivities that are considered toxic and therefore have to be discarded, abandoned, dilapidated and annihilated –examples are easily encountered in the Congolese urban setting: street children, (child) witches, ethnic Others…), begs for a reflection about who has a ‘right to the city’. It offers the opportunity to ask critical questions about the venomous qualities of the city’s social architectures and infrastructures, its poisonous promiscuities, its ‘toxic discursive complexes’ (Laudati & Mertens 2019) and the constant acts of piracy that accompany the spatial and social proximities necessary to survive and exist in the ‘pirate town’ (Simone 2006) that the city often turns out to be. As such toxicity is at the heart of the urban social condition, a condition that can also be addressed by means of the figure of the Virus, one of toxicity’s many incarnations (see Povinelli 2020). Beyond the obvious reference to viruses like AIDS, Ebola, and more recently COVID, and their impact on (urban) living in the DRC (for example by resuscitating colonial segregationist lines between Ville and Cité in the 2020 COVID lockdown of Gombe, Kinshasa), the Virus might also refer to various other kinds of parasitic and infectious activities. As Michel Serres teaches us, the unwanted guest that the parasite is, generates noise and interference, makes social flows static, takes without giving and weakens without killing. And as such, it is both the atom of a relation and the production of a change in this relation (Serres 1997).

This means that reflecting on the toxic as virus, and as poison, pirate, and parasite also invites us to think about mutation and transformation and opens up the prospect of imagining and generating alternative orders. As Danny Hoffman (2017) states: “To inhabit a toxic landscape, one must become mutant, learn to grow new and impossible organs”. If, for many, the present is toxic, its poison might also be used to set in motion processes of metamorphosis, and to inform acts of healing, somewhat along the lines of the therapeutic logic of homeopathic medicine, which uses the very substance that causes a disease to fight it. This is a very common principle in many of Central Africa’s therapeutic traditions, in which the harm or evil that a witch inflicts upon his/her victim, is captured and sent back to its source by the healer.2

The theme of toxicity, then, offers a starting point for a critical elaboration and consciousness of oneself and one’s natural, social and cultural environment, “as a product of the historical processes to date, which has deposited in you an infinity of traces, without leaving an inventory.” (Gramsci 1971:324). By focusing on the theme of toxicity, the Lubumbashi Biennale endeavors to open up a critical space of artistic engagement and reflection to start exploring the possible shapes such ‘an inventory of traces’ might take, in the hope that such a compilation will also tell us something more about the possible futures to envision from here on.

Since 2010, Frank Mukunday and Tétshim have been producing self-taught animated films. Starting from the practice of drawing (Tétshim) and video (Frank), their duo founded the studio « Crayon de cuivre » in Lubumbashi. After two experimental films “Cailloux” and “Kukinga”, Machini is their first film made in professional production conditions.

BibliographieBibliography +

Lotte Arndt and Oulimata Gueye, On-Trade-Off. Countering Extractivism by Transnational Artist’s Collaborations, 2020. https://commodityfrontiers.files.wordpress.com/2020/10/commodity-fronters-1-fall-2020.pdf

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History. Unlearning Imperialism. London / New York: Verso, 2019.

Filip de Boeck and Sammy Baloji, Suturing the City. Living Together in Congo’s Urban Worlds. London: Autograph ABP, 2016.

Gaston Gordillo, Rubble. The Afterlife of Destruction. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2014.

Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks. London: Lawrence and Wisehart, 1971.

Pamila Gupta and Gabrielle Hecht, « Toxicity, Waste, Detritus: An Introduction » Somatosphere. Science, Medicine, and Anthropology. 2017. [http://somatosphere.net/2017/toxicity-waste-detritus-an-introduction.html/]

Danny Hoffmann, « Toxicity ». Somatosphere. Science, Medicine, and Anthropology, 2017, https://somatosphere.net/2017/toxicity.html/

Nancy Rose Hunt, A Nervous State. Violence, Remedies, and Reverie in Colonial Congo. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Bogumil Jewsiewicki, Donatien Dibwe dia Mwembu and Rosario Giordano, Lubumbashi 1910-2010. Mémoire d’une ville industrielle / Ukumbusho wa mukini wa komponi. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2010.

Johan Lagae, « Colonial Encounters and Conflicting Memories. Shared Colonial Heritage in the Belgian Congo », Journal of Architecture, 2004, 9 (2): pp. 173-197.

Ann Laudati and Charlotte Mertens, « Resources and Rape: Congo’s (Toxic) Discursive Complex ». African Studies Review, 2019, no. 62 (4): pp. 57-82.

Julie Livingston, Improvising Medicine. An African Oncology Ward in an Emerging Cancer Epidemic. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

Dominique Malaquais (ed.), Kinshasa Chroniques, Montreuil, Les editions de l’œil, 2019.

Timothy Mwangeka Makori, Rich Soils, Empty Hands: Artisanal Mines, Governance and Historical Generations in the Congo Copperbelt, à paraître.

Achille Mbembe, « The Zero World. Materials and the Machine ». In: Sammy Baloji, Mémoire / Kolwezi. Brussels: Africalia, 2014.

Siddhartha Mitter, « On the Frontier, the Lubumbashi Biennial Makes Art From Obstacles ». New York Times, December 13, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/13/arts/design/lubumbashi-biennial.html

Stephanie Newell, Histories of Dirt. Media and Urban Life in Colonial and Postcolonial Lagos. Durham / London: Duke University Press, 2020.

Elisabeth Povinelli, « The Virus: Figure and Infrastructure », 2020, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/sick-architecture/352870/the-virus-figure-and-infrastructure/

Michel Serres, Le Parasite. Paris: Hachette, 1997.

Sinzo Anzaa, Généalogie d’une banalité. La Roque-d’Anthéron: Vents d’ailleurs, 2015.

Ann Laura Stoler, Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times. Durham / London: Duke University Press, 2016.

Catherine Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes Or None. University of Minnesota Press, 2018.