“They must give back to us the humanity that was stolen from us in so many ways” Paulina Chiziane (1st Sarau Cultural, Noite de Poesia, Mozambican-German Cultural Centre, Maputo, february 22, 2019)

Fig. 1. Titos Pelembe, “Decapture of Ngungunhane protected by the Queens of the Gaza Empire” (2025). Digital intervention on a photograph of the colonial monument exhibited at the Fortress of Maputo (Fortaleza de Maputo, Mozambique).

1.Between legacy and loss: Historical dilemmas of restitution in Mozambique

Global pressures and local resistance: the international arena of restitution

The decolonisation movement, as applied to the arts, monuments, and museums, is likewise a key arena for efforts toward the restitution of cultural property. Objects that were looted or unlawfully removed from their lands during colonial periods served as vessels of Indigenous knowledge and symbolic meaning, acting as extensions of the cultures from which they came. These objects were often subject to conscious acts of destruction—a deliberate erasure widely described by historian Chancellor Williams (1898–1992) in his work The Destruction of Black Civilization (1971), who illustrates how dismantling these cultural assets was part of a broader strategy of cultural erasure and colonial domination.

The subaltern has always spoken (Spivak Chakravorty, 1988), even when not heard by the colonial oppressor, and when the latter finally becomes aware and engages in direct debate about the impact of colonial oppression in the present, new possibilities for healing and critical reflection can emerge. In 2018, French President Emmanuel Macron revived the longstanding debate on the return of cultural property looted during the colonial era, reigniting international interest in the subject. As a result, several countries that were victims of colonial plunder began to express a renewed desire to recover their cultural assets.

The recent case of the Colombian government’s formal request to Spain for the return of the Quimbaya Collection—belonging to the community of the same name and comprising more than 120 gold, ceramic, and stone objects of pre-Hispanic origin currently housed at the Museum of America in Madrid—is particularly significant. There is also a growing determination among several African countries to intensify pressure on the question of cultural restitution.

The Declaration of the Principles of International Cultural Cooperation, issued by UNESCO in 1966, states that “despite technical progress facilitating the development and dissemination of knowledge and ideas, ignorance regarding the way of life and customs of peoples still constitutes an obstacle to friendship between nations, peaceful cooperation, and the progress of humanity.” 1

Accordingly, restitution has, in many ways, broadened the processes of mutual understanding and cultural appreciation among nations, as well as contributed to the long process of reconstructing contemporary history. Some European countries, notably Germany, have demonstrated their commitment to this issue: in 2021, Germany declared its intention to return to Nigeria the set of sculptures commonly known as the “Benin Bronzes,” according to a report by the German international radio station Deutsche Welle (DW, 2021)2. In 2019, Germany returned symbolic artefacts—including Witbooi’s Bible, whip, and the Cape Cross coat of arms—to Namibia, thereby reaffirming its commitment to restitution (Barroso, Borges and Cabral, 2020:40).

Claim and Silence: Contrasting trajectories of Angola and Mozambique

In the case of former Portuguese colonies, the Angolan government intends to submit an official request to Portugal for the restitution of Angolan cultural heritage (Duas Linhas, 2025, October 6)3. In fact, Angola has been investing in this issue since 2011, according to Cerqueira & Severino (2022:235).

Here in Mozambique, silence and the lack of a concrete position regarding the technical, financial, and infrastructural implementation of restitution measures on the part of official bodies still prevail, despite the government’s most recent statement by the current Minister of Education and Culture, Samaria Tovele. During the Africa Day celebrations, she affirmed: “Historical reparations are also achieved through symbolic and cultural means, and that is why we are organising ourselves to debate how we might reclaim what was taken from our country and across the African continent” (Carta de Moçambique, 25 May 2025). The minister’s statements continue to provoke controversy and social distrust, given that, for at least the past decade, the education and culture sector has been notably marginalised. The current lack of investment in the National Art Museum (Museu de Arte), based in the capital, raises structural questions such as: in what way will the government be able to care for looted assets when it lacks both the capacity and, arguably, the will to properly maintain the only art museum in Mozambique? This concern extends to artistic schools, notably the Schools of Visual Arts, Dance, and Music, as well as the Higher Institute of Arts and Culture (ISArC), all of which face various difficulties.

Also, on the occasion of Africa Day, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation, Maria Lucas, stated that “the matter of reparations for Africans and people of African descent also involves reparations for deportations, mass killings, arbitrary detentions, torture, the plundering of natural resources, and nuclear tests with catastrophic human and environmental impact during the colonial period” (Carta de Moçambique, 2025). Clearly, the issue is far more complex than it may appear, as suggested by the minister's remarks; thus, the current challenges characterising the present socio-political, economic, and cultural context remain a long way from encompassing the different perspectives alluded to above.

Canon and counter-practice in post-independence context

The national government’s lack of interest in the arts and culture sector—in direct connection with the central question of this analysis—can also be observed in its distance from the various private initiatives currently under way to mark the 50th anniversary of Mozambique’s independence. Of particular note is the exhibition (Olha)r Moçambique: Revisitar o Percurso Artístico e Cultural4, organised by a collaborative platform of Maputo-based institutions and cultural practitioners. This event included critical discussion sessions on decolonising arts education and reassessing the symbolism of the Fortress of Maputo, a former colonial stronghold whose current configuration still emphasizes Portuguese dominance.

During the exhibition, the artistic community and several researchers engaged in arts education and curatorship (Marcos Muthewuye, Felix Mula, Luís Muengua, Rafael Mouzinho, Otília Aquino, Rufus Maculeve, Sarmento Manuel, Estevão Filimone, among others)—articulated critical positions on artistic decolonisation and the restitution of Mozambique’s cultural property during a roundtable at the Núcleo de Arte on 14 August entitled “Rethinking Arts Education in Mozambique.”5.

Other relevant discussions took place, such as the open talk I organised around Ilídio Candja Candja’s solo exhibition Octopus e Miopia at Galeria Quadrum, Lisbon, in 2021. Moreover, in April 2024, Portuguese president Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa publicly acknowledged for the first time Portugal’s responsibility for large-scale slavery and colonial massacres, signalling a positive shift regarding unresolved colonial issues. The president further called for reparative measures, including debt cancellation and new credit lines for former colonies; however, these statements have yet to result in concrete political actions and have primarily served to provoke media debate.

Accountability and amnesia: Portugal as the former colonizer

In 2018, the Portuguese Directorate-General for Cultural Heritage (DGCP) stated that it had “no knowledge of any claim for the return of works of art, ethnographic pieces, or historical documents, nor has a list of objects subject to restitution requests been compiled” (Expresso, 2018).

On 13 March 2019, the Council of Ministers for Education and Cultural Affairs of Portugal approved a resolution supporting the repatriation of cultural property removed in the colonial context, although no restitution processes had yet been initiated (Expresso, 2019; Público, 2019). Aside from the ongoing Angolan request, no other official claims from fellow PALOP (Portuguese-speaking African countries) are currently known (Expresso, 2019).

Erasure or remembrance: The Fortress and Ngungunhane

In Mozambique, there has been an increasing resonance of voices among thinkers and multidisciplinary artists supporting the restitution of cultural property and decolonisation across various fields of the social sciences and humanities. For instance, the monumental composition of the Fortress of Maputo6 should be reconsidered to grant greater dignity to the heroes of resistance against colonial occupation and domination, most notably the last emperor of Gaza, Ngungunhane7 (1850–1905), celebrated as the “Lion of Gaza.” Ngungunhane was captured in 1895 at Chaimite (a settlement in the Chibuto district of Gaza province, Mozambique) during a military offensive led by the Portuguese cavalry officer, Joaquim Augusto Mouzinho de Albuquerque. He was subsequently condemned to exile in Portugal, dying in 1906 in Angra do Heroísmo, Terceira Island, Azores.

The restitution of Ngungunhane’s remains took place in 1985, thanks to the efforts of the Mozambican government led at the time by the country's first president, Samora Moisés Machel. Since then, Ngungunhane’s remains have rested in the Fortress of Maputo, whose central garden houses a prominent monument to the colonial figure Mouzinho de Albuquerque, as well as two bronze relief plaques commemorating the bravery of Portuguese troops during the battle that culminated in Ngungunhane’s capture. Unfortunately, colonial symbols continue to dominate the visual and historical narrative of this site. Remedying this situation requires developing new plans for the use of these facilities and creating anti-colonial public monuments.

Fig.group 1: Titos Pelembe, “Decapture Ngungunhane protected by the Queens of the Gaza Empire” (2025). Digital intervention on a photograph of the colonial monument exhibited at the Fortress of Maputo.

Despite the intention expressed by the Minister of Education and Culture to seek the repatriation of objects looted by the Portuguese colonial administration, it is still premature to consider this as a definitive governmental decision before parliamentary review and approval. Some political figures, such as former President Alberto Joaquim Chissano, explicitly distance themselves from the minister’s statements. According to Clube de Moçambique (2025), Chissano “rejects the need for reparations from Portugal for its colonial past, instead advocating for good cooperation and reciprocal investment between Mozambique and Portugal.”

Other voices in the cultural sphere, such as writer Paulina Chiziane—an emblematic advocate for the decolonisation of Mozambican society and reparations—have adopted a more critical perspective. In an interview8 with Mbenga-Artes e Reflexões (2019), Chiziane observed that Jewish people9 received reparations after their extermination by the Nazis and their allies during World War II. However, when it comes to Africa, governments “simply say ‘we are asking for forgiveness.’ That is not right,” she stated during the Sarau cultural event “Noite de Poesia” at the Mozambique-Germany Cultural Centre (CCMA), Maputo, in March 2019.

