Introduction

Ali Shreteh’s1 deep interest in cultural heritage and museums has led him to establish a family museum in their ancestral home located in Al Mazra’ al-Qibliya, near Ramallah. Despite their financial limitations, he took the initiative to partially renovate the house to showcase their family’s collection. In an interview the authors conducted with him via WhatsApp in October 2023, Ali expressed his passion by stating that « the museum is no longer a private collection; it is a shared space, a collective space. » Ali Shreteh’s family museum illustrates agentic spatiotemporality, one of the most intriguing examples of how subjects can assert their agency in the shadow of the Palestinian Museum at Birziet University (Cobbing, 2016, p. 155).

If the Palestinian Museum, a Swiss-registered non-governmental association with a branch in Palestine that opened in 2016 in the West Bank, can be considered as a “space of critique, resistance and decoloniality in the convoluted colonial context of Post-Oslo Palestine” (Toukan, 2018, p. 18), an anticipation of a [quasi]-state-to-come (De Cesari, 2019), a space of sumud (steadfastness) (Burke, 2020) or it exemplifies an “Alter-Native conception of self-determination”; as one of the many ongoing experiments with alternative sovereignty (Abu-Lughod, 2020, p. 23), what benefits can a family-focused museum approach offer in addressing the everyday challenges faced by local communities? If state-funded museums are usually located in urban metropoles and subscribe to universalised approaches to museum practice (Mataga et al., 2022), what spatiality and regime of values do family-based museums embrace? What memory do they claim to remember? What histories, written and oral, do they present? What materiality do they exhibit in assembling their family museums? In answering these questions, this article explores how families’ commitment to protecting and managing cultural heritage can turn their houses into museums, and the museums into new spatiotemporal spaces.

The point of departure in answering these questions in this article is a (self-) reflection on families’ approaches to converting traditional houses in Palestine into local museums that are located outside the realm of the PNA and NGOs. To aid the analysis, three case studies have been presented of Palestinian families converting traditional houses into local museums in villages in the West Bank. The author’s own family house is among the examples. Utilising diverse research methods, this article conducts a thorough self-reflection on Mazen Iwaisi’s family project to restore and convert the family traditional house into a local museum. Furthermore, it provides a comprehensive genealogy to enhance the study’s context. Through Mazen Iwaisi’s diligent involvement, on-site visits, and semi-structured interviews with Ali Shreteh, the founder of the local museum in Al Mazra’a al-Qibliya and Fayeq Awais, the founder of the Lamsat Umi Museum in Deir, Dibwan, near Ramallah, explore how these museums came to exist, how they are supported, what they exhibit, and who visits them.

While the text focuses on the three case studies as a first step in a broader project to map local museums in Palestine, it also conveys broader theoretical literature on the topic: Scholars have conducted comprehensive research on private and family museums and collections situated in urban centers like Jerusalem, Ramallah, Bethlehem, and Nablus. However, museums located in small towns and villages have not received the same level of attention. Although the focus of this article is not on the different methods of writing history, our writing is informed by Peter Laslett’s (1987) and Emma Shaw’s (2021) critiques regarding celebratory presentations of history and the strength of family historical approaches. Laslett (1987) cautions against interpreting history in a backwards manner and stresses the importance of a more critical approach. Conversely, Shaw (2021) highlights that family historians, i.e. family members writing the family’s history, despite their lack of formal training in research methodologies, display a nuanced understanding of the principles of historical analysis when creating and sharing their familial histories. Our study emphasizes the importance of (self-)reflection in avoiding hagiographic presentations of history, thereby promoting a more critical and nuanced understanding of the past.

Similar observations are made by scholars studying other contexts: Our argument converges with the findings of Mataga et al. (2022: 2) regarding local museums in Zimbabwe. Their study revealed that these museums use unstructured methods and approaches to knowledge production, which are not guided by disciplinary experts. Instead, the community relies on family and local experts who possess a deep understanding of the subject matter. They have a non-linear and fluid conception of time and materiality, making them the preferred source of knowledge within the community.

In doing so, this article challenges the dominant narrative and practice governing museums in Palestine by reflecting on how families assembled their approaches to converting their traditional houses into local museums. This article is also the seed of a larger project to map museums located in rural areas of Palestine that aims to explore local approaches to preservation and cultural heritage protection. The questions that arise are: When families decide to curate and exhibit their private collections, what approach do they follow? What role does their knowledge play in reshaping the definition of the museum? What challenges do these initiatives face? What is the state’s perspective on these efforts? These operational questions are vital to address. Furthermore, more persistent theoretical questions arise. What narratives are established, and what value does scholarship in museum studies add to this debate? Additionally, what are the implications for local communities in terms of cultural representation and the preservation of cultural heritage?

To answer these questions, we base our argument on local know-how related to objects and places that have been marginalised by national museums, which often portray these aspects as mere superstition. Additionally, we draw from Doreen Massey’s conceptualization of the « local » as key to understanding cultural contexts (1994, p. 119). Andrew Fleming’s advocacy further corroborates this notion, proposing that “local matters may engender trains of thought which open much wider issues (the dividend of empiricism)” (2012, p. 461). The study by Mataga et al. (2022, p.3) proposes that privately owned small or independent museums and cultural centers are sites where emergent perspectives can open up. These require a renewed understanding of time and space: We argue that the spatiotemporality of these museums reclaims the family’s agentic role.

Based on the experience of three family museums in Palestine, our article demonstrates how museums built from traditional houses can embody the everyday spatiotemporality of a family and represent an ongoing, dynamic, contested, and evolving process. By speaking of spatiotemporality in family museums, we refer to the active and dynamic presence of the family’s history, culture and materiality within the museum space. The concept allows for the exploration of personal narratives, the preservation of collective memory, and the creation of a meaningful connection between the past, present, and future. The restored house, as a local museum, embodies the everyday experiences of families intertwined with Henri Lefebvre’s idea that the everyday should not only be studied as a significant object of inquiry and a site of conflicts but as a realm of transformation (Summa, 2021, p. 61).

To give attention to such transformations in this article, section one examines the uncertainty of the museum as a cultural institution in Palestine amidst the policies and agendas of the (quasi)-state and NGOs. In particular, we examine the Palestinian Museum at Birzeit University, which received substantial funding of $24 million for its construction in 2016. While the museum is crucial in showcasing Palestinian culture, its presence has inadvertently diminished the visibility and accessibility of smaller local museums in nearby towns and villages. Meanwhile, section two examines how family reflection allows for a shifting episteme in restoring the agentic spatiotemporal life of family museums in Palestine. “These small, independent museums present an opportunity for local communities to foreground their cultural selves, curate their own representation, and tell stories from their experience” (Mataga et al., 2022: 2). Therefore, we believe it is essential to provide support for smaller museums, which have managed to persevere in the face of various challenges, including lack of funding, whether from public or private sources. Section three presents three case studies that show the museums as spaces of living practices.

