The next shot of restitution: scenes from Mozambique

Coordination parCoordination - Catarina Simão

Numéros précédentsPrevious Issues

Coordonné parCoordination - Emmanuelle Chérel, Maureen Murphy et Magali Ohouens

Coordonné parCoordination - Lotte Arndt & Noémie Étienne

Coordonné parCoordination - Charlotte Bigg, Julien Bondaz, Julie Cayla, Fatima Fall, Sokhna Fall, Marianne Lemaire, Anaïs Mauuarin et Carine Peltier-Caroff

Coordonné parCoordination - Honoré Tchatchouang Ngoupeyou

Coordonné parCoordination - Marian Nur Goni

Coordonné parCoordination - Emmanuelle Chérel et El Hadji Malick Ndiaye

Coordonné parCoordination - Lotte Arndt

Coordonné parCoordination - Emmanuelle Chérel

et El Hadji Malick Ndiaye

PrésentationPresentation

In recent years colonial collections have been under the spotlight of considerable public attention due to the intense discussions around the restitution of African artefacts, that are linked to other major struggles (movements against racism and police violence, the removal of colonial monuments, environmental justice) and have given rise to multiple museographic, academic and artistic initiatives around the world. (Nur Goni 2023)

Troubles dans les collections is based on the desire to strengthen dialogue between researchers, artists, activists and curators working in different countries. It focuses particularly, but not exclusively, on the contentious and contested history of museum institutions in Africa and Europe and discusses their possible futures. It seeks to provide a platform for initiating, supporting and amplifying research, artistic projects and positions across a range of languages and contexts. While working to deepen knowledge about collections, it is committed to critical re-examination and transformative intervention of heritage practices since the colonial period.

Reading these 'sensitive' collections and objects (Lange 2016) lies at the crossroads of several cultural conceptions, histories and conflicts. It requires us to work on the “biography of objects” (Appadurai/Kopytoff 1986), the scholarly classifications and divergent imaginaries that have been associated with them, the consequences of the dispossession, loss, destruction of objects, images and knowledge, and their their multiple re-appropriations in the present. This perspective contributes, as philosophers Kwasi Wiredu, Fabien Eboussi-Boulaga and Paulin Hountondji argue, to understanding “traditions” as discontinuities through dynamic historical reconfigurations, that is, an ongoing reappraisal of practices and beliefs (cosmogonies, values, visions, and symbols) and their gestures of “reprendre” (Mudimbe 1994). In other words, instead of looking for stable meanings of material and immaterial cultural heritage in ways that that have been constructed by primitivism, by certain scientific discourses or by the quest for “authenticity”, collections from colonial contexts are here understood in changing historical contexts, themselves constituted by people and institutions with diverse and often conflicting agendas and interests. Building on these discussions, a number of authors have called in recent years for “unlearning imperialism” (Azoulay 2019), “abolishing African art museums” (Nganang 2021) or questioning the male bias of museum collections by focusing on “sheritage” and “herstories” (Cousin, Tassi & Yêhouétomé 2022; Singam 2022).

Troubles dans les collections invites us to « stay with the trouble » (Haraway 2016) and to elicit it in collections (Nadim 2015; von Oswald and Tinius 2020) and museum archives. The journal discusses the historiography of scientific discourses, museographic strategies, and curatorial or mediation practices. It points out omissions, gaps and silences: the flaws of collections’ narratives. Conceived as a research space contributing to the destabilization of words, concepts and taxonomies that have long conditioned the interpretations and modes of conservation of these artefacts, it reflects on ways to reinterrogate inherited categories, including the one that juxtaposes “Western” and “African”, without dismissing the colonial violence and its current effects. It involves rethinking terminologies such as “museum,” “object” or “heritage,” considering languages and cultures that have not conceived of these concepts (Bondaz, Graezer Bideau, Isnart & Leblon 2014; Cassin & Wozny 2014) and focusing on material, symbolic, and semiotic transmissions, activations and resistances. The journal’s interest also lies in the agency of artefacts, their relational participation in changing societies, the variety of their meanings and narratives, and the complexity of cultural processes—including re-appropriations and political subjectivations. In other words, we believe it is important to invent new forms and situations for re-reading and re-imagining these 'heritages' through the practices and the gestures of those who are attached to them.