It is also important to note that, unfortunately, several international conventions for the protection and restitution of cultural property to countries of origin were implemented in colonial contexts—such as in Portuguese colonies and specifically Mozambique, then still considered a Portuguese overseas province. The 1972 UNESCO General Conference in Paris stands as one such example, with the adoption of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage on 16 November of that year.

In this vein, subsequent conventions after 1977—such as United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3834 (1983) and the UNIDROIT Convention (Convention on the International Return of Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects, 1995)—were implemented at a time when newly independent Mozambique was already embroiled in a devastating post-independence civil war, which greatly hindered any claims for return. There is thus an urgent need to adapt such conventions to the current context. Even so, these instruments have not proven fully effective, as former colonial powers have yet to undertake the deliberate restitution of heritage. In other words, the country is not yet prepared to embrace the restitution process as an act of resistance and cultural valorisation.

French historian Bénédicte Savoy and Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr have argued that approximately 90% of sub-Saharan Africa’s artworks are held in Western collections (Savoy and Sarr, 2018). While the accuracy of this figure has been challenged by other cultural heritage researchers—who question the criteria for this estimate—it remains true that a significant portion of Africa’s colonial-period material heritage is represented abroad rather than on the continent itself. In Mozambique’s case, leading examples include the Makonde Art Museum (Mie, Japan) and the Makonde Mask exhibit at Berlin Ethnographic Museum (Germany). This may help explain why major exhibitions and fairs on contemporary African art continue to be held primarily in Europe.

2.Artistic (Re)signification as a Practice of Re-(In)s-titution

Fig. 2 Titos Pelembe,“Lion of Gaza, (Re)construction of Fragments from the Memory of the Empire”. Various dimensions (2025).

Artistic resignification as a practice of (Re)Institution

The process of cultural restitution should not be merely a political exercise, but rather a fundamental matter of respect for human rights—given that much of the (im)material heritage in question was looted during European domination. Restitution should also seek to comprehend the complexities of the various traumatic physical and psychological realities that continue to haunt the collective imagination of Mozambicans. For this reason, it remains difficult to conceive how the restitution of plundered objects can ever truly compensate for colonial crimes or the lives of thousands enslaved during European “expansion”. As poignantly described by Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe: “…for the benefit of the Atlantic traffic (15th–19th centuries), men and women from Africa were transformed into human objects, human merchandise, and human currency. Imprisoned in the dungeon of appearances, they came to belong to others—others who took hostile charge of them, depriving them of their own names and languages. Although their lives and labour henceforth became those of others, among whom they were condemned to live, while being forbidden to form human relations, they never ceased to be active subjects.” (Mbembe, 2014:12)

Linguistic and spiritual dimensions are among the most salient aspects highlighted by Achille Mbembe in discussions of cultural restitution and heritage. These elements closely intertwine with the dynamic spiritual energy enveloping African and Mozambican artefacts, many of which remain confined within European ethnographic museums. The typical presentation of these objects in Western institutions strips them of their original context and intended function, a process largely perpetuated by the colonial practice of denying creators individual authorship and assigning impersonal descriptive titles—often out of ignorance or deliberate erasure. This reduction is evident in the standard use of glass vitrines, which isolate objects from physical interaction with viewers and reinforce a classical art tradition that conflicts with the participatory, ritualistic uses central to their origins. European frameworks for exhibiting African heritage tend to prioritize formal aesthetics while neglecting the historical, spiritual, and political meanings these objects possess within their original communities and nations. Within the broader colonial agenda of epistemicide, popular and vernacular art forms were frequently stigmatized, stripped of authorial recognition, and attributed only to collective social or ethnic groups, rather than named individuals. Such museological paradigms not only persist in older institutions but also in contemporary global exhibitions, continuing the practice of referencing European artists by individual names and styles while reducing African creators to anonymous regional or racial designations.

The recognition of Black Mozambican artists in the colonial context during the twentieth century occurred largely in response to mounting international pressure on Portugal to relinquish its African colonies. According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation (2024), Portugal “opposed the decolonisation movement and initiated rapid development in the colonies with the aim of integrating local populations.” In 1951, Mozambique was reclassified as an "Overseas Province," marking a shift in colonial policy. As art historian Alda Costa observes in her study, Art in Mozambique: Between Nation-Building and a Borderless World (2013), the Portuguese authorities began to emulate the strategies of other colonial powers by promoting young local enthusiasts—typically labelled “indigenous”—to the status of artists, and positioning themselves as cultural patrons.

Within this framework, Black artists were valued primarily in accordance with the dominant colonial narrative, especially in Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) under the revised policies of the Portuguese administration—a context in which white Mozambican and Portuguese artists predominated in the city’s art scene, making the recognition of Black creators like Malangatana, Jacob Estevão, Vasco Campira, Elias Estevão, and Agostinho Mutemba notably exceptional.