The (quasi-) state and NGOs and the uncertainty surrounding the museum as a cultural institution in Palestine

In the past decade, there has been increased criticism within Museum Studies, which highlights how national museums in Africa and Asia are direct products of museums established during the colonial era (Chambers et al., 2014). Such interpretations align with Mataga et al., who states that “the narrative of the smaller cultural groups has largely been excluded in the narratives and displays at the public-owned institutions” (2022, p. 20). New critical directions have examined the evolution of museums, how they are perceived, and how they can be improved and sustained. The purposes (Hooper-Greenhill, 2007) and ethics (Marstine et al., 2013) of many museums have become increasingly critical, focusing on transparency, repatriation, and ethical collection practices. Moreover, aims and practices (Vartiainen & Enkenberg, 2013), representations (Moira Simpson, 2012), and the transition of museums from modern to postmodern have challenged the traditional view of communication and education within museum settings (Mejcher-Atassi & Schwartz, 2012, p. 17). This paradigm shift has resulted in a greater emphasis on visitor experience, multiple perspectives, and the exploration of diverse narratives, ultimately fostering a more inclusive and dynamic museum environment. These changes have been stimulated by new cultural, political, and economic factors and influenced by the shifting interests of the public. Museums have had to contemplate how to fit into an ever-changing world and provide meaningful experiences for their visitors (Falk & Dierking, 2011).

While the literature on family visits to museums has flourished both quantitatively and qualitatively in Europe and North America (Beaumont, 2006; Watson, 2007, 2020; Wu et al., 2010; Black, 2012; Povis, 2017), Arab research on this topic has been relatively underdeveloped (Boushnaki, 2011; Muna, 2015). Collection practices are often mentioned in studies on the development of modern and contemporary art in the region (Mejcher-Atassi and Schwartz, 2012, p.18-20). The focus was merely on museums in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Mejcher-Atassi and Schwartz explain that « the recent museum boom in the Gulf coincides with global developments and raises a number of questions about art production and consumption » (2016, p. 11). Scholars, therefore, have an opportunity to examine museums’ roles as public spaces in critical discourse as a result of their significance to the broader community. There remains a need to examine the experiences and reflections of Palestinian families and tourists when they visit museums, as well as their perceptions and expectations.

The inauguration of the Palestinian Museum in 2016 at Birziet University has fashioned the work of many scholars exploring the birth of the museum as being « the brain-child of a group of wealthy Palestinians from the diaspora » (Cobbing, 2016, p. 155), a « space of critique, resistance and decoloniality in the convoluted colonial context of Post-Oslo Palestine » (Toukan, 2018, p. 18). Meanwhile, De Cesari’s (2010, 2019) comprehensive studies on governmentality suggest how the politics of heritage amount to the cultural struggle for Palestine, arguing that it is anticipatory of a [quasi]-state-to-come. Lila Abu-Lughod argues that it exemplifies an Alter-Native conception of self-determination, one of the many ongoing experiments with alternative sovereignty (2020, p. 23). The Museum is a space that exhibits Palestinian resistance to Israeli colonialism, according to Burke (2020). When reading their work, a small opening for critical assessment seems to appear. Fortunately, the family reflection approach offers an opportunity for our scholarship to embody locally shaped experience. Such reading is consistent with the assertion by Mataga et al. (2022: 2) that the locals develop « their methods and approach to knowledge production [as being] unstructured and not abrogated by disciplinary experts, preferring the local connoisseurs of knowledge within the community who are organic experts, whose conception of time and materiality is non-linear and fluid ».

Sheila Watson adapts the definition by Aronsson et al., (2012) of national museums as « those institutions, collections and displays claiming, articulating, and representing dominant national values myths and realities » (2020, p. 3). Such a definition is hard to apply to the quasi-statehood of the Palestinian National Authority. « [T]he [Palestinian] [M]useum’s trajectory after the inauguration shows both an institutionalizing push and an ongoing experimentation, a dialectics of institution building and institutional critique » (De Cesari, 2019, p. 180). This dialectic of institutional critique will persist, whether it is focused on the Palestinian museum at Birzeit University, the establishment of a national Palestinian Museum, or any other museum. The question of how long this cycle of institution-building in Palestine will last is still unknown. Have we stagnated in the permanency of the status quo of a quasi-state? Felicity Cobbing’s article delves into the primary mission of the Palestinian Museum. Cobbing states that « if it is to be a museum and not primarily a venue for other things, [its mission] is to collect, research, and exhibit material » (2016, p. 156-7). The museum seems to be struggling to fulfil such a transformation as it is primarily a space for ethnographic-oriented exhibitions and a digital archive. The museum « hopes to develop an exhibition on the archaeological heritage of Gaza, using the al-Khouday archaeological collection as its core » (Cobbing, 2016, p. 156-7). Baha Jubeh2, a curator at the Museum, clarified that the exhibition of the al-Khouday collection has yet to come to fruition (Phone Interview, February 2024). The al-Khouday collection is presently stored in a warehouse in the port in Geneva, Switzerland (Iselin, 2023).

Scholars have challenged and redefined various aspects of museums, such as the (post)-colonial identity at their core (Arinze, 1999; Mawere, 2015; Bodenstein et al., 2022). Post-colonial identity in museums refers to how museums represent and interpret colonial histories and the legacies of imperialism and how they reevaluate them to acknowledge and address the power dynamics, biases, and distortions of the colonial era while striving for a more equitable and inclusive representation of diverse cultures and perspectives in museum narratives. The museum was part of institutional development and a step in the process of forming an independent Palestinian entity (Tamari, 2012, p. 85). The critique, however, shows that « the nation-state has lost its special place in the political imagination » (Abu-Lughod, 2020, p. 23), and the PNA continues to operate on the ground despite all the odds of its reasons and justification for its existence. Another reading of the Palestinian Museum comes from Hanan Toukan (2018), who adapts Joseph Massad’s (2000) description of the « postcolonial colony » in Palestine. Toukan (2018, p. 10) begins with an examination of « the paradox of living in a state without sovereignty in the West Bank and Gaza under the guise of a diplomatic process leading toward a two-state solution ». While recognising the strength of postcoloniality as a conceptual tool, its blind spots, such as the fluidity and perceived lack of a cohesive single understanding within a theoretical framework, should be recognized (Mataga et al., 2022, p. 9). One limitation of using postcoloniality as a conceptual tool is its inability to capture the complex dynamics and power relations within the Palestinian context. The postcolonial colony avoided examining how such apparatus of the PNA status quo survived and became a permanent feature instead of being transitional towards sovereign statehood.

