The emergence of the debate on restitution in Maputo

In early 2019, the question of restitution began to enter into the public sphere in Maputo, making headlines in the cultural press: "Mozambique has not yet taken a position" (Notícias, 17-01-2019); "Cultural assets looted during colonial times—Return Africa to Africa" (Notícias, 21-02-2019); “Restitution is an irreversible process. Portugal must prepare itself” and “It is imperative to restore our humanity” (Notícias, 13-03-2019).

This is how the media brought restitution into the spotlight, framed in formulas heavy with moral and emotional appeal. Presented in this way—as if the return of objects was a straightforward application of justice—crucial practical considerations and broader challenges risked being sidelined. In response to this narrowing of the debate, my colleagues from the Oficina de História (Mozambique)1 and I proposed organising a seminar to open space for wider reflection, enabling the issue to be considered from multiple perspectives and in light of the historical references these processes have generated in Mozambique.

Two young historians from this organization, Ivan Zacarias and Elcídio Macuácua, took the initiative to represent their group by presenting this theme at the annual international conference organized by the Oficina de História (Moçambique). For these researchers, restitution, understood as the most direct form of historical reparation2, emerged as the continuation of the previous year's debate which focused on reparations for the victims of slavery and the condemnation of the injustices produced by the trafficking and exploitation of African populations, discussed during the international colloquium “Memories of Slavery on the Island of Mozambique”3. Since 2015, this academic-cultural group has been coordinating seminars and meetings dedicated to history, archives, heritage, and memory in Mozambique, progressively establishing its relevance in promoting debate and reflection on issues of historical justice and heritage.

Thus, in May 2019, supported by the Franco-Mozambican Cultural Centre (CCFM), Oficina de História (Mozambique) held the first of two seminars dedicated to restitution. The chosen title—"Restitution of Cultural Heritage to Mozambique: History, Reality and Utopia"—signalled the broad and pragmatic approach that the organisation intended to bring to the debate. Yet, the gathering quickly dropped its international dimension—later resumed in the second seminar in 20214—due to financial constraints, opting instead to convene voices from Mozambique only at the CCFM auditorium in Maputo for a full day of debates. Some participants welcomed this circumstance, considering it in fact the timeliest advantage, as it enabled the discussion to be situated and confronted “strictly among ourselves”.

As a Portuguese artist and researcher who has collaborated for several years with this group on archival and audiovisual heritage projects, I was invited to co-organise and moderate one of the debate panels, participating directly in the conceptualisation and realisation of the event. Looking back critically six years later, I return to the records and context of that event to write this article, which I structure as a series of “notes”. This form allows for a multi-layered engagement with the theme at hand. Also, it enables me to weave together official materials from the public sphere of the seminar, insights from the seminar’s backstage preparation, and newer research carried out for an updated understanding of the broader implications arising from those initial conversations.

In the analysis developed throughout this article, I focus on the different meanings that various social actors attributed to restitution, drawing on their contributions to the debate and recognising that these perspectives are shaped by the coexistence of distinct normative systems—national, international and community-based—which influence how restitution is assimilated and interpreted.

The purpose of this article is to provide clear and informative elements that can contribute to the continuation of public debate. It also complements the second seminar of 2021, co-organised by Oficina de História (Moçambique) and Mbenga-Artes e Reflexões, and entitled “Restitution and Reparation in Post-Conflict Identity”. The seminar, held between October and December 2021 in Maputo, brought together national and international experts on cultural heritage, historical memory, and restitution practices in Africa. Its proceedings are publicly accessible online.