The valorisation of artists and art produced in Mozambique continues to reflect imaginaries shaped by the persistent force of coloniality in spheres of power, identity, and existence. As Costa notes, a generation of artists gradually asserted themselves “within the polarity between coloniser and colonised, and also as products of inseparable relationships forged between both” (Costa, 2019, p. 9). In northern Mozambique, especially in Cabo Delgado, Makonde art was similarly shaped by pivotal moments in the national historical trajectory. Before becoming a national symbol, it was promoted and commodified by colonial authorities who valued its aesthetics for export and display. Only later did this art transform into a marker of cultural resilience and collective identity in Mozambique’s journey to independence.

These layered histories underscore why restitution cannot be dismissed as a mere act of charity or goodwill; rather, it constitutes an overdue reckoning with injustices of colonial appropriation and violence. The continued presence of looted works in major ethnographic museums in Europe and the United States reinforces ongoing debates that challenge persistent colonial myths inscribed in African consciousness, including notions of European civilization, affluence, and democracy.

Alternatively, restitution can also be understood as an expression of ongoing control and influence exerted by former colonial powers. Crucially, however, restitution—whether of cultural heritage, memory, or political authority—is the direct outcome of prolonged and determined resistance by colonized peoples. In Mozambique, as in other former colonies, the process of restitution was historically preceded by resistance and uprisings among indigenous communities, which ultimately led to twentieth-century independence movements that overturned colonial authority across various societal domains.

Even as political imperatives prompted the adoption of colonial languages as official idioms of the newly independent states, recent initiatives—such as the progressive implementation of bilingual education—have created space for shared knowledge and mutual recognition, marking a profound departure from practices of colonial oppression. Within debates about cultural restitution and international cooperation, a critical question emerges: could the Portuguese government be formally asked to incorporate the native languages of its former colonies into Portugal’s own curriculum? Language, after all, serves as a vehicle of intangible and immeasurable cultural identity and power.

Neither topple nor transform: Restitution as driver for cultural innovation

The immediate replacement of colonial public symbols following decolonisation—such as place names and monuments—represented the rebirth of the Mozambican nation. In Maputo, the former Praça Mouzinho de Albuquerque, now Praça da Independência, was a key public space for the symbolic removal and de-monumentalisation of colonial power. Some statues were moved to the current Fortress of Maputo while others were lost to uncertain destinations; the monument to António de Oliveira Salazar, the former Portuguese dictator, which once stood in front of the school bearing his name, now sits against a wall near the National Library.

Restitution is thus approached from multiple perspectives beyond the mere return of cultural goods; it encompasses a range of multidisciplinary actions required by its underlying complexities. Restitution should equally be a means of returning power and re-appropriate historical and scientific knowledge to African populations. The enduring effects of colonialism are evident in education, for example, in a significant portion of textbooks.

Fig. 3. Ricardo Rangel (1975), “The Other Destiny of Heroes”. Photographic series (Mozambique). Courtesy: Center for Documentation and Photographic Training (CDFF), Maputo.

Fig. 4. Statue of President Samora Machel, photographed by Ildefonso Colaço (2022), Praça dos Heróis, Maputo.

Fig. 3. Ricardo Rangel (1975), “The Other Destiny of Heroes”. Photographic series (Mozambique). Courtesy: Center for Documentation and Photographic Training (CDFF), Maputo. Fig. 4. Statue of President Samora Machel, photographed by Ildefonso Colaço (2022), Praça dos Heróis, Maputo.

Rui Laranjeira, Mozambican historian and researcher, author of Marrabenta: Evolution and Stylization 1950–2002 (2006), emphasised, in his contribution to the debate “Restitution and Reparation in Post-Conflict Identity: Clean Up the House II” (2021)10 organised by Oficina de História (Mozambique) and Mbenga-Artes e Reflexões, the need for greater openness from institutions. Building on this, curator Rafael Mouzinho highlighted the importance of generating new knowledge through valuing local collections—particularly at the Eduardo Mondlane University Museum—and advocated for robust heritage management policies in cultural institutions. He also noted growing concerns among African leaders about restitution, referencing historic achievements within pan-Africanism: the First African Cultural Festival (Algiers, 1969), the pioneering First World Festival of Negro Arts (Dakar, Senegal, 1966 under President Léopold Sédar Senghor), and the First Johannesburg Biennale of Fine Arts in 1995. These and other events have contributed to establishing new references for Africa and its diaspora, both across the continent and internationally.

Restitution poses the challenge of reimagining policies and practices for the creation, protection, dissemination, and appreciation of contemporary African and diasporic art. Increasingly, contemporary debates insist that restitution must serve to restore cultural agency, enable new infrastructures, and cultivate conditions for creative innovation, moving far beyond merely redressing the legacies of historical dispossession. By shifting the focus away from the materiality of objects, restitution emerges as a catalyst for systemic transformation and a source of renewed engagement with artistic practices and cultural narratives throughout Africa and its diasporas.