We argue that the clientelist politics (Amundsen and Ezbidi, 2002) of the PNA is a more appealing framework to study the socio-economic realities and transformations in Palestine when it comes to studying museums in particular and cultural heritage in general. It provides insights into the dynamics of power and wealth in Palestine and how it is used to maintain the existing status quo. Such an approach has been advanced by Tuastad (2010), who argues that international policy has contributed to the maintenance of internecine Palestinian violence, with the promotion of clientelism over democracy being a key factor. Meanwhile (Arda and Banerjee, 2019) advocate that such social relations have become dis-embedded from the local context and re-embedded in new relations with international donor organisations, resulting in a depoliticised public sphere. Let us, however, direct our approach towards Anas Iqtait’s recent work, which argues that the economic framework of the Oslo Accords enforced on the Palestinians an arrangement, the so-called clearance revenue mechanism, whereby the occupying power, Israel, could maintain its supremacy to collect and transfer (or not) indirect taxes to the PA on a monthly basis, (2023, p vii). The arrangement illustrates how aid and the public sphere are always politicised, explaining the broader context of control and dependence perpetuating development denial and de-development cycles (ibid). It also shows how different groups navigate this system to their advantage.

The reality of such clientelism is that the Palestinian Museum is still operating in the shadow of Israeli settler colonialism, which imposes an immense impact on its decision-making, funding and operations. Adopting a clientelist approach to politics, therefore, looks beyond the needs of the community to the interests and agendas of the political elite. As a result, the museum could lose its ability to serve as a platform for community engagement and expression, limiting its impact and relevance.

In the following section, we explore the difficulties encountered by three family museums situated in small Palestinian towns and villages. These museums are frequently overlooked in light of the bigger and more notable museums located in metropolitan areas. Despite the challenges they encounter, these museums possess countless narratives that are deserving of preservation.

Self-reflection: Beyond the family-based to a community-based approach

When she passed in March 2023, my grandmother left behind an impressive legacy spanning four generations of her descendants. Although she lived an ordinary life as a Palestinian woman from a small village in the West Bank, the question of what constitutes « ordinary » opens up discussion about how memories and objects of ordinary people find their way into museums. Her dreams before she passed are particularly striking. In the last few days of her life, she would hold our hands and share these visions. One such vision that stood out was of herself in a white decor in the attic of my family’s traditional house, dressed as a bride. While my grandmother never lived in that house, to her, it was still a memory rather than a physical experience, testifying to the importance of the imagination of the place.

The family approach to the museum exhibits a journey into emotions, sensations, and perspectives that transcend the linear and sequential nature of storytelling. The argument the authors will present goes hand-in-hand with Macdonald’s position that museums are not only structures but also processes and « contested terrains » (1996, p. 4). In light of this contest of meanings, museums, according to Lavine and Karp (1990, p. 1), can be seen as sites of negotiation and interpretation, where different interests compete to shape the meaning and experience of the collections they host. Museums are also sites of memory and identity, where exhibitions and displays can evoke powerful emotions and a sense of shared experience. Conversely, the seemingly dry, technical and neutral process of preserving artifacts from the distant – or not-so-distant – past, is also an operation fraught with political decisions and societal consequences. The most « natural » location for the intersection of these forces are the museums with the special places they hold for the Bildung and self-image of sovereign nation-states. It is the responsibility of these institutions to collect and preserve objects and to make collections accessible to the general public (Burke, 2020, p. 361). Macdonald and Fyfe (1998, p. 2) argue that « museums are symbols and sites for the playing out of social relations between identity and difference, knowledge and power, theory and representation » (1998, p. 2): museums are, in themselves, indicators of the history and the powers that built them and of the intentions and projects that underpinned their material construction and the selection of their « important » collections.

These concepts should enable a more holistic and multidimensional understanding of museums, which sheds light on the nuances, contradictions, and complexities of any such structure that should make the public aware and offer the public a more complete experience of it. In other words, the narrative underpinning the selection of items, the highly curated collections made available to the public, is and should not be beyond the scope of examination. In this light, a conscious family approach aligns with what Brooks (2022, p. 19) has recently advocated in his critique of the dominance of narrative and story-telling over more complex understanding: « What we need may rather be an analytic unpacking of the claims for narrative, a clearer understanding of what can and cannot be accomplished ».

By closely scrutinizing the assertions presented in the various narratives implicit in museum assemblage, we can develop a more profound comprehension of how our perception of the human experience is influenced by cultural factors, biases, and assumptions. This analytical approach enables us to interact with museum narratives in a more sophisticated and knowledgeable manner.

To return to my own narrative: the renovation of my family’s house and planned conversion into a local museum was not initiated with museal intentions. It began, instead, years before my grandmother’s death, as she sat in a chair in the shade of the vineyard, watching her grandchildren renovate the house. Such a fond memory also reminds me of my grandmother’s reluctance to sell our grandparents’ old traditional house, very close to ours and to my father’s. Her argument was that the house should be passed down to my uncle, who lives in Chicago, as his share of the inheritance. As the grandchildren of her daughters, we always detected her bias towards male children. She was always at odds with my father and did not like him as a son-in-law. She also had her own ranking of favourite sons-in-law, and it is unclear where my father fell on that list. Despite her biases, my grandmother had a tremendous sense of humour and could mimic almost anyone in the family. She was a skilled storyteller, and we would gather in the courtyard of their house, several generations of us, to demand that she flavour the evening with her personal tales. As a grandmother, she had a special status as a storyteller, a status reinforced by her talent and the way she combined imagined and real anecdotes. In her lifetime, our family (the audience) always implicitly complied with this storytelling legitimacy and not even my grandfather (her husband) ever undermined that legitimacy or challenged the anecdotes behind her narratives.