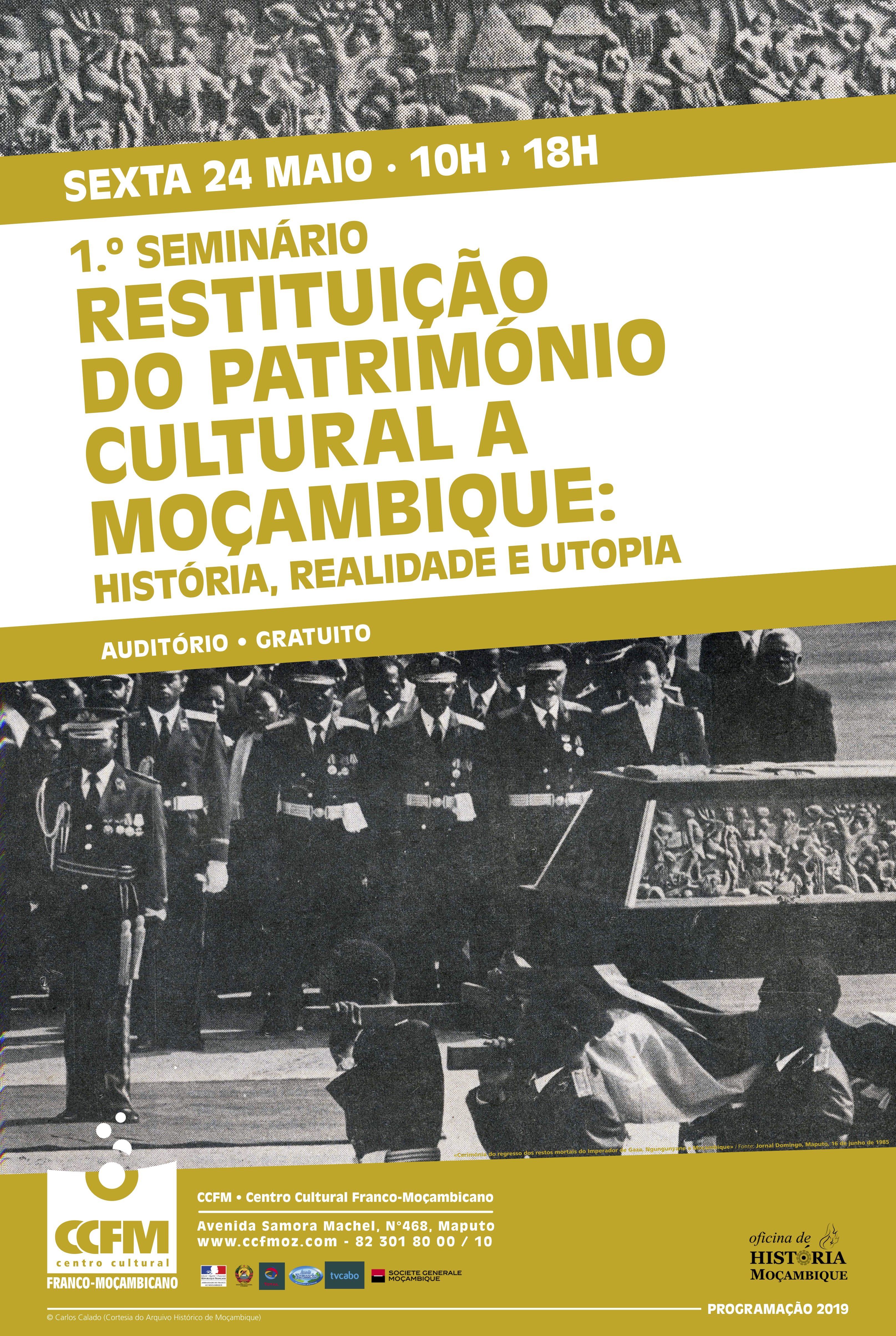

Fig. 1 Poster from 1st Seminar on Restitution of cultural heritage to Mozambique: History, Reality and Utopia", Oficina de História (Moçambique)/CCFM, Maputo 2019.

Note 1. Translation challenges - Framing PALOPS5 in the debate on restitution

The report commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron on African cultural heritage in French museums6 was discussed as one of the pivotal catalysts for the renewed restitution debate and for organising this seminar. Commissioned in March 2018, following Macron’s landmark address in Ouagadougou in November 2017, the report, presented in November 2018, broke new ground by recommending the unconditional return of African artworks taken during colonial rule. This unprecedented stance granted international recognition to the legitimacy of African nations’ claims and exerted significant pressure for ethical and political reform in European museums. Paradoxically, as participants at the Maputo seminar highlighted, this important document that had been celebrated for its reparative intention has never been translated from French into Portuguese. Despite determined and concerted efforts by the seminar organisers, none of the institutions approached (universities and cultural centres) in either Mozambique or Portugal felt they were mandated to undertake the translation of a document7 of such political relevance for the Portuguese-speaking African space (PALOPS). In the face of this and of other sources unavailable in Portuguese, the debate exposed the peculiar Mozambican case, where Portugal’s historic delay in critically confronting its own colonial past perpetuates exclusionary logics for Portuguese-speaking African countries in the international restitution discussion. This lack of translation stands as a tangible indicator, exposing the geo-politically situated constraints of the debate and revealing a continuing disregard for the concerns of African partners8—especially since no representative of Portuguese diplomacy officially attended the event.

Note 2. Core Concepts: Resgate, Restitution, and Heritage (Material and Intangible)

Rather than “restitution”9participants showed a preference for another term, “resgate” (“rescue” or “retrieval”), a notion deeply rooted in Mozambican society. Within the seminar, resgate was used to mean rebuilding destroyed bonds, reconstructing meaning, or simply memory. The term resgate (‘rescue’) is notably used by art historian Alda Costa10 to describe the recovery of African history and culture denied under colonialism, associating it with the affirmation of heritage as a symbol of resistance and national identity in post-independence Mozambique11. In the debate, it was argued that, more than focusing on museum collections, the priority should be to promote a process of reinscribing memory and local power, valuing heritage elements—such as cemeteries, sacred trees, landscapes and ancestral practices—that are contested and undergoing negotiation between communities and the State. This perspective was sharply critical of state centralization. Instead, it proposed a dynamic process where State, community and historically silenced memories engage in dialogue to revitalize endangered identities and bodies of knowledge.

This perspective emerged to varying degrees from the contributions of a diverse group of seminar participants, including writers, historians, cultural managers, artists, researchers, ethnomusicologists, anthropologists, art curators and museologists, representing Mozambican institutions, independent initiatives, and international organisations.

Fig. 2 Paulina Chiziane’s opening session with Elcidio Macuacua and Ivan Zacarias at 1st Seminar on Restitution of cultural heritage to Mozambique: History, Reality and Utopia", Oficina de História (Moçambique) held at CCFM, Maputo on 24 May 2019.

Note 3. The 2019 seminar — Thematic structure, tensions and convergences

The seminar opened with welcoming remarks by Ivan Zacarias and Elcídio Macuácua12 and representatives of the CCFM13. The debate gained significance through the contributions of leading figures in Mozambican history and culture, including the writer Paulina Chiziane14 and cultural historian Matilde Muocha15. