In memory of Dominique Malaquais

I am part of the generation of artists who introduced performance art into the contemporary scene in Kinshasa. When I was studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kinshasa at the end of the 1990s, we were essentially taught in a very classical way – painting, sculpture, drawing…. But we were rebellious and besides the disciplines we were taught at the academy, we developed our own practices. We started to make performances for ourselves. We were young, we collected scraps from the street, and we played, and performed. The movement grew gradually. In fact, we were already performing as teenagers, but not necessarily naming it “performance”. There were many moments where we were acting out situations by taking turns, always in the public space.

Mega Mingiedi Tunga during his performance Kesho, Lubumbashi Biennale, 2019.

We ended up bringing this practice to the art academy. The professors mostly met our initiatives with contempt, and did not take us seriously. This has changed today: performance art is established in the art field, including in Congo. That said, there is still no official school for our practices. But they are beginning to be recognized, locally and internationally, and are beginning to be valued. Especially in Kinshasa, performative forms have come a long way. They have been solidified and enriched by exchanges with different traditions, with performers from elsewhere, and in the context of festivals.

Today, highlights such as [Kinact,](http://Hyperlien http:) initiated by Eddy Ekete in 2015, bring together every two years many performers and a curious public. In fact, performative practices have existed for a long time in Congo, and contemporary artists continue to reinvent them in the current context. In order for these forms to continue, and to be transformed in relation to societal changes, the question of transmission is essential in my eyes.

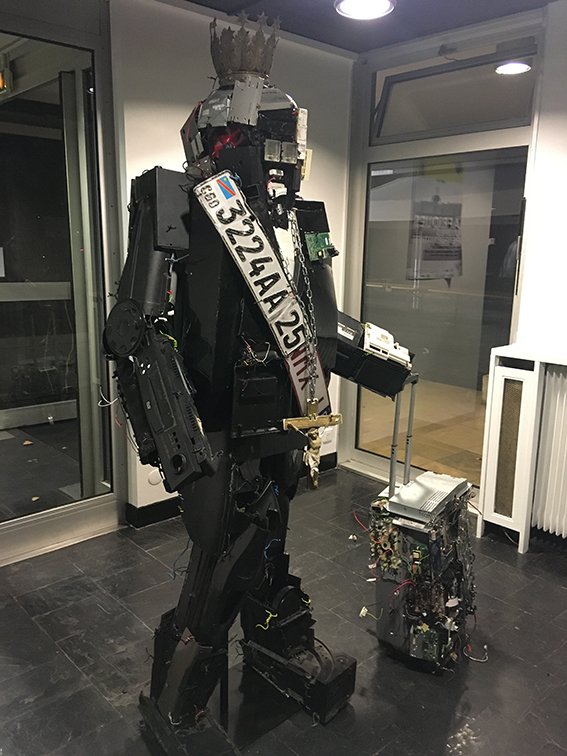

Today, we are seen by the younger generations: I do not have a position at the Beaux Arts de Kinshasa, which maintains a very classical teaching, but students from the art school and university come to consult me. They strive to meet contemporary artists to learn in direct conversation with us – we are no longer on the periphery of creation. Performances are now frequently visible in the public space and the costumes are beginning to be shown in galleries. At the central entrance of the Cité des arts in Paris, during the Utopies performatives (curated by Dominique Malaquais and Julie Peghini, September 2021), was exposed the Lumumba costume made by Precy Numbi. This creates an important visibility !

Precy Numbi: Lumumba. Brussels. Costume in recycled materials, 2020. Here, exhibited at Cité des arts, Paris, September 2021

Kesho at the Biennale of Lubumbashi, 2019

The year 2019 brought me doubly to Lubumbashi: I was invited to the Biennale to show my work, and before that, the Ateliers Picha gave me carte blanche to animate a workshop for ten days with young performers from Lubumbashi. So I elaborated my performance Kesho with this group, in a process where they accompanied me in the conception, the creation and then the performance in the streets of Lubumbashi.

In this workshop participated a group of young people who were very motivated, but had very little training in performance. We discussed a lot about what performative forms can include, their relation to the public space, the role of costumes… which allowed us to problematize what we were going to put into action, to better understand the stakes. Then, we continued the workshop in a practical form, to set up my performance Kesho, which means « the future » in Swahili. The title points to taking charge of the future – no one is going to think it for us! It’s about saying: « You have the right to believe in it, and to confront it based on your desires! »

Co-construction of a globe by the participants of the workshop conducted by Mega Mingiedi Tunga in preparation for the performance Kesho, Lubumbashi 2019.

My work consisted in artistically accompanying the group. The participants had a lot of desires but they needed someone to encourage them, to show them the possibilities, the steps, and to guide them in their choices. Further it was a question of experiencing the act of performing, and receiving feedback: a performative situation is a powerful moment; you enter another universe, you are caught up in it and it can be overwhelming. The encounter with the city involves many unpredictable situations, and you have to react spontaneously, invent, interact! It can become very intense for the performers. But the presence of the public also allows us to get a feedback, a criticism, and to understand what we are doing. It is necessary to think about our gestures carefully beforehand, in order not to generate violent situations.

Lubumbashi is a very important economic hub, with a multitude of stories and ways of telling them. It happens that the art scene, especially around Picha, has been configured mainly around photography, video… It lives up to its name (“picha” means “image” in Swahili). Bringing our performance practices from Kinshasa to Lubumbashi allows us to establish bridges and exchanges, and facilitates the appropriation of this form by the artists of Lubumbashi and to work with it in relation to their reality, the present in Katanga.