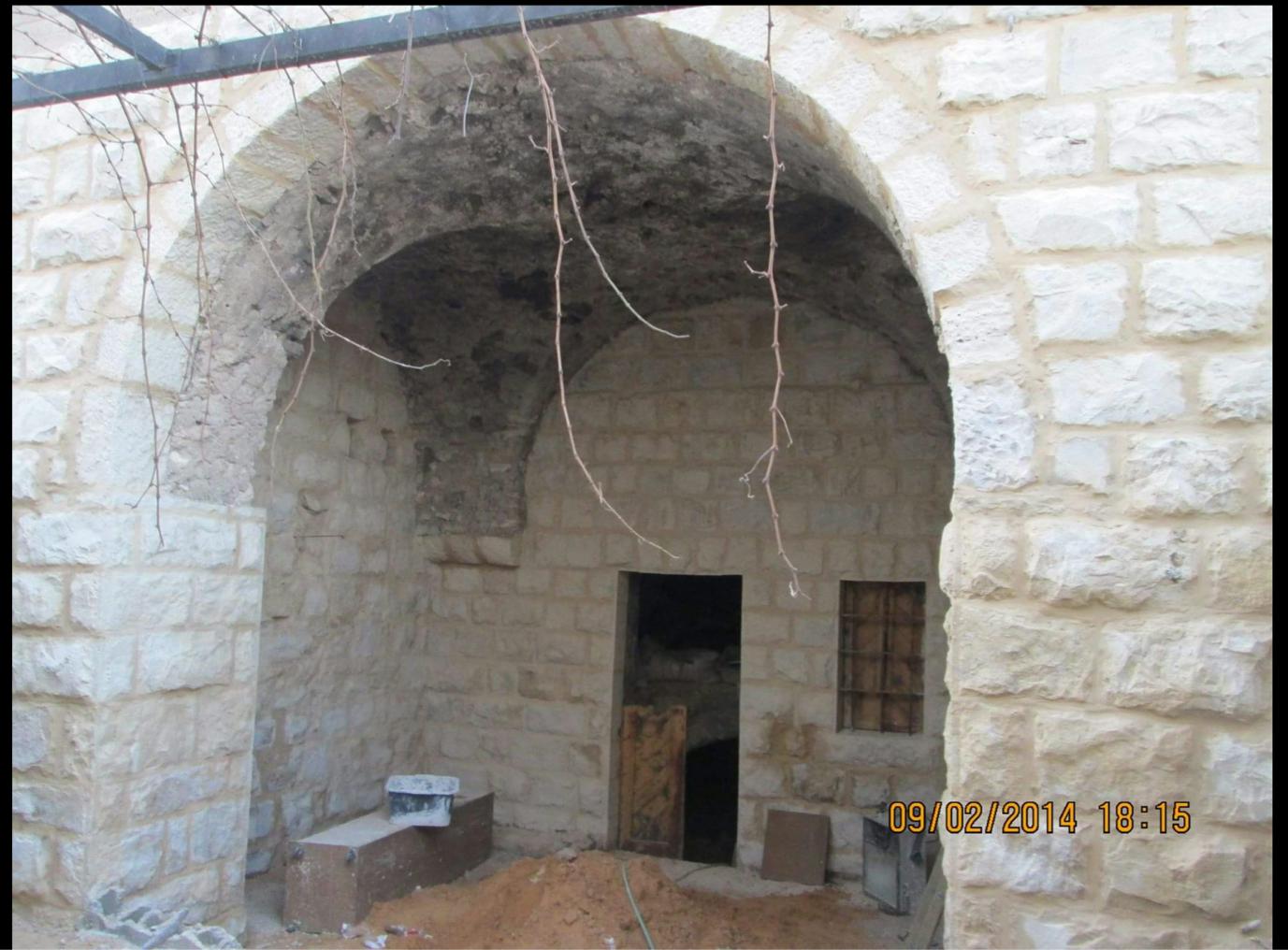

Fig 1. 1st stage of renovating Mazen Iwaisi’s Traditional House in 2014 (courtesy Monther Iwaisi 2014).

Fig. 2. Yousef Iwaisi renovating the external walls of the family’s traditional house (courtesy Mahdi Iwaisi 2024).

This section explores how the ongoing renovation of my family’s house to transform it into a local museum has raised the question of which memories need to be preserved and how to achieve it. This process involves self-reflection and delves into an epistemological apparatus to restore affection, knowledge, experience, living legacy, success, and doubt in families’ experience of preserving and managing their cultural heritage. By doing so, families’ agency in preserving and managing their cultural heritage is restored and their silenced narratives are epistemologically accredited.

The family museum, as we have said, is a locus for memory where artefacts are placed to represent certain lived experiences linked to spaces and subjects selected to serve one narrative direction from so many other directions. Such reading aligns with Mejcher-Atassi and Schwartz’s (2012, p. 17) claim that “objects […] combine with the exhibition apparatus to produce a ‘narrative’ that unfolds within a broader social and material context ». In other words, the museum acts as a performance of memories. These narratives remind us that history is not just a series of facts but rather a curated selection of them.

For all museums, and especially those focused on family experience, the problem inherent in the selection process is how such a structure can enable a multiplicity of voices, how a typical single narrative – a focus, indeed – can transform itself into a spectrum of knowledge and experience for a wider public. The authors here acknowledge how, in terms of engagement with the public and maximisation of available resources, one of the best solutions would be to intersect one museal line – e.g., thematic – with any other, be it chronological, interactive or designed for a specific targeted public (children, disabilities, minorities). However positive it may look in theory, one must also recognise the prerequisites and postulates it imposes on the public: that, at any intersection, their existing knowledge will enable them to recognise all the possibilities without falling into a realm of relativistic confusion or purely sensorial pleasure from the sheer multiplicity of possibilities. A museum is a location of choices – societal, political, and economic, but it cannot exempt itself from giving the public firm grounds on which to exert their freedom. The deontological rationale for a museum should always maintain the freedom of the public and the epistemological awareness of the curators toward their choices and those they are offering to the public. Concordantly, a series of questions must be made explicit if we want to maintain the broadest panoply of freedom possible with an informed public: can the public handle multiple performances/narratives at once? Is the museum presenting artefacts in a clear narrative direction with a beginning, end, and/or continuation? Does the museum focus more on the ethical or « pathetical » aspects of narration rather than analysis? Regardless of the narratives presented, does the museum encourage us to reflect on choices, biases, and values? What emotions does it evoke, and what ethical questions are raised?