3.Afrocentric intersection of disobedient artistic and curatorial practices

Mapping or disrupting: Afrocentrism’s double role in artistic practice

The African artistic diaspora and its descendants have launched innovative initiatives to generate new counter-colonial narratives in the contemporary world, addressing and bridging gaps in the global understanding of African art, politics, and religious history through creative practice. A prominent example is the video art exhibition Still Fighting Ignorance & Intellectual Perfidy11, curated by Kisito Assangni, which has catalyzed multi-sited critical engagement in several European countries. Contributing artists such as Titus Kaphar, Grada Kilomba, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Mónica de Miranda, and Francisco Vidal—active across sites including Luanda, Lisbon, and beyond—deploy their work to foreground new perspectives on memory, identity, and the deconstruction of colonial legacies.

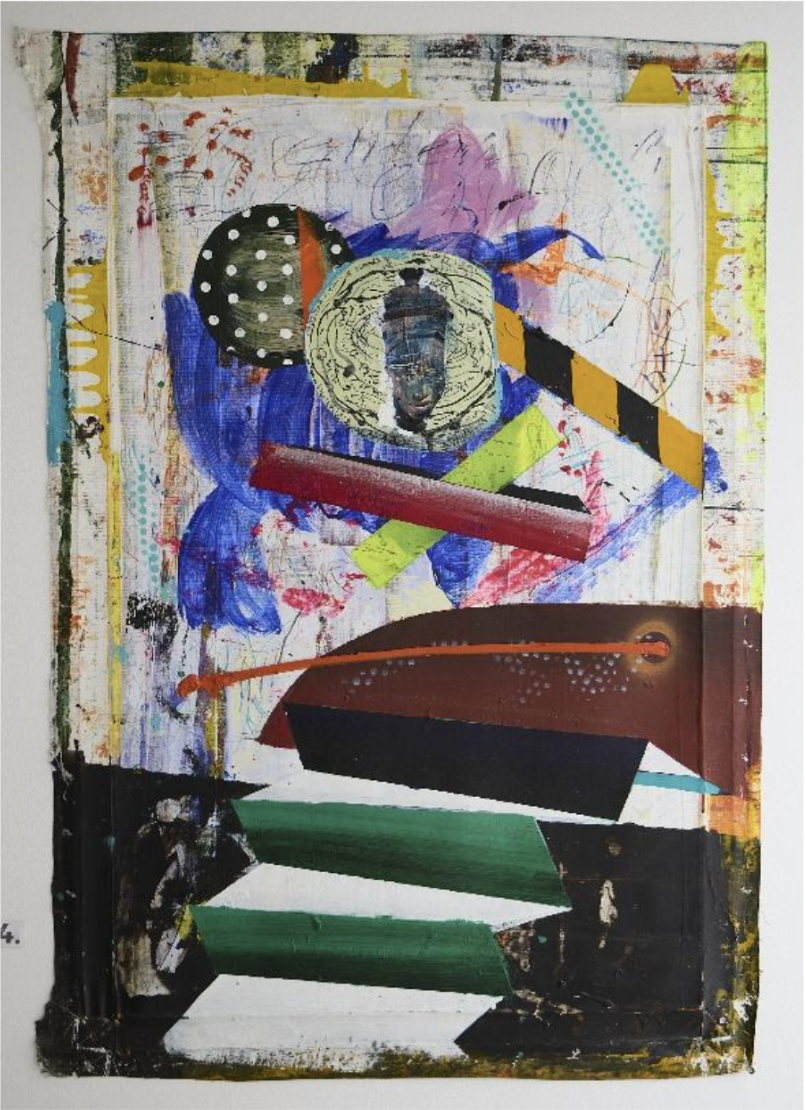

Fig. 5. Titos Pelembe, partial view of the work by Ilídio Candja Candja (2022), “Vodu I–XIII,” various dimensions, mixed media on paper.

The Luso-Mozambican artist Ilídio Candja Candja is a key figure in the artistic production of the Mozambican diaspora, contributing actively to critical debates on restitution and coloniality. Through his practice, Candja serves as an interlocutor in discussions on the meaning and scope of cultural restitution. As he observes, “restitution also means collecting African cultural heritage within Africa, so that future generations may access their references within the continent” 12 (Candja Candja, 2024). This perspective underlines the necessity of ensuring local access to heritage in Africa, broadening the scope of restitution to include preservation and visibility within, rather than outside, the continent.

Candja’s argument reflects an Afrocentric vision aligned with theorists such as Molefi Kete Asante (1980), while also resonating with perspectives articulated by Rui Laranjeira and Rafael Mouzinho, who advocate for institutional openness, enhanced visibility and management of local collections, and a shift towards policies that prioritize the circulation of knowledge and cultural agency within Mozambican institutions. Candja Candja’s recent exhibitions in Europe, the United States, and Africa—especially in Johannesburg and Maputo—seek to illuminate aspects of the colonial past that remain largely unrecognized or overlooked in daily life. His paintings construct a fantastic, utopian imaginative world, experimenting with new pictorial possibilities and articulating critical inquiry through coded visual languages. The exhibition Magnificence, Light and Fusion II (2024), curated by me for Franco-Mozambican Cultural Centre in Maputo, delves into complex spiritual, aesthetic, and political dimensions of decoloniality.

