Vanessa Agard-Jones, « Bodies in the System », Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, 2013 Vol. 17, Issue 3, pp. pp. 182-192.

Stacy Alaimo, Exposed. Environmental Politics and Pleasures in Posthuman Times, University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Antonia Alampi, Deadly Affairs, Exhibition and catalogue, Kunsthal Extracity, cahiers # 5, Antwerp, 2019.

Lotte Arndt, « Étendre l’espace de la vie. Réagencements narratifs au seuil des collections muséales dans le travail de Kapwani Kiwanga », in Elisabeth Piskernik, Gabrielle Camuset (eds) : Travelling Narratives, Rabat, Le Cube, octobre 2021, pp. 35-62.

Lotte Arndt, « La riposte du toxique », dans Sandra Delacourt (dir.), Hiérarchies du Vivant, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, à paraître.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Unlearning Imperialism. Potential History, London, Verso, 2019.

Anna Bednik, Extractivisme, Lyon, Le passager clandestin, 2019.

Tiziana Nicoletta Beltrame, « Œuvres et temporalités. (Dé-)construire la pérennité au musée », dans Chloé Andrieu, Sophie Houdart (dir.), La composition du temps ? Prédictions, événements, narrations historiques, actes du colloque de la MAE, Paris, de Boccard, 2018, pp. 65-76.

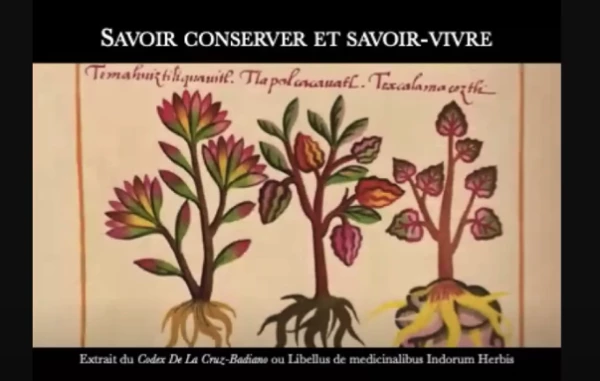

Samir Boumediene, La colonisation du savoir. Une histoire des plantes médicinales du « Nouveau Monde » (1492-1750), Vaulx-en-Velin, Les éditions du monde à faire, 2016.

Tina Campt, Listening to Images, London/New York, Duke University Press, 2017.

Chris Caple, Conservation Skills. Judgement, Method and Decision Making, London, Routledge, 2000.

Mel Y. Chen, Animacies. Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect, Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2012.

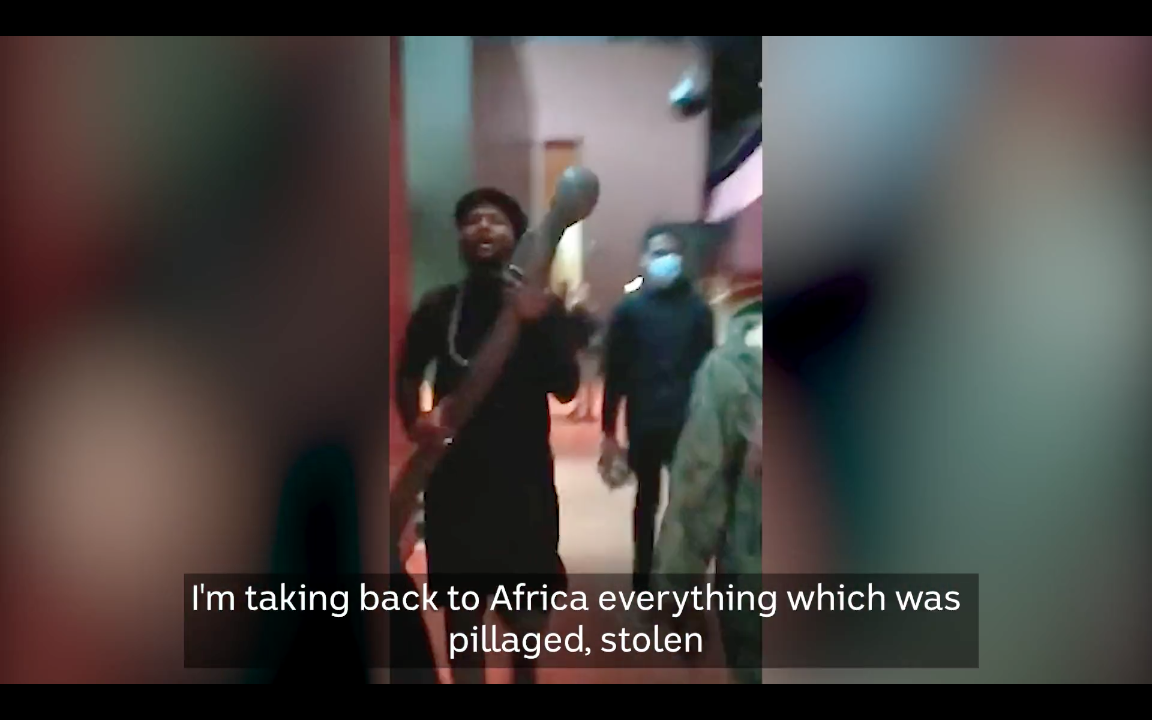

Allan Clarke, Lisa McGregor, « The man snatching Africa’s ‘stolen’ treasures from the museums of Europe, » abc net, 8 Sep 2021, last seen 26, September 2021.