To lend further credence to these inquiries, we reassert and agree with Peter Brooks’s recent sympathetic interpretation of Galen Strawson’s 2004 critique of narrativity, « especially the implicit claim that living is identical to one’s telling about living » (2022, p. 19). To the authors of this article, this « fictitious » equivalence seems to be both the power-base and the unfinished bridge of the narrative-turn applied to museology. By immersing oneself in exhibits and artwork, one can encounter the full breadth of the human experience outside the bounds of storytelling. In this manner, museums become a hub for exploring alternative avenues of comprehending and valuing life, unconstrained by the limitations of narrativity. Brooks (2022, p. 19) goes further to argue that « if narrative can’t be the sole tool—as Jakobson’s two poles of language suggest—it also cannot be dismissed. Strawson’s rejection of narrative may be usefully polemical, but it cannot be our resting place ».

As we delve into our museum transformation, we address several critical inquiries. What memories to ex/include? What artefacts to project and what to store? What stories to tell and what stories to hide? Such questioning brings back my grandmother’s stories in assembling Dar Hassan Ballouta’s local museum to question if the museum, be it any museum, might be embarrassed by its artefacts and/or memories. The latter question, moreover, evokes memories of my grandmother’s stories and reminds us of Strawson’s (cited in Brooks, 2022) critique of our grandmother’s narrativity or of any other subject to be included in our museum as a family; we recognise that « the implicit claim that living is identical to one’s telling about living » is challenging in its accomplishment. Such a claim prompts me to question if a museum, regardless of its subjects, can truly be embarrassed by its exhibits or memories. Does such a sense of embarrassment apply to objects? It is beyond the purpose of this article to answer all these questions; however, it does open up the possibility of rooting self-reflection in the context of families assembling their local museums so that they can regain their active agency in knowledge production.

The materiality of my family’s museum, however, is no less important than the memory component. This materiality is manifested in the renovated traditional house and material objects for exhibition. The renovation turned fully into a family affair following the failure of the Palestinian Department of Antiquities (PDA) to fulfil promises to partially assist in renovation. Riwaq (Center for Architectural Conservation) was also promised to send experts to supervise. Both entities, however, failed to get involved. This failure demonstrated the unreliability of Palestinian official institutions and NGOs, even though I have so many friends working in both whom I respect. My family started the first stage of restoration in 2014, which included cleaning the exterior stone walls and filling holes. We followed Riwaq’s restoration manual and my family fully covered the overall budget of 2,000 USD. In the next few years, we continued limited restoration, but the budgetary constraint was the main obstacle in fully completing restoration. The turning point took place in 2021 when my father purchased two neighbouring traditional houses that belong to our grandfather and his brother. The ownership of 3 houses is of a total area of 450 square-meters, which contain 4 rooms of 30 square-meters each. Such a space re-ignited the idea of turning the place into a museum, if not fully but partially. The purchase of the two houses again put financial pressure on the family as the overall cost reached around 30,000 thousand USD. However, the fact that the houses belonged to the extended family, it was possible to set up a monthly instalment rather than paying one lump sum. While adding two houses to our original one was a cause for celebration in the family, the purchase also created tensions and envy that we had to deal with.

In December 2021, I participated in an event organized by the Palestinian Ministry of Culture in Amman, Jordan. The event, « New Approaches Toward Building a National Historical Narrative for Palestine and the Region, » provided a unique opportunity for me and Jamal Barghouth (co-author of this article) to connect with colleagues and experts in the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) and the region, both personally and professionally. During the event, I had the chance to discuss the potential support for my family’s museum project with the Palestinian Department of Antiquities (PDA). I was successful in persuading the PDA to carry out two two-day archaeological surveys of my village, Al-Lubban Ash-Sharqyia, which is home to six archaeological sites dating back to the Bronze Age right through to the modern era. The area is also subject to colonial Israeli settler biblical claims, which have led to the construction of settlements, land confiscation, military installations, agricultural activities, and archaeological excavations in collaboration with American evangelical organizations, such as the Associate of Biblical Research. One of the primary objectives of the survey was to investigate the spatiotemporality of archaeological sites such as Khan Al-Lubban. There is a possibility that the site may be confiscated by Israeli settlers since there are biblical claims attached to it. Thus, the survey team is working on a report and an article to reevaluate the spatiotemporal significance of the site. Prior academic research in the vicinity of the Khan has unearthed flintstones and shards of pottery from various periods. According to previous studies, it is thought that the building is connected to both the Ottoman and Mamluk periods. Our architectural analysis, however, suggests that such periodisation needs to be reconsidered since the stones clearly belong to earlier periods, and their original location (in-situ or off-situ) and their reincorporation into the structure suggest a new hypothesis.

My family and I signed an agreement with PDA, confirming that they would provide restoration materials and we would provide the labor. Unfortunately, the PDA delayed the process and failed to fulfil its promises. As a result, my family decided to take responsibility for the renovation and governance of the site. We began the process again in November 2023 and are hoping to complete it with our own financial support by August 2024. This story highlights the stereotypes surrounding the relationship between the state and family in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, particularly in Palestine, a quasi-state that seems to be trapped in permanent stasis. In the face of these dysfunctionalities, our family has resisted and demonstrated our own faith and in each other by taking matters into our own hands and completing the renovation ourselves.

In the Shadow of the Palestinian Museum: Ali Shreteh‘s Family Museum

The struggle encountered by my family and the ethical considerations related to being a Palestinian scholar in archaeo-politics have prompted myself and my colleague Jamal to search for additional family stories and explore the challenges involved in assembling family museums. It is in this respect that the Ali Shreteh Family Museum stands out as one of the most intriguing examples of how individuals can assert their agency in the shadow of a massive museum supported by the authorities (Cobbing, 2016, p. 155). Ali Shreteh’s efforts in collecting objects and documents goes back to the mid-90s. He used his own house to store objects. In 2020 however, no space was left. She turned to the family traditional house, which is still in shared ownership among the siblings to turn it into a museum. The family undertook the responsibility for the renovation with no external aid from PNA agencies or from Riwaq. Following the partial renovation of two rooms, Ali moved the collection to the traditional house, which was inaugurated with family, friends and locals from the village gathering in 2020. It should be noted that Ali Shreteh’s museum contains more objects than the Palestinian Museum at Birzeit University. The irony of this situation is that the latter « opened without an inaugural exhibition, and debates continue regarding the usefulness of a permanent collection » (Burke, 2020, p. 361). Burke advocates that this situation is representative of how « the museum has been profoundly affected by the sustained control and violence of Israeli policies, and by the fragmented and compromised abilities of the Palestinian Authority » (ibid., see also De Cesari, 2019, 2010). Burke adds, « as the museums’ staff and board have explicitly recognized, due to the occupation much of their intended audience are unable to physically visit the museum » (Burke, ibid.). This academic rationale for the Palestinian Museum is woven into the concept of sumud which translates as « steadfastness » (Burke, 2020, p. 361). Yet, we must also acknowledge that sumud constitutes a dynamic everyday steadfastness for Palestinians. As long as the Israeli colonial regime remains in place, such sumud will be circular: it is repeated over and over again. Sumud is a helpful concept when seeking to understand Ali Shreteh’s everyday struggle in renovating his family’s traditional house and curating his extensive collection in the face of pressure from affluent Palestinians to sell. In a personal communiqué, Ali Shreteh revealed that the staff and board of the Palestinian Museum approached him to donate his collection to the museum. The struggle of Ali Shreteh’s family museum goes hand-in-hand with that of Mataga et al. theorisation (2022, p. 2), that « ‘private’ [and family] museums continue to exist at the margins [and shadows] of the (state) structures and exist at the fringes of normative disciplinary practices”. This marginalization presents their uniqueness and also “presents an opportunity for the museum fraternity to rethink the place, role, and function of museums at the community level” (ibid).