Ilídio Candja Candja’s paintings are a constant search for new ideas and themes, building a visually and conceptually “disobedient” narrative that challenges Western artistic norms. His work seeks to reclaim cultural and aesthetic elements from Mozambican traditions—bringing stories and histories of resistance, often omitted under colonial education, into the present through his art.

Figs. 6 and fig. 7. Moments of interaction with ISArC students following the guided tour that I led as the curator ot Ilídio Candja Candja’s work at the Franco-Mozambican Cultural Centre in Maputo in 2024.

Ilídio Candja Candja’s most recent solo exhibition, Resonance of Form: A Tribute to Sarah Baartman, was presented after Maputo at This Is Not White Cube Gallery in Lisbon in 2024. Across both exhibitions, Candja maintains a consistent critical stance toward the perception and valorisation of knowledge embedded in African traditions and cultures. Through the figure of Sarah Baartman—a South African woman subjected to scientific racism and exhibited in Europe in the nineteenth century—Candja critically reflects on colonial violence experienced by women, exposing its lasting consequences in contemporary society. The artist’s work employs disobedient aesthetic forms, intentionally diverging from academic conventions to express his own rebellion and creative restlessness.

Thus, Ilídio Candja Candja actively contributes to and expands the debate on restitution, arguing that speaking, questioning, and reflecting on the colonial past constitute vital strategies for reclaiming cultural identity, collective memory, and human dignity. In contexts where oppression erased or prevented official records, his creative practice shows how art itself can stand in for—and even recreate—the archive, reconstructing histories and bringing overlooked perspectives into public view.

Fig. 8. Ilídio Candja Candja (2016), Raízes, mixed media on canvas, 150 x 140 cm.

Fig. 9. Ilídio Candja Candja (2009), Olhando para o passado, mixed media on canvas, 100 x 65 cm.

Restitution between conflict and healing

Through art and research, African artists and their descendants strive to reverse the erasure of silenced historical facts and to propose new narratives for the future (Ribeiro, 2009). Within the historical relationship between Portugal and its former colonies, many comparable cases demand ritual acts of healing and redress, as evidenced in multiple archival records.

With the changing international geopolitical landscape and the rise of global debates regarding heritage restitution and the re-evaluation of colonial histories as shared legacies, new gestures emerge. In 2022, the Municipality of Angra do Heroísmo on Terceira Island, Azores, Portugal, installed a new statue honouring Emperor Gungunhana of Gaza—a symbolic act intended to restore dignity to a once-exiled leader. Yet for decades, his image was belittled in Portuguese popular culture, notably through a ceramic souvenir mug depicting him as drunk and defeated, a caricature born of colonial scorn. The journey from ridicule to public commemoration reveals how social values evolve: what was once an object of humiliation now becomes a subject of official tribute, opening space for more nuanced and equitable narratives about the past.

Moves toward recognition continue elsewhere in Portugal, such as the planned public monument in Lisbon dedicated to the victims of slavery13, and similar initiatives are anticipated in Mozambique, where commemorations could be broadened beyond heroes of the liberation movement to include those who have contributed to freedom in sports, culture, and science. This gradual expansion of public memory reflects the transformative potential of restitution, signaling the possibility of more inclusive and healing approaches to history.

Nota bene: This article has been originally written in Portuguese.

-

UNESCO (1966). Declaration of Principles of International Cultural Co-operation, adopted 4 November 1966, Paris. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/declaration-principles-international-cultural-co-operation ↩

-

DW, "Germany to return looted Benin Bronzes to Nigeria in 2022", Deutsche Welle, April 30, 2021. Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/germany-to-begin-returning-benin-bronzes-in-2022/a-59438275. ↩

-

Duas Linhas (2025, October 6). “Angola Wants to Recover Cultural Heritage Taken by the Portuguese.” Available at: https://duaslinhas.pt/2025/10/angola-quer-recuperar-espolio-cultural-levado-pelos-portugueses/ ↩

-

(Olha)r Moçambique – Percurso Artístico e Cultural nos últimos 50 Anos de Moçambique (Revisiting the Artistic and Cultural Journey of the Last 50 Years) exhibition held at Núcleo de Arte, Maputo, from June to July 2025. The exhibition was organised by a collaborative platform of Maputo-based institutions and cultural practitioners, based on an original concept by Mozambican curator and artist Rafael Mouzinho. ↩