Performance art has been demonized by artists who are adept at more traditional art forms: it has been criticized for being too simple, for imitating theater, for being a European import, for corrupting morals… Whereas performance art speaks to our life situations here on the continent! Moreover, in African traditions, gestures and shared collectively significant movements have always existed.

Performance happens when people are gathering, gestures are executed, others watch, and exchange. The performances speak about political questions, about the city, about collective life. This allows people to grow, to better understand political and social issues, to discuss it together, to adjust their judgments, and to take a stand. We intervene in the fundamental questions of society; we talk about the economy, pollution, gendered violence, perpetrated in the context of war, but also more intimate questions! This involvement is palpable in the exchanges with the public. The audiences have an open mind, they look, they listen. They come out of curiosity. People see something happening that they don’t know about and they are intrigued. They come to see, to observe, to discover new forms, to read and interpret the performances in a way that is often very rich and informed, because they share the same social experience.

Unfortunately, there are not many Congolese authors who write about our work. I am among the Congolese artists who initiated a lot in terms of performance in Kinshasa. But we did not write, we did not name our actions. Now, it is mostly European authors who put words to our practices. And this changes considerably what is at stake. I fear that this situation causes misunderstandings, especially if the authors know little about the context and offer equivocal readings.

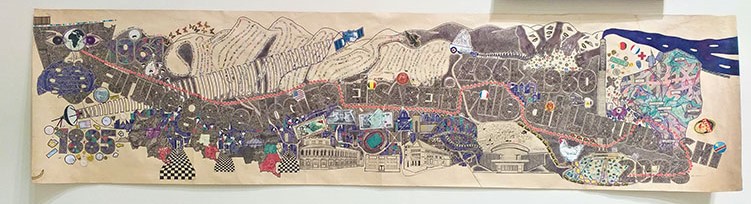

Mega Mingiedi Tunga : Elisabethville, known as Lubumbashi, 332 cm x 83 cm, Mixed media, drawing on 250g khaki paper, Collage, ballpoint pen, 2019.

If I imagine the biennial in ten years, it will have considerably broadened the practices that will be shown and would put even more emphasis on the local scene. The RDC is vast – there are many artists! Picha is already an important showcase and also does a lot of work locally. It is precisely this connection that needs to be developed and deepened. Ateliers Picha are thinking along these lines: the duration of the workshops led by artists in residence should be extended, and this should be financially supported in the longer term to ensure viability for the artists and for the participants. Beyond a ten-day initiation, such as I set up in 2019, it would be a question of accompanying the participants in the development of their own projects. It requires a real individual and collective follow-up in the long term and could be ensured by artists during periods of one month or two, during the year preceding the biennial. And then, the biennial would bring together invited artists and projects developed during the workshops. Exchanges, international meetings, visibility and transmission would then be intertwined.

Toxicities

The theme of the next biennial, ToxiCity, seems to me very relevant: the world is polluted, and it is particularly so in this part of the Congo. The history of mining has left its lasting vestiges. In Lubumbashi, in Kolwezi, the chemical smell is perceptible everywhere. The mining giant Gécamines has determined the history of the city for more than a century, still operates today, and leaves deep traces in the lives of the inhabitants, in the environment, at all levels. In the mining areas, toxicity is omnipresent. Today, the city keeps growing rapidly, and new constructions are often established on very polluted grounds.

But we can also bring the idea of toxicity to international artistic structures: the role of the North for Congolese creation today is ambiguous. The market remains largely off the ground: our creations are read, bought and consumed in Europe, Africa benefits very little from them. If we consider that our arts are also a wealth, not only minerals, to see them leaving so massively to the North is painful. My family, my relatives never see my work! This situation creates misunderstandings, suspicions… If it is easier to see the works of a Congolese artist at the AfricaMuseum in Tervuren, where you have to pay twelve euro for the ticket, than in Kinshasa, Goma or Lubumbashi, relations have not changed much in the last fifty years!

The funds should follow: most international funding is project-based and not long-term. This creates a situation in which, as artists on the African continent, we are often the losers. No matter how much we travel, we don’t end up with viable structures. The problem has two sides – there is a market in Europe, but that often means moving away from the Congolese context, losing what makes sense in our work: while in the DRC, there is almost no support from institutions, almost no funding and official recognition. People buy Chinese posters more easily than a popular painting or an artist’s drawing – for economic reasons, but also because contemporary creation is too little identified, recognized and supported.

To carry out a work of performance often requires resisting manifold social pressures, prejudices and rejections, including from one’s own family. Not everyone understands the work of artists and this can lead to a lot of mistrust, especially if it happens abroad. We have to be aware that our practices are not taken for granted; they require a long and consequent investment, with important and often heavy consequences in our lives.

We always forget when we see an artwork the considerable labor and effort that makes it possible! To maintain an artist’s practice when living in the DRC, when one has family obligations, requires a constant abnegation. We are in a country where economic and social realities make life very complex. People have to carry a lot of responsibility. We are constantly fighting, without ever knowing if it will last and for how long.

For the future, I think that transmission is a crucial issue. My commitment is to continue to « make », to multiply the workshops that allow us to put collaborations into practice. Young artists need to be accompanied and supervised and this requires the involvement of the generation that precedes them. Every day, I welcome young artists in Kinshasa and encourage them to continue their work. To transmit is for me a pleasure, a commitment, a value, it is there that things make sense and where I see what I can give, but the question is if it is economically viable. One should not have to choose between a context that allows one to live decently, and one’s artistic work, in connection with our society!