Haber’s (2012, p. 62) notion of “knowledge from the margins or borderlines” and shadows suggests that the everyday « takes into confidence local communities, indigenous peoples, popular cultures […] weaving relationships, and producing counter-hegemonic theorization from the exteriority of the West » (Haber, 2012, p. 63). Ali Shreteh’s family museum is a prime example of counter-hegemonic museology in Palestine. By preserving and showcasing his collection outside of the Palestinian Museum, his museum challenges the dominant narratives perpetuated by the state and NGO apparatus. This resistance empowers local communities to reclaim their own ways of cultural heritage preservation rather than conforming to national clientelism. Private and family museums have an essential role in redefining the place, role, and function of museums within the community. This form of resistance and liberation from elitism and normative disciplinary practices is crucial for cultural heritage preservation.

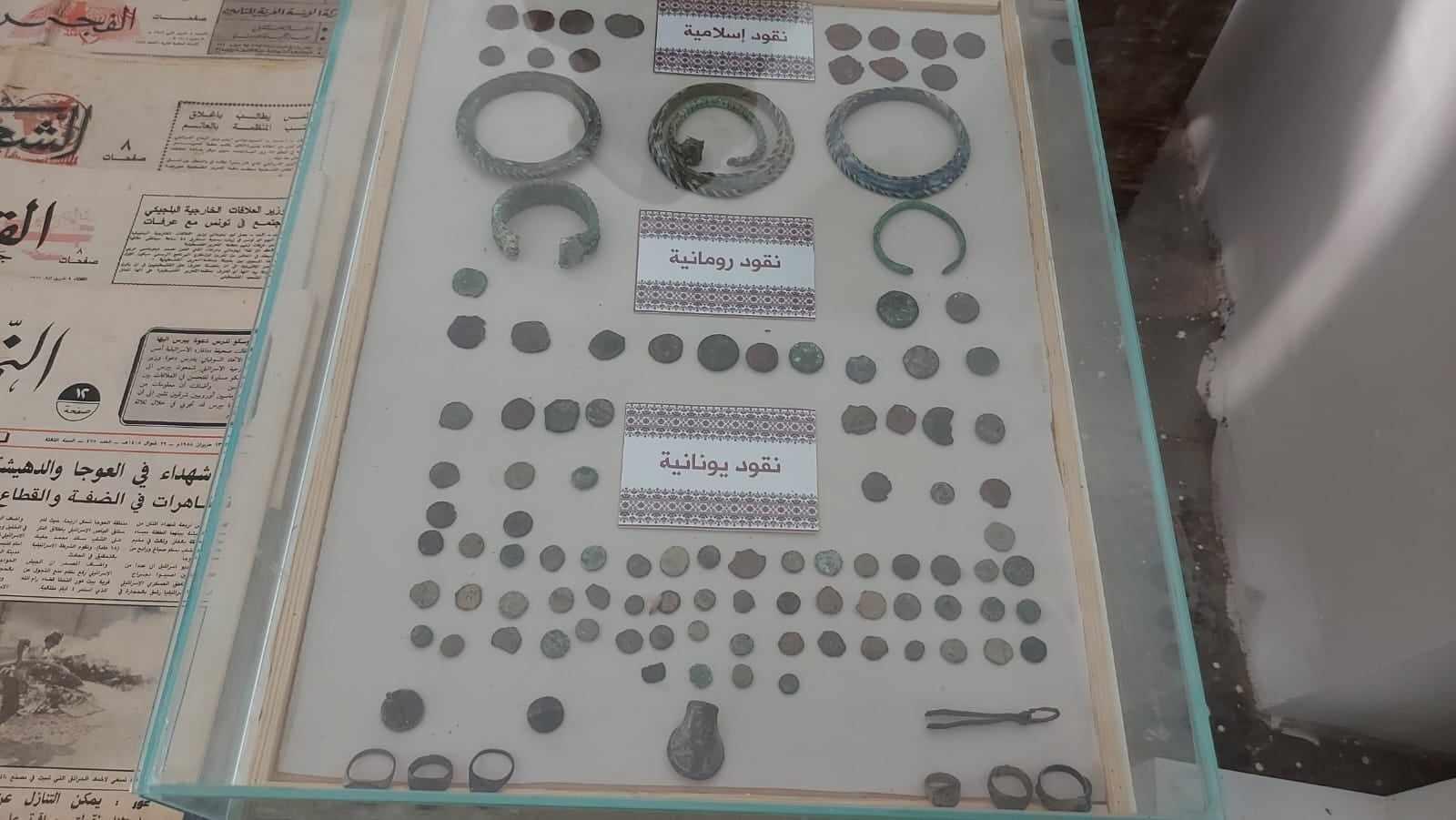

Fig. 3. A collection of objects from different (courtesy of Ali Shreteh, 2023).

Fig. 4. A collection of coins from the Islamic, Roman and Greek periods in Palestine (courtesy of Ali Shreteh, 2023).