-

This discussion took place during the (Olha)r Moçambique – Revisiting the Artistic and Cultural Journey of the Last 50 Years exhibition at Núcleo de Arte (June–July 2025). Follow-up events featured talks by Marcos Muthewuye on decolonising teacher training and Titos Pelembe on Afrocentricity in Visual Arts Education. Additional debate was held at the Fortress of Maputo, with key contributions from Moisés Timba and Rafael Mouzinho. ↩

-

The Fortress of Maputo, also known as Praça de Nossa Senhora da Conceição, is a national monument reflecting the history of Portuguese colonial presence and local resistance. Originating in the late 18th century as a Portuguese fortification, its current quadrangular, red-stone structure is protected by national heritage law. The building, a replica constructed in 1940 for commemorative purposes, once served as a Military History Museum after independence (source: Fortaleza de Maputo official site). ↩

-

Ngungunhane was the last emperor of the Gaza kingdom, which extended between the Incomati and Zambezi rivers in present-day Mozambique. After independence, the Fortress of Maputo was reinterpreted to honour resistance against Portuguese rule, with Ngungunhane symbolising colonial resistance. His remains rest at the fortress, but his presence as a national hero remains overshadowed by dominant colonial monuments. ↩

-

Interview Mbenga Artes & Reflexões (2019) ‘Bens culturais pilhados nas colónias: devolver África para África’. march 14, 2019. Available at: https://mbengamz.wordpress.com/2019/03/14/bens-culturais-pilhados-nas-colonias-devolver-africa-para-africa/ ↩

-

After the Holocaust, the State of Israel received reparations from the German government, and, in parallel, Jewish survivors received individual compensation directly through organizations such as the Claims Conference. More information available at https://www.claimscon.org/about/history/ ↩

-

The seminar ‘Restitution and Reparation in Post-Conflict Identity: Clean Up the House II’ (2021) was organised by Oficina de História (Mozambique) and Mbenga-Artes e Reflexões.” For further details, see: ↩

-

International touring exhibition curated by Kisito Assangni, presenting African video art and decolonial perspectives. Available at: https://benuri.org/publications/46-still-fighting-ignorance-and-intellectual-perfidy-video-gallery-publication/ ↩

-

Candja Candja, I. (2024) Personal communication. ↩

-

Despite being approved in 2017 and repeatedly confirmed for Ribeira das Naus, the Lisbon Memorial to Enslaved People remains unbuilt as of late 2025. The project has faced technical, bureaucratic, and political delays, including changes of site, disputes between city government and civil society, and contested priorities. ↩

BibliographieBibliography +

Books

Asante, Molefi Kete (1980) Afrocentricity: The Theory of Social Change. Chicago: Amulefi Publishing Company

Atkinson, Dennis (2017) Art, Disobedience, and Ethics: The Adventure of Pedagogy. Cham: Springer International

Costa, Alda (2011) Paths and Perspectives – An Introduction to Art in Mozambique. 2nd edn. Maputo: Escola Portuguesa de Moçambique, Centre for Teaching and Portuguese Language

Costa, Alda (2013) Art in Mozambique: Between Nation-Building and a Borderless World (1932–2004). Lisbon: Verbo

Costa, Alda (2019) Art and Artists in Mozambique: Different Generations and Variants of Modernity. Maputo: Marimbique

Laranjeira, Rui (2006) A Marrabenta: Its Evolution and Stylistic Development, 1950–2002. Maputo: Universidade Eduardo Mondlane

Mbembe, Achille (2014) Critique of Black Reason. Translated by M. Lança. Lisbon: Antígona

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa and Meneses, Maria Paula (eds.) (2009) Epistemologies of the South. Coimbra: Almedina

Savoy, Bénédicte and Sarr, Felwine (2018) The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics. Paris: Ministère de la Culture

Williams, Chancellor (1987) The Destruction of Black Civilization. Chicago: Third World Press

Chapters in Edited Books

Appiah, Kwame Anthony (1995) ‘Why Africa? Why Art?’, in Phillips, T. (ed.) Africa: The Art of a Continent. London: Royal Academy of Arts, pp. 23–33

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty (1988) ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’, in Nelson, Cary. and Grossberg, Lawrence (eds.) Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. London: Macmillan, pp. 271–313

Journal Articles

Cerqueira, Ana Paula. and Severino, José (2022) ‘Cultural Heritage Policy: Observations on Spoliation and Restitution of Cultural Property’, Política Cultural Review, 15(2), pp. 229–249

Institutional Documents

Barroso, Catarina, Borges, Luísa Cabaço and Cabral, Marta (2020) Restitution of Cultural Property – International Framework. Division of Legislative and Parliamentary Information, Assembleia da República, Lisbon. Available at: https://ficheiros.parlamento.pt/DILP/Publicacoes/Temas/75.RestituicaoBensCulturais/75.pdf

Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation – MINEC (2024) ‘History’. Maputo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation. Available at: http://www.minec.gov.mz/index.php/mocambique/historia

