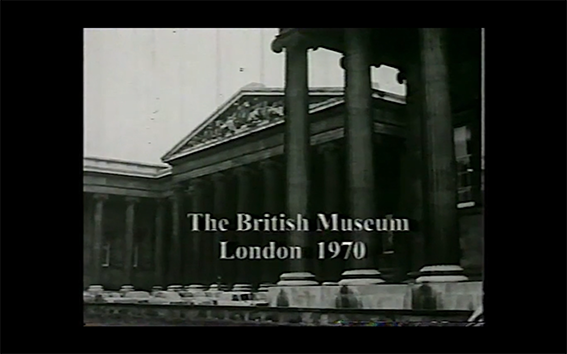

In the course of this interview carried out on 24 August 2022, Ghanaian filmmaker Nii Kwate Owoo recounts the making and the many lives of his iconic film ‘You Hide Me’. Made in 1970 as his final piece at the London International Film School where he was then enrolled, it has now gained new momentum through the restitution debate. In the film shot in the basement of the British Museum, the filmmaker powerfully challenges the monopoly of the North, which not only unilaterally grants itself the ownership of the objects forcibly extracted from the African continent, but also the authority of the expertise around these objects. A fierce Pan-Africanist activist and intellectual, Nii Kwate Owoo is one of the founding members of the Pan-African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI), of which he has been a member since 1969, and is now actively engaged in restitution campaigns in Ghana.

Much about the multiple resonances of the film remains to be explored. On the one hand, its distribution needs to be mapped more finely. For example, the crucial information that Nii Kwate Owoo reports here about a copy of the film’s purchase by Eyo Ekpo, the renowned archaeologist and director of the Nigeria Federal Department of Antiquities, who was at the time actively engaged in efforts to return Nigerian property (Malaquais & Vincent 2020; Bodenstein 2020 and 2022; Savoy 2022) makes it possible to link these claims beyond/across sole national strategies and bilateral talks between the former imperial center and the former colony On the other hand, ‘You Hide Me’ should also be closely reconnected to the history of its now lost first part, which the filmmaker is currently actively seeking to recover in the British archives. In it, Nii Kwate focused notably on the practices of three African artists: Ibrahim El Salahi (born 1930), Uzo Egonu (1931-1996), Dumile Feni (1942-1991). Even though we can only imagine it for now, it importantly foregrounded voices and living artistic gestures beyond the objects silenced in the museums’ storerooms.

Marian Nur Goni: I have read that at the time of the making of ‘You Hide Me’ (1970), you were highly impressed by books such as The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) and Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice (1968). I would be interested to know more about the cultural and political spirit you found yourself immersed in at the time? How did these readings or specific events prepare you for making this film?

Nii Kwate Owoo: During my student days at the London International Film School in the UK around the late Sixties, I developed a keen interest in social issues relating to the Black minority struggle against racism and exploitation in the country, primarily because the oppression and exploitation of natural resources in Africa by our former colonial “masters” were my own issues as well. So I became attached to a group of community activists in London, who called themselves ‘Black Unity and Freedom Party’ (BUFP). Around the same period, I was also very much involved with students and activists from Southern Africa. These students were schooling or working in the UK as exiles from Zimbabwe, South Africa and Namibia. Their struggle against oppression and apartheid was embraced and supported by the BUFP and other local activists from the Caribbean who were either born in England or were living there at the time.

The Black Unity and Freedom Party was a research-oriented organization made up of a very lively intellectually and politically motivated study groups which included Black lawyers. Their objectives were to organize the youth and workers in how to combat and deal with racism at the workplace, including police harassment in their communities. We were also influenced by what was going on in the US: Black Power and the Black Panther movement. Historically, three outstanding Black activists provided the ignition that lit the “fuse” of the Black nationalist movement in the US, which spread far and wide across the Atlantic into every nook and cranny of the Black Diaspora. First, it began when out of the blue, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, a book by Alex Haley, suddenly burst onto the scene of an already politically charged atmosphere, becoming a best seller. Then with Eldrige Cleaver, a renowned and outspoken African-American militant and political activist, whose book Soul On Ice was “unleashed” into an already highly-charged atmosphere of Black struggle against police brutality, gun violence and unprovoked attacks on unarmed Black community activists in America. Cleaver became an icon overnight for all of us in those days, particularly when his book was first published and released in England. All of us bought copies, avidly read and discussed it in our study groups. It was followed by Solidad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson (1970), a most vivid, powerful and amazing account of the evolution of the political consciousness of an incarcerated Black prisoner from the inside. These three books made an enormous impact on the political development of my generation at that time.