Ali Shreteh started his passion for collecting objects back in the mid-90s. Over 300 objects are exhibited in his family museum. Ali stated that around 60% of them are donated by families and individuals. When Ali was asked about how people came to know about the museum to give their personal objects and documents, he reflected on curators’ ethics and trust. He added that people have different reasons to donate or sell their objects and documents. In his case, however, he established his approach as that of a curator rather than a trader, which encouraged people’s trust. Meanwhile, the rest of the collection was purchased by self-finance. Ali also revealed to us that he managed to obtain from a family member over 500 documents of the village that go back to the Ottoman and British Mandate Period. Ali appealed for his collection to be professionally classified and curated to support his family initiative. The authors agreed to organise a workshop in August 2024 in Ali’s family museum and call on local experts to aid his efforts in maintaining and potentially expanding his efforts. This article is also the seed of a larger project to map museums that are located in rural areas in Palestine, aiming to explore local approaches to the preservation and protection of cultural heritage. Lamsat Umi Museum in Deir Dibwan illustrates how curation is borderless and contradicts the perception of the locality as particularism, exclusivity, inherent selfishness, and essentialism as opposed to universalism (Massey, 1994, p. 119). The museum, rather, establishes a link between the local and global and makes local narratives available through the Palestinian Museum’s digital archive.

From California to Deir Dibwan: Lamsat Umi Museum

The dominant narrative of special collections and artifacts outside the state apparatus, NGOs, and universities in Palestine is often associated with the work of individuals. Tawfiq Canaan’s collection of amulets and talismanic objects is a prime example of how the Palestinian intellectual elite preserved such collections. Canaan’s family donated his collection to Birzeit University, where it is exhibited in the Virtual Gallery. According to Vera Tamari, « the significance of Canaan’s collection is closely tied to its documentation of the diversity of social and religious beliefs and customs practised in Palestine, which reflects the pluralism of Palestinian society » (2012, p. 77). Scholars have conducted thorough research on private and family museums and collections situated in urban centers like Jerusalem, Ramallah, Bethlehem, and Nablus. Museums located in small towns and villages, however, have not received the same level of attention. In this latest case study, we examine the Lamsat Umi Museum, which is located near Ramallah in the town of Deir Dibwan. Its founder, Fayeq Awais, was inspired to return to his hometown in Palestine after spending many years living in California, USA. His love for his town in Palestine was the driving force behind his decision to return to Deir Dibwan. The traditional family house was preserved like many traditional houses in the town, contributing to the good preservation of the traditional center of Deir Dibwan. The restoration was self-funded by Fayeq, and his idea from the start was to establish a local museum. Starting with his mother’s embroidery dresses and collections, he has curated a diverse collection of objects and documents. The museum has become a hub for women’s embroidery groups of all ages, providing a source of income. Thereby, it questions the validity of the argument made by Mejcher-Atassi and Schwartz (2012) that the process of « museumization » of culture led to the transformation of living objects and artefacts into venerated relics. The authors cite the example of Palestinian embroidered dress, which was elevated as a symbol of national identity at the expense of its original complex meanings within the rural context of Palestinian society. This academic research judges the social patterns of dress and customs of a society from an outsider’s perspective. The authors do not acknowledge that in recent years, there has been a mass return to embroidery among new Palestinian generations, with large family gatherings dedicated to embroidery work, dresses, arts, and crafts as part of the everyday experience. Women are even choosing to wear embroidered dresses at weddings instead of modern dresses.

Additionally, Fayeq collaborates with the Palestinian Museum through the Digital archive platform, making it possible for people all over the world to access a wide range of documents related to Deir Dibwanians from different periods. This means that those living in the diaspora, including the US and South America, can easily access the online archive and connect with their heritage. Fayeq’s approach is aspirational to Mazen’s family museum in its quest to reach out to people from the village who live in the diaspora, including most of the family who live in Jordan but do not possess Palestinian ID or passports to allow them to visit Palestine. Such an approach could also be replicated in other local museums to (re)connect Palestinians around the world to be able to connect the local to the universal.

Fig. 5. A collection of objects from different periods in Fayeq Awais’s family museum (courtesy Mazen Iwaisi 2019).

Fig. 6. Fayeq Awais appears outside his family museum (courtesy Mazen Iwaisi 2019).

Deir Dibwan is a remarkable archaeological site known as Tell el-Tell, which dates back to the Late Bronze Age. This site has captured the attention of Western biblical scholars due to its possible connection to the biblical ‘ ‘Ai described in the Book of Joshua. In 2014, the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) jointly launched a project to transform the site into an archaeological park. Among the proposed changes was the construction of a small museum that displays excavated cultural artefacts from Tell el-Tell and the surrounding area. Unfortunately, the project has not yet been implemented. However, Fayeq and his family have taken it upon themselves to restore their family museum, preserving a piece of their cultural heritage and that of the village. Additionally, Fayeq has fostered cultural exchange and understanding among the people of Deir Dibwan, both in the town and the diaspora.

Conclusion

It has become increasingly important to examine the evolution of museum narratives over the past two decades to ensure that museums are equitable and inclusive when representing diverse cultures and perspectives. Museums have had to adapt to an ever-changing world, shifting public interests, and emerging cultural, political, and economic factors. As a result, there has been a greater focus on transparency, repatriation, and ethical collection practices, with the purpose and ethics of museums becoming more critical. Our study demonstrated how the family-focused museum approach in Palestine contributes to curation in non-conformist and nonlinear methods, breaking away from traditional museums’ standard structures and functions. This approach challenges normative practices such as collection, naming, classification, and categorisation, offering a possible future for diverse and inclusive museum practices. It also supports the possibility of reflecting on how the concept of a museum is adapted to meet the preferences of different sectors of society.

This article highlights three local museums situated in rural areas of Palestine. Yet, this is just the start of a larger initiative. Our objective is to comprehensively chart all the local museums and private collections in rural Palestine and to provide a platform for the creators of these museums to share their stories. Moreover, we aspire to disseminate their expertise on how to curate and showcase exhibitions. In order to involve the local community in the museum initiative, a series of community events and workshops will be held in August 2024 at Ali Shreteh’s museum and Mazen Iwaisi’s traditional family house. These events and workshops will provide opportunities for residents to actively participate in the curation process. In addition, we are considering collaborating with local schools to develop educational programs that engage students in learning about the history and culture represented in the museums. Furthermore, creating volunteer opportunities for community members to contribute their skills and knowledge would foster a sense of ownership and pride in preserving their heritage.

BibliographieBibliography +

Al Ali, M. (2015). Rethinking Visitors Studies for the United Arab Emirates: Sharjah Museums as Case Study. University of Leicester. Thesis. https://hdl.handle.net/2381/37244

Amundsen, I. & Ezbidi, B. (2002). State formation and corruption in Palestine 1994-2000. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute Development Studies and Human Rights.

Arda, L., & Banerjee, S. B. (2021). “Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood: The NGOization of Palestine”. Business & Society, 60(7), 1675-1707. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650319870825

Elgenius, G., & Aronsson, P. (2014). National Museums and Nation-building in Europe 1750-2010: Mobilization and Legitimacy, Continuity and Change. London & New York: Taylor & Francis.