Presidency of the Council of Ministers. (2019) Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 42/2019, of 21 February. Diário da República, 1st Series — No. 37 — 21/02/2019, pp. 1390–1392. Available at: https://dre.tretas.org/dre/3624631/resolucao-do-conselho-de-ministros-42-2019-de-21-de-fevereiro

UNESCO. (1966) Declaration of the Principles of International Cultural Cooperation. Paris. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/declaration-principles-international-cultural-co-operation

UNESCO. (1972) Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Paris, 16 November 1972. Available at: https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/

UNIDROIT. (1995) UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects. Rome, 24 June 1995. Available at: https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/cultural-property/1995-convention/

United Nations General Assembly. (1983) Resolution 38/34: Return or restitution of cultural property to the countries of origin. 15 November 1983. Available at: https://research.un.org/en/docs/ga/quick/regular/38

Online Sources

Mbenga Artes & Reflecções (2019) ‘Pillaged Cultural Goods in the Colonies: Returning Africa to Africa’. Available at: https://mbengamz.wordpress.com/2019/03/14/bens-culturais-pilhados-nas-colonias-devolver-africa-para-africa/

Ben Uri (2014) ‘Still Fighting Ignorance and Intellectual Perfidy – Video Art from Africa’. Available at: https://benuri.org/publications/46-still-fighting-ignorance-and-intellectual-perfidy-video-gallery-publication/

Carta de Moçambique (2025) ‘Mozambique Demands Restitution of Looted Artefacts’, 26 May. Available at: https://cartamz.com/sociedade/43343/mocambique-exige-restituicao-de-artefactos-saqueados-durante-o-colonialismo/

Clube de Moçambique (2025) ‘Mozambique: Chissano Advocates “Good Cooperation” and Investments, Not Reparations for the Colonial Past’, 9 June. Available at: https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-chissano-advocates-good-cooperation-and-investments-not-reparations-for-the-colonial-past-

Duas Linhas (2025) ‘Angola Wants to Recover Cultural Heritage Taken by the Portuguese’. Available at: https://duaslinhas.pt/2025/10/angola-quer-recuperar-espolio-cultural-levado-pelos-portugueses/

DW (2021) ‘Germany to Return “Benin Bronzes” to Nigeria’, 30 April. Available at: https://www.dw.com/pt-002/alemanha-vai-devolver-bronzes-do-benim-%C3%A0-nig%C3%A9ria-em-2022/a-57387532

Expresso. (2018). ‘Angola quer as suas bonecas de volta’ [Angola Wants Its Dolls Back]. Available at: https://leitor.expresso.pt/semanario/semanario2406/html/primeiro-caderno/investigacao/angola-quer-as-suas-bonecas-de-volta

Expresso. (2019). ‘Portugal apoia repatriamento de património cultural retirado no contexto colonial’ [Portugal supports repatriation of cultural property removed in the colonial context]. 14 March.

Público. (2019). Governo defende repatriamento de património cultural retirado no contexto colonial [Government defends repatriation of cultural property removed in the colonial context]. 21 March. Available at: https://www.publico.pt/2019/03/21/culturaipsilon/noticia/governo-defende-repatriamento-patrimonio-cultural-retirado-contexto-colonial-1865400

Mbenga Artes & Reflexões (2018) ‘Paulina Chiziane Will Be at the Second Cultural Journalism Seminar’, 7 March. Available at: https://mbengamz.wordpress.com/2018/03/07/paulina-chiziane-estara-no-ii-seminario-de-jornalismo-cultural/

Oficina de História (Moçambique/Mbenga) (2021) ‘Restitution and Reparation in Post-Conflict Identity’, Makanda. Available at: https://restituicao-mocambique-2021.webnode.page/

Ribeiro, A. P. (2009) ‘Próximo Futuro’. Available at: https://proximofuturo.gulbenkian.pt/proximo-futuro

YouTube / AFP (2024) ‘Portuguese President Talks About Colonial Crime’. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NaZTxa5OK4M

Exhibitions and Artistic Events

Franco-Mozambican Cultural Centre. (2024) Magnificence, Light and Fusion II. Exhibition by Ilídio Candja Candja, Maputo, Mozambique.

Mbenga Artes & Reflexões. (2019) Noite de Poesia. Sarau event with Paulina Chiziane, Mozambican-German Cultural Centre, Maputo.

Núcleo de Arte. (2021) Rethinking Arts Education in Mozambique. Roundtable, Maputo, Mozambique.

Núcleo de Arte. (2025). Olha(r) Mozambique: Revisiting the Artistic and Cultural Journey of the Last 50 Years. Exhibition, Maputo, June–July 2025. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/DLSwRVcN8lj/?img_index=16

Still Fighting Ignorance and Intellectual Perfidy: Video Art from Africa. Curated by Kisito Assangni, Ben Uri Gallery and Museum, London, 2014.

This Is Not White Cube Gallery. (2024) Resonance of the Form: Tribute to Sarah Baartman. Solo exhibition by Ilídio Candja Candja, Lisbon.