Jean-Paul Delahaye, L’exception consolante. Un grain de pauvre dans la machine, Paris, La librairie du Labyrinthe, 2021.

Clémentine Deliss, The Metabolic Museum, Hatje & Cantz, 2020.

Souleymane Bachir Diagne, « Musée des mutants », Esprit, 2020/7, pp. 103 – 111.

David Dibosa, « Exhibiting Embarrassment », 2021, https://www.harun-farocki-institut.org/de/2021/03/01/exhibiting-embarrassment-journal-of-visual-culture-hafi-48/.

Fernando Dominguez Rubio, « On the Discrepancy between Objects and Things. An Ecological Approach », Journal of Material Culture, 2016, 21(1), pp. 59-86.

Malcom Ferdinand, Ecologie décoloniale. Penser l’écologie depuis le monde caribéen, Paris, Seuil, 2019.

Jana Haeckel (ed.), Everything Passes Except the Past. Decolonizing Ethnographic Museums, Film Archives, and Public Space, Brussels, London, Sternberg Press 2021.

Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone. Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives, Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2017.

Avery Gordon, Ghostly Matters. Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Durham, N.C., Duke University Press, 2016.

Tim Ingoldt, Making. Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture, Londres, Routledge, 2013.

Noémie Étienne, « When Things Do Talk (in Storage). Materiality and Agency between Contact and Conflict Zones », in Johannes Grave, Christiane Holm, Valerie Kobi (dir.), The Agency of Display: Objects, Framings and Parerga, Sandstein Verlag, 2018

Sumaya Kassim, « The Museum Will not Be Decolonized », 2017, https://mediadiversified.org/2017/11/15/the-museum-will-not-be-decolonised/.

Bruno Latour, Nous n’avons jamais été modernes, Paris, La Découverte, 1991.

Elisa Liepsch, Julian Warner, Matthias Pees (dir.), Allianzen. Kritische Praxis an weißen Institutionen, Bielefeld, transkript, 2018.

Roland May, Denis Guillemard (dir.), « La conservation préventive. Une démarche évolutive (1990-2010) », _Techn_é, n° 34, 2011, pp. 3-94.

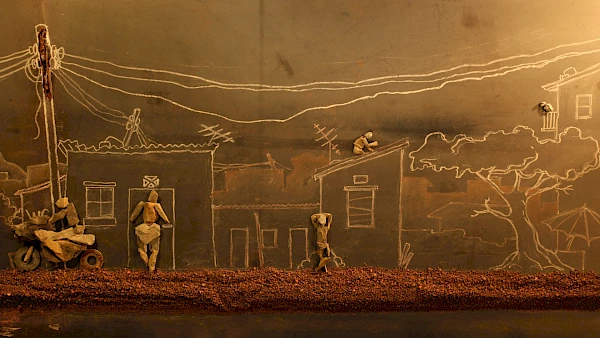

Achille Mbembe, « The Zero World. Materials and the Machine », dans Sammy Baloji, Mémoire / Kolwezi, Bruxelles, Africalia, 2014.

Nancy Odegaard, Alyce Sandongei (dir.), Old Poisons, New Problems. A Museum resource for managing contaminated cultural materials, Walnut Creek, AltaMira Press, 2005.

Nielsen, May-Brith Ohman, « Bugs and Borders in historical studies. Boundaries of History », Scandinavian Academic Press, 2015, pp. 109 – 183.

John Peffer, “Africa’s Diasporas of Images”, Third Text, 2005, 19, (4), pp. 339–355.

David Pinninger, Integrated Pest Management for Cultural Heritage, Londres, Archetype Publications, 2015.

Elisabeth Povinelli, Geontologies. A requiem to late liberalism, Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2016.

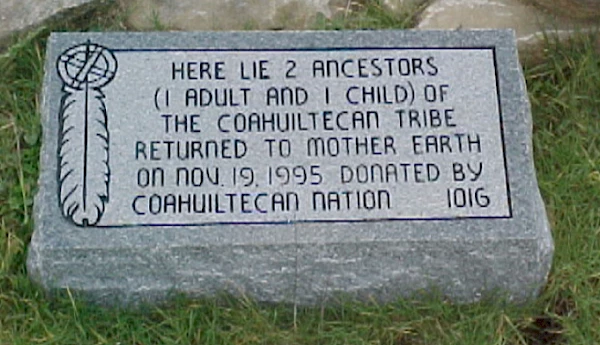

Felwine Sarr, Bénédicte Savoy, Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle, novembre 2018.

Nanette Snoep, “De la conservation à la conversation”, Multitudes, 78, n. 1, 2020, pp. 198 – 202.

Françoise Vergès, « Racial Capitalocene. Is the anthropocene racial ? », 2017, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3376-racial-capitalocene

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Nils Bubandt, Elaine Gan, and Heather Anne Swanson (dir.), Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2017.