Black, G, (2012). _The Engaging Museum: Developing Museums for Visitor Involvement_, Routledge.

Bodenstein, F., et al. (2022). Contested Holdings: Museum Collections in Political, Epistemic and Artistic Processesof Return. Berghahn Books.

Bouchenaki, M. (2011). The Extraordinary Development of Museums in the Gulf States, Museum International, 63:3-4, 93-103, DOI: 10.1111/muse.12010

Peter Brooks, P. (2022). “Seduced by Story: The Use and Abuse of Narrative”. New York Review Books.

Burke, F. (2020). “Exhibiting activism at the Palestinian Museum”, Critical Military Studies, 6:3-4, 360-375, DOI: 10.1080/23337486.2020.1745473

Candlin, F. (2016). Micromuseology: An Analysis of Small Independent Museums, London, Bloomsbury.

Chambers, I., et al. (2014). The Postcolonial Museum: The Arts of Memory and the Pressures of History. Routledge

Cobbing, F. (2016). “The Palestinian Museum, Ramallah”, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 148:3, 155-157, DOI: 10.1080/00310328.2016.1214408

De Cesari, C. (2019). Heritage and the Cultural Struggle for Palestine. Stanford University Press.

Falk, H. J., and Dierking, L. D. (2011). The Museum Experience. London, Routledge.

Fleming, A. (2012). “The future of landscape archaeology. Landscape Archaeology between Art and Science”, In Kluiving, S.J. and Guttmann-Bond, E.B. (Eds.), Landscape Archaeology between Art and Science: From a Multi- to an Interdisciplinary Approach. Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press.

Harvey, D. (1989). The Urban Experience. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (2007). Museums and Education: Purpose, Pedagogy, Performance. Taylor & Francis.

Hyde, C. (2013). Unlearning a Great Many Things: Mark Twain, Palestine, and American Perspectives on the Orient. Dublin: PhD Thesis in International Studies Program, Trinity College. Accessed via: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1293&context=theses

Iqtait, A. (2023). Funding and the Quest for Sovereignty in Palestine. Palgrave Macmillan

Iselin, S. (2023) Hundreds of archaeological objects from Gaza have been sleeping in Geneva for 15 years. Accessed via: https://www.rts.ch/info/regions/geneve/14561624-des-centaines-dobjets-archeologiques-de-gaza-dorment-depuis-15-ans-a-geneve.html

Kitchin, R. (2016). “Geographers matter! Doreen Massey (1944–2016)”, Social & Cultural Geography, 17:6, 813-817, DOI: 10.1080/14649365.2016.1192673

Laslett, P. (1987). “The Character of Familial History, Its Limitations and the Conditions for Its Proper Pursuit”. Journal of Family History. https://doi.org/10.1177/036319908701200115

Lefebvre, H. (1991). Critique of Everyday Life (Vol. I). London and New York, Verso.

Karp, I., and Lavine, d. S. (Eds). (1991). Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Washington, Smithsonian.

Abu-Lughod, L. (2020). “Imagining Palestine’s Alter-Natives: Settler Colonialism and Museum Politics.” Critical Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1086/710906

Macdonald, S., and Fyfe, G. (1998). Theorizing Museums: Representing Identity and Diversity in a Changing World. Wiley.

Massey, Doreen (2004). “Geographies of responsibility”. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 86(1) pp. 5–18.

Marstine, J., Bauer, A., & Haines, C. (Eds.). (2013). New Directions in Museum Ethics (1st ed.). Routledge.

Mataga et al. (2022). Independent Museums and Culture Centers in Colonial and Post-colonial Zimbabwe: Non-State Players, Local Communities, and Self-Representation. Taylor & Francis

Mejcher-Atassi, S., and Schwartz. J. P. (2012). Archives, Museums and Collecting Practices in the Modern Arab World. Taylor & Francis.

Kaleen. T. P. (2017) Designing for Family Learning in Museums: How Framing, Joint Attention, Conversation, and Togetherness are at Play. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh. (Unpublished).

Shaw, E. (2021). “Historical thinking and family historians: Renovating the house of history?” Historical Encounters, 8(1), 83-96. https://doi.org/10.52289/hej8.106

Simpson, M.G. (1996). Making Representations: Museums in the Post-Colonial Era (1st ed.). London, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203713884

Sterry, P., & Beaumont, E. (2006). “Methods for studying family visitors in art museums: A cross-disciplinary review of current research”, Museum Management and Curatorship, 21:3, 222-239, DOI: 10.1080/09647770600402103

Strawson, G. (2004). “Against Narrativity”. Ratio, 17(4), 428-452.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9329.2004.00264.

Summa, R. (2020). Everyday Boundaries, Borders and Post Conflict Societies. Springer International Publishing.

Tamari, V. (2012). Tawfik Canaan – “Collectionneur par excellence: The Story Behind the Palestinian Amulet Collection at Birzeit University”. In: Sonja Mejcher-Atassi, and John Pedro Schwartz (eds), Archives, Museums and Collecting Practices in the Modern Arab World, Taylor & Francis.

Toukan, H. (2018) « The Palestinian Museum », Radical Philosophy. 203, pp. 10–22.

Tuastad, D. (2010). “The Role of International Clientelism in the National Factionalism of Palestine”. Third World Quarterly, 31(5), 791–802. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27896577

Vartiainen, H., & Enkenberg, J. (2013). “Learning from and with museum objects: design perspectives, environment, and emerging learning systems.” Educational Technology Research and Development, 61(5), 841–862. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24546543

Vella, J., & Cutajar, J. (2017). “Small museums and identity in socially deprived areas”. In Z. Antos., A. B. Fromm, & V. Golding (Eds), _Museums and innovations_, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 30-43.

Watson, S. (2007). « History Museums, Community Identities and a Sense of Place », in Simon J. Knell, Suzanne Macleod, and Sheila E. R. Watson (eds), Museum Revolutions: How Museums Change and Are Changed, London: Routledge.

Watson, S. (2020). National Museums and the Origins of Nations. Emotional Myths and Narratives. Taylor & Francis.

Wu, K., et al. (2010). « Where do you want to go today? » An analysis of family group decisions to visit museums, Journal of Marketing Management, 26:7-8, 706-726, DOI: 10.1080/02672571003780007

Li, M., Lin, G., & Feng, X. (2021). “An Interactive Family Tourism Decision Model”. Journal of Travel Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211056682