The diasporic trajectories of objects, knowledge and ideas between European and African museums therefore require special attention to the constant negotiations that accompany their displacement and recontextualization, including in South-South relationships and mouvements. This attention is necessary when confronting trajectories that are often caught up in reifying conceptions that are difficult to deconstruct and threatened by instrumentalization. Thus, on restitution, the Report on the Restitution of African Cultural Heritage by Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr calls for a “new relational ethics” between the North and the South where objects become “mediators of a relationship that must be reinvented (…)” (2018: 33). As objectification is the result of historical relationships, the stake is not the return to an unretrievable past. Rather, fissuring the rigidity of colonial collections can transform them into vectors for future relationships.

Numerous initiatives within museum institutions call upon artists to deal with problematic historical legacies–oftentimes without allowing for structural change. Through the conception of fictitious museums or even of anti-museums, some artists question the scientific and visual biases and put new narratives into focus. Others create works from collection objects, their exhibitions, archives and storerooms, opening up new interpretations as a way of reflecting their history. Conceived as a space for experimentation and transdisciplinary collective knowledge, the role of the museum as a civic space can be reexamined and the potential of new epistemological approaches experimented.

By developing an approach that is both historical and prospective, Troubles dans les collections brings together artistic, academic, literary, philosophical and activist contributions without hierarchy. Conversations, essays, analyses, songs and poems articulate the field of a research conducted by people living, thinking and working in different geographical locations and positionalities, making room for divergent, even opposing, voices in a variety of languages. The journal thus interrogates various forms of knowledge production by taking an interest outside of historiography, multiplying the focal points or switching to micro-historical approaches. Troubles dans les collections is interested in the omissions, aphasias and misunderstandings that these questions raise through a sustained effort of reflexivity.

BibliographieBibliography +

Ariella Aisha Azoulay, Potential History. Unlearning Imperialism, London, Verso, 2019.

Julien Bondaz, Graezer Bideau Florence, Isnart Cyril et Leblon Anaïs (eds.), Les vocabulaires locaux du « patrimoine », Münster-Berlin, Lit Verlag, 2014.

Barbara Cassin et Wozny Danièle (eds.), Les intraduisibles du patrimoine en Afrique subsaharienne, Paris, Demopolis, 2014.

Saskia Cousin, Sara Tassi et Madina Yêhouétomé, “Les bo des Agoojiée / Les amulettes des amazones. Le retour d’un matrimoine oublié?”, Politique africaine, n. 165, 2022, pp. 187-220.

Fabien Eboussi-Boulaga Fabien, La crise du Muntu : authenticité africaine et philosophie, Paris, Présence Africaine, 1977.

Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble. Making kin in the Chthulucene, Durham, Duke University Press, 2016.

Paulin Hountondji, Sur la « philosophie africaine ». Critique de l’ethnophilosophie, Paris, Maspero, 1977.

Britta Lange, « Collections sensibles », in Mathieu K. Abonnenc, Lotte Arndt and Catalina Lozano (eds.), Ramper, dédoubler. Collecte coloniale et affect, Paris, B42, 2016, pp. 289-315.

Margareta von Oswald et Tinius Jonas (dir), Across Anthropology. Troubling colonial legacies, museums, and the curatorial, Leuven, Leuven University Press, 2020.

Valentin-Yves Mudimbe, The Idea of Africa, Bloomington/London, Indiana University Press/James Curry, 1994.

Tahani Nadim, “Staying with the trouble in a natural history museum: working things out together”, November 2015.

Patrice Nganang, “The Abolition of the Museum for African Art”, African Arts, vol. 54, n.4, Winter 2021, pp. 5-7.

Marian Nur Goni, « Restitutions, réparations. Du problème à la question », in Pierre Singaravélou (ed.),Colonisations. Notre histoire, Paris, Seuil, 2023, pp. 152-156.

Felwine Sarr & Bénédicte Savoy, Restituer le patrimoine culturel africain, Paris, Philippe Rey/Le Seuil, 2018.