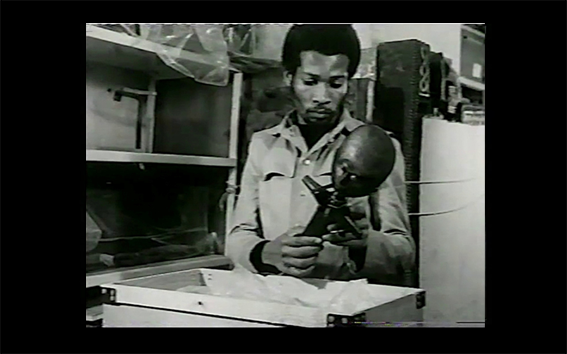

MNG: In this issue we seek to also understand how taking action on colonial violent legacies affect the people who start those processes. You are the filmmaker and the producer of this film, but you also appear in it opening boxes, opening drawers, looking and manipulating objects. Can you describe this experience, which was also I guess an emotional one, from the point of view of those emotions and the young man you were then? What did the touch of those artefacts provoke?

Nii Kwate Owoo: African art and African history were my favorite subjects during my high school days in Ghana; I won all the school prizes in art. I even considered the idea of pursuing a degree course in art with the intention of becoming an art teacher. However, when I came to England, it suddenly dawned on me that the art of film and cinema was, rather, the most powerful medium of communication. So when I left the film school, I decided to delve into investigative research into African art history. The best place for me to look for that kind of information was the British Museum. I went there to browse through their various art exhibits from various countries around the world. I was quite struck by the fact that the Africa section was limited in terms of scope and size compared to their elaborate exhibits on Egyptian, Greek, Roman and Assyrian objects, which were the most prominent and major exhibits on display. It suddenly dawned on me that I could start exploring the possibility of telling a story about the African artefacts that were in the glass and wooden cases. It was just a wild guess, so I made some enquiries as to how to obtain permission to record these artefacts. I was directed to their information department. I didn’t expect any positive outcome, but I went in there and made an appointment to meet the curator of the Africa section of the museum.

Still from ‘You Hide Me’ (1970).

Before meeting him, I decided that I had to change my dress code, because, as a Black activist, I used to wear black clothes as my standard dress code wherever I went: it was our standard militant attire. So I went to the West End of London and rented a three-piece suit from a company that rents out suits and costumes to theaters. On the day of my appointment, when I entered the curator’s office, he became excited. He got up from his desk and walked over towards me, arms outstretched in a goodwill gesture to welcome me with a friendly handshake. This was a good sign, I thought to myself. We sat down and he introduced himself, telling me how he knew Africa extremely well because he had worked as a former colonial district officer in Nigeria for the British. His name was William Fagg.

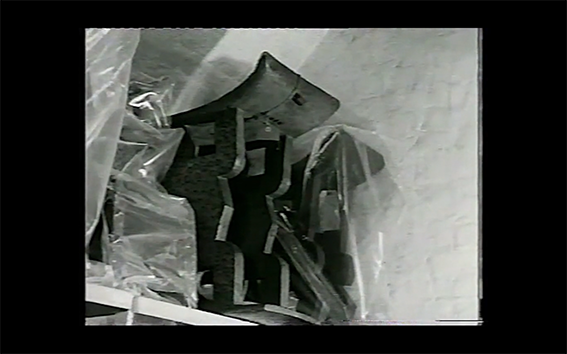

I informed him about how really excited and impressed I was with what I had seen in the Africa section of the museum. He quickly drew my attention to the fact that what was in the exhibition hall represented only two percent of what they had in their Africa collections. So I said that I would like, with his permission, to arrange to make a short documentary for posterity, to pay special homage to people like him for allowing me to be the first African ever to be given an opportunity to have a glimpse into our past… That was my strategy! Long story short: he led me to a door behind his office desk, opened it and led me down an iron spiral staircase which descended about fifty feet below the ground floor of his office until we finally reached a basement of what seemed like a vast network of shelves and corridors jam-packed with wooden boxes and plastic bags of all shapes and sizes crammed together. Before my very eyes lay an amazing collection of various African artefacts, some of which were life-size statues standing between interconnected vaults divided by long corridors linking each vault to the next one.

I was shocked, visibly overwhelmed and shaken by what I discovered down there. First, there was this strange and almost mystical aroma emanating from every section of the basement, where hundreds and thousands of rare and sacred artefacts as far as the eye could see were being stored. These stolen and looted ancient artefacts including numerous bronze and other metal statues, big and small, had been hidden and locked up for centuries like a war booty of a conquering colonial army. I became emotional and had to control myself. It was so surreal and unbelievable that it felt as if I had just stepped out of a time machine: One minute I was in the present and the next minute somewhere in 15th-century Africa. In fact I was really traumatized.

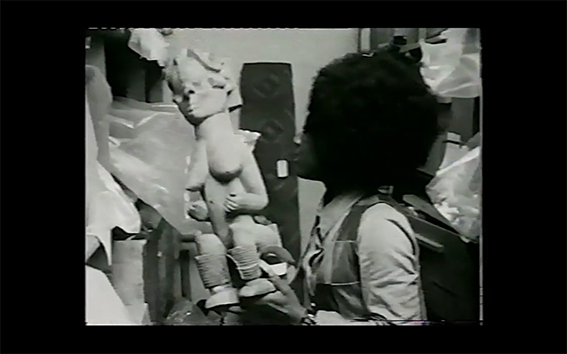

Stills from ‘You Hide Me’ (1970).

Finally, we came to an arrangement which resulted in me signing a contract with him stipulating that I would be allowed to bring a team of only four production personnel, including myself. The contract also stipulated that my team would be allowed to shoot the film in one day, from 9 am to 5 pm. The entire production cost me about 500 pounds, but I had to pay half of it to the British Museum authorities. When I asked why I had to pay so much money to them, they said that it was to cover the fees of fifteen museum security officers who would monitor us and watch every move we made as they guided us through all the different sections of the basement. They would be there to ensure that we didn’t “steal” any of the artefacts they had looted and stolen from Africa…

I had to quickly raise the cash for my production expenses from friends and sympathizers in the UK, before I was able to go back to the British Museum. I was accompanied by Ms. Margaret Prah, a Ghanaian colleague who is a lawyer. We were so amazed by what we encountered within that short period of time that we were allowed down there that sometimes we had to put the camera aside in order to explore, feel and touch these sacred artefacts. Subjectively speaking, it was phenomenal and an amazing experience as we began to bond with these artworks. Never ever in my wildest imagination could I have imagined that our ancestors would have created such incredible and refined works of art. Precisely because none of them were ever depicted or mentioned in any of the colonial history textbooks we read in school. Anyway we had to rush our way through the different vaults in the basement to record a few items here and there as fast as we could to save time.

Still from ‘You Hide Me’ (1970).

At this juncture, I would like to pay special tribute to a British progressive, leftist group called the “Cinema Action Film Collective”, founded and led by a German called Schlacke Lamche and his British wife Ann Lamche, who unfortunately passed away about two weeks ago. They were so moved by my boldness and political activism and were also fascinated by the fact that I had been able to outwit the museum authorities, to penetrate the basement of the British Museum, where no British television network had ever been allowed to film. They provided me with editing facilities free of charge. That was what actually made it possible for the film to be cut and to be finalized, it was a major support, for which I will be forever grateful.

MNG: Tell me about the writing of the powerful commentary of the film. The film script is a charge against how the North has continually deprived the African continent of its own cultural resources, first by pillaging its art and secondly by ‘discovering’ it, and how material culture has been involved in justification for colonization, and then preservation: the strong argument you make about the “experts”.

Nii Kwate Owoo: I was spiritually fired with anger after my descent into the basement by the fact that all these rare and sacred artefacts revealed an extremely high level of cultural development and enlightenment of our ancestors and their civilizations. These sacred objects were now being hidden in wooden boxes and plastic bags, after they had been violently looted and stolen from our ancestors by colonial expeditionary forces. I was fired up as I made my way through the vaults of the basement when suddenly, in my mind’s eye, I experienced a kind of “memory recall” of the wound, the pain, the trauma and dislocation of our ancestors; it went through me like a flash. I felt their presence as if they were touching my spirit and felt like they were appointing me as an “ancestral messenger”, tasked with a mission to go out into the world to reveal and expose the truth of what happened to them, where they are and why they were being hidden and incarcerated. That experience crystallized in me and gave birth to the title of the film ‘You Hide Me’ right there in the basement of the British Museum, and how the message should be crafted and delivered in the film. The rest is now history. When the late renowned and celebrated Ghanaian traditional drummer and musician Kofi Ghanaba saw the film for the first time forty years ago, he said to me, “Now look here Nii Kwate, with all due respect, you have to change the title of the film, to “You Can’t Hide Me”. I agreed with him! Indeed, that’s the message of the film.