Bansoa Singam, “Arts de cour des Grassfields et collections coloniales au prisme du matrimoine”, Troubles dans les collections, n. 5, 2022.

Kwasi Wiredu, A Companion to African Philosophy, Malden-Oxford, Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

Crédits images :Credits images :

Numéro 7 : Rosanna Raymond, Acti.VĀ.tion – In.VĀ.TĀ.tion, 2021, Photo: Stefan Marks.

Numéro 6 : Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, Le Cinéma au Sénégal (Bruxelles : OCIC/L’Harmattan, 1983) ©Éditions OCIC/L’Harmattan. Fatim DIAGNE dans Taw d’Ousmane Sembène.

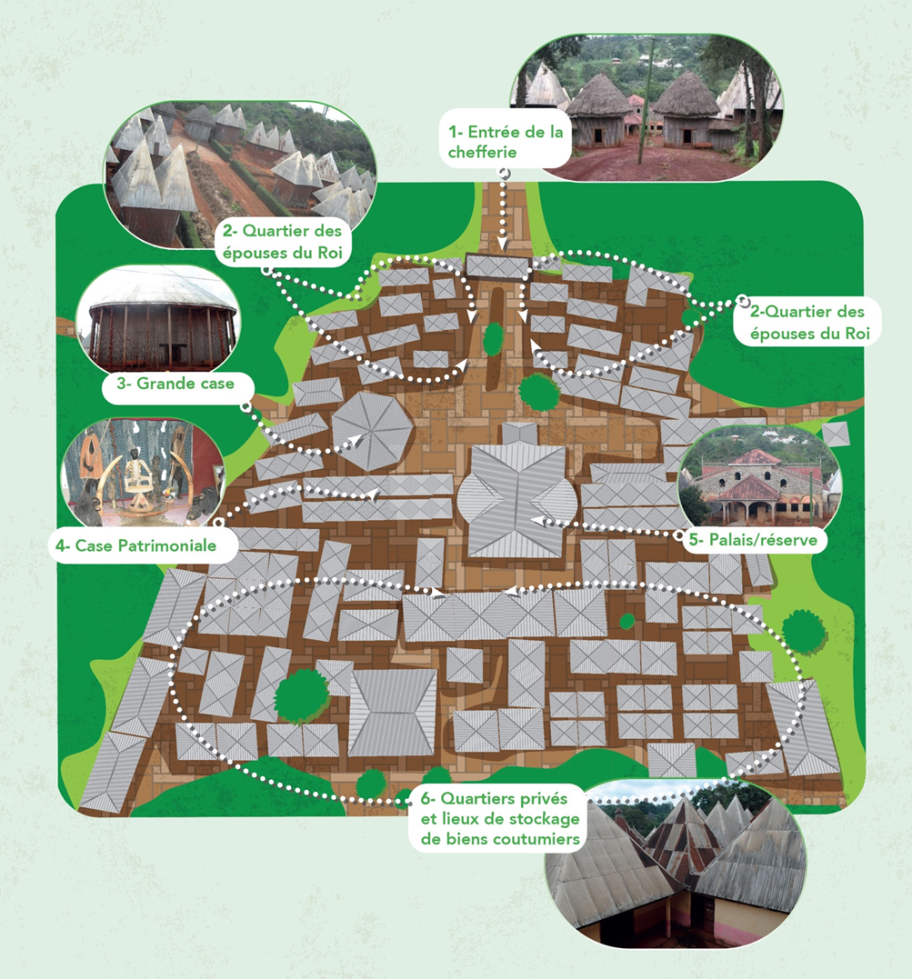

Numéro 5 : Tchatchouang et Biegaing, février 2022.

Numéro 4 : Images issues d’albums de la famille Nur Goni – Comastri.

Numéro 3 : Alioune Diouf, a’Deetnax, se faire dire l’avenir, principes de continuité, dessin brodé, 2018.

Numéro 2 : Matthias de Groof, Palimpseste du AfricaMuseum, Filmstill, BE 2019.

Numéro 1 : Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, Les statues meurent aussi, film ©Présence Africaine.