Stills from ‘You Hide Me’ (1970).

MNG: How was the film received at the time?

Nii Kwate Owoo: In 1971, I went to the Africa Center in London to appeal to the director of the center to sponsor the premiere of the film there. The director at the time was a British woman who very warmly accepted my request and took on the mission of organizing the premiere. She invited over two hundred people, including academics from all the major universities in England, including professors in African art and archeology. As I couldn’t raise the funds to secure a married print of the film from the commercial film laboratories in London, it was projected through a special projector that shows the final edited image and sound together but separately on two special reels. I invited the British Museum authorities and offered them the front seat in the hall where the film was scheduled to be screened, but they politely declined and chose rather to sit at the back of the hall closer to the main entrance. As soon as the film started and they heard the commentary, they quickly disappeared from the hall… The film was very well received because the invited audience erupted into huge spontaneous applause and a standing ovation as I made my way towards the screen with congratulations and chants of “Bravo! Bravo!! Bravo!!!” from the audience. When it ended, I was emotionally overwhelmed and close to tears. People in the audience eagerly donated cash, while others made pledges of support to help me to place an order for the married print from the labs.

With a married print finally in my hands, I tried to get it distributed in England, but it was impossible! The distribution companies were not interested in the film. So I had to show the film on one or two occasions to students in universities and at SOAS (the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London). Then finally in 1971, I decided to take the film back to Ghana because I felt that the reception and the historical importance of the film would be well received and appreciated in Ghana and Africa.

Still from ‘You Hide Me’ (1970).

On my arrival in Ghana, I tried to get the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC) interested in the film, but alas, I was very disappointed by the negative reaction of the then managing director of the station at that time. Without even seeing the film, his attitude was that this kind of film would create problems between the Ghanaian government and the British government because of the existing cordial relationship between our two countries. However, I insisted that, as a Ghanaian, I had a right to have my work shown on national television too, so after putting a bit of pressure on him, he finally decided to organize a special screening of the film at the Goethe Institute, the German Cultural Center in Accra. He then appointed one of his producers to watch and vet the film to determine whether it had the requisite quality standard required for Ghana television. On the day set aside for the screening, his representative showed up, but to his surprise, I had also organized and invited all the young filmmakers and producers in the Ghana film and television industry to come to the premiere. The film was twenty minutes long at that time. As the audience began to applaud the film, the GBC representative quietly slipped away and left the room without saying anything to me. Among the invited guests was a journalist from the Daily Graphic, the leading national daily in the country. The next morning to my surprise, there was a long editorial in the Graphic newspaper supporting the film. I went back to the broadcasting station director only to be informed by him that the film was too controversial. “We cannot have this kind of subversive material here on our screen” he said, and that his advice to me was that I should leave the country immediately in my own interest because otherwise it could create some security problems for myself.

So the film was banned. However, unknown to me, news about the banning of the film in Ghana had reached the weekly West Africa Magazine published in England, which wrote a very interesting article.1 That is what made the film known for the first time: the ban actually made the film even more controversial!

MNG: Let me go back for a minute because I read that, after the London premiere, you sold many copies of the film.2 It would be really interesting to draw a cartography of the film’s distribution at the time. Who saw it, where? What response did it elicit?

Nii Kwate Owoo: Well, the first order for the film came from Dr Ekpo Eyo, the curator of the Nigerian museum in Lagos, who had read about it in the West Africa Magazine, which was a well publicized political and social magazine read by prominent African politicians and intellectuals in Africa.3 A few orders for a print came up but there weren’t that many actually. However, there was a lot of interest in screening the film, particularly in the US. That is when I realized that the US was probably my best option for the distribution of the film. Indeed, in 1972, I decided to relocate to the US and there I met an organization called the ‘Philadelphia Filmmakers Workshop’. They were very instrumental in helping me to distribute the film, because they prepared an impressive information brochure, which they mailed to different organizations and institutions. I am really grateful to Lamar Williams, an African-American filmmaker who was the founder of the organization; he played a major role in packaging the film. As a result of this brochure, schools, community colleges, universities and libraries in America invited me to come and screen the film. So I did a screening tour, and I got paid for the presentations and for teaching. It was in the US that the film actually was well distributed in the sense of being screened.

Information brochure for the film ‘You hide Me’, Nii Kwate Owoo, 1970, Philadelphia Filmmakers Workshop.

MNG: What were the reactions to the film on the part of these African-Americans students, who were perhaps also engaged in the Black movements?

Nii Kwate Owoo: People were angry! In those days, I was really fired by people’s reaction to the film. People were talking about the fact that we should organize a movement to campaign for the return of our stolen artefacts, and in those days, you know, the issue of restitution was not even on the table or in the air for discussion. Actually, it surprised a lot of people that the film was bold and uncompromising in its demand for the return of the artworks to the rightful owners in Africa.

Nevertheless, it drew people’s attention to museums in the US, because it never “clicked” in their minds that these rare objects that they saw in museums and private collections were looted or stolen from Africa.

On the whole it was a very successful trip because, unknown to me, the late Prof. J.H. Nketia, the then director of the Institute of African studies at the University of Ghana, was also visiting the US at that time. He had heard about the film and wanted to watch it, but he was in California while I was on the East coast, so we missed each other. When I went back to Ghana in 1974, I was introduced to him by Professor Efua Sutherland, a famous novelist and playwright. I happened to have a copy of the film because I always carried it everywhere I went for preview screenings. After finally viewing the film at the Department of African Studies, he asked me what my plans were and the way forward. I said: “Prof, I’m out there in England, hustling to survive, looking for a job as a filmmaker” because in those days it was not possible to earn a living as an independent filmmaker in the UK. He said: “Okay, when you get back to London, go to the office of the University of Ghana there and inform the director that I have asked you to apply for a position as a Research Fellow at my Institute because I want you to set up a Film Department.” Wow, I was so happy and totally overwhelmed because it was such a dramatic and unexpected turning point in my life! I expressed my heartfelt gratitude to him and quickly caught the next available flight from Accra to London.

So, finally, I was given a job and the task of setting up a film unit at the Institute of African Studies in the University of Ghana, called the Media Research Unit. The aims and objectives of my unit were to interact and collaborate with all the research fellows working in the different disciplines of African history, society, culture and music. I introduced the idea of disseminating their research findings through educational documentary films as a more vivid option instead of just relying on manuscripts and publications

MNG: I didn’t realize before that this film had such a major importance in your own life!

Nii Kwate Owoo: Indeed, it opened up tremendous opportunities. Because from there on, I went on to develop so many ideas and also to work on other productions. At the moment, I am trying to raise funding for a five-part docu-drama series on the history of the “Asante Empire of Gold” because I have shot so much material during my tenure as the Head of the Media Research Unit of the Institute of African Studies at the University of Ghana (1978-2004); I was recording and archiving stuff all the time. At one stage, I was able to raise enough money to buy my own Betacam video camera, but I didn’t have the editing facilities. So I was just recording and archiving all my footage. Currently, I have over 300 hours of material representing forty-five years of my work. I am now trying to digitize and capture them on external drives, then I can start telling more stories.

MNG: Looking at your filmography as a whole, it becomes apparent how African history and its narration is a thread running through your films and projects.

Nii Kwate Owoo: Absolutely. My attitude towards African history is critical thinking. One shouldn’t gather information just for its own sake, but one should delve deeper behind the information and analyze it critically. What are its origins, how did things become the way they are today? There are loads of history books and publications about Africa that are one-sided and not critical or analytical. So in the final analysis, you have to actually do your own independent investigation.

‘You Hide Me’ was not the only film I’ve made, but it was a turning point in my development as a filmmaker. I became aware of the power of the moving image; I came to the conclusion that there are two forms of consumption in human society and history. First we consume food through the mouth in order to release nutrients for our body to grow. So if you put rubbish into your system, rubbish will come out. As they say, “Garbage in, garbage out”. The second form is audiovisual consumption. We absorb information through our eyes and our ears. It enters our brains and undergoes a digestive process to become an opinion. Therefore, the end product of any audio-visual opinion is so critical to the factual representation or the distortion of the reality and history of any given society or people.

MNG: We have spoken about the trajectory of the film in the Seventies. I recently saw that ‘You Hide Me’ is part of the latest Isaac Julien art film, ‘Once Again… (Statues Never Die)’ (2022). Since the restitution debate has gained fresh momentum, the film has also taken on a new life.

Nii Kwate Owoo: Yes, Isaac Julien, the Black British filmmaker, is using a clip from my film in his museum project [at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia]. In fact in 2020, George Floyd’s assassination in the US became another turning point for my film. My son who lives in the US called me and said: “Hey Dad, there’s a film festival in Philadelphia, and they want ‘You Hide Me’.” The film was screened during the festival but, because it was fifty years old, it was not in competition. However, my son told me that the audience gave the film a standing ovation. Apparently, one of the organizers of the Paris Short Film Festival who was in the audience asked for my contact details. They got in touch with me and said they would like to showcase the film at their forthcoming festival. So I quickly dispatched a French subtitled version of the film to them. I was, however, surprised to hear that it was going to be in competition with films from five other countries. Boom! The next thing I heard was that the film had been awarded the first prize for Best Documentary Film in their Short Film category. I was like: “Wow!!! Coming fifty years after I shot the film?” It was a massive turning point that boosted the fortunes and reputation of my film beyond my wildest imagination. The Paris award galvanized the film and it went viral. I was getting calls from all over the world. The Paris film award has contributed enormously to drawing my film into the middle of the growing movement and debate on restitution. “You are the first camera to go down into the basement of the Africa section of the British Museum” – that’s what William Fagg told me – and to expose for the first time ever the artefacts that were looted and stolen from Africa. That’s what makes ‘You Hide Me’ a unique film.

The UNESCO representative in Ghana has also been very supportive of the film by organizing a special Zoom conference with me and other stakeholders in the country. I must also mention June Givanni from the Pan African Cinema Archive in London, who was in fact the first to organize a series of four webinars – ‘You Hide Me’ in 2020 – 50 Years On – soon after the Paris award, which also contributed enormously to making the film even more widely-known. Quite recently, the art historian Bénédicte Savoy included the film as one of the chapters of her latest book, Africa’s Struggle For Its Art.4

MNG: The last time we spoke, exactly one year ago, you mentioned AFROTEAM (Association for Restitution and Repatriation of African Artefacts in British, European and American Museums), an independent organization of which you are one of the founding members. What is going on now?

Nii Kwate Owoo: My mission now is to disseminate the film in all the major indigenous languages in Ghana first, for our local language television stations. UNESCO has pledged to support my organization to do the translations. After which I will go beyond Ghana, to spread the message of the film to other parts of Africa, beginning with a Yoruba version, an Igbo version, a Zulu version, etc. So ‘You Hide Me’ is going to take a walk around Africa! We need to sensitize our people on the ground because, if the commentary remains in English, it will not come down to the grassroots level, for people in the rural areas to watch it on TVs and participate the debate, because local language TV stations have programmes which allow for discussions.

The Ghana Ministry of Culture and the Creative Arts and the government have now supported the formation of a pressure group called the ‘Ghana Focal Group for the Restitution and Repatriation of Artefacts’, which is meant to organize a coordinated nationwide campaign involving the media and different civil society organizations all over the country. I am part of the Focal Group as a filmmaker with my own organization, Efiri Tete Communications. The Nigerians have done it and are getting interesting positive results from certain European countries, including Germany, who have started returning rare and sacred Benin artefacts among others from different museums back to Nigeria. Ghana is now about getting ready to launch its own campaign using my film ‘You Hide Me’ to target the British authorities and the British museum, as well as other museums in Europe and America, to return our artefacts back to their rightful owners. It will be a national campaign with a national orientation. So that is the framework within which I am operating now: to involve the ordinary masses and not just the elite.

-

A review of the film, “Plastic Bags and Glass Cases”, was published in the 26 March 1971 edition, pp. 332-333. It begins as follows: « Word has slowly been getting around of a remarkable short film made by a Ghanaian cineaste, James Nee-Owoo ». ↩

-

See the article “You Hide Me” by James Leahi in Vertigo n. 2, 1993 [online]. ↩

-

Ekpo Eyo served as the director of Nigeria Federal Department of Antiquities from 1968 to 1979. See Dominique Malaquais and Cédric Vincent, “Replicate This! Into the FESTAC Loop”, in Eva Barois de Caevel, Koyo Kouoh, Mika Hayashi Ebbesen, Ugochukwu Smooth C. Nzewi (dirs.), On Art History in Africa, Berlin, Motto et Raw Material Company, Dakar, 2020, pp. 31-47. [Also published in English under the title « Three takes and a mask » in Chimurenga (dir.), Festac 77, Londres, Afterall Books/Koenig Books, 2019]. ↩

-

Africa’s Struggle for Its Art: History of a Postcolonial Defeat, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2022, pp. 11-15 (chapter ‘1971’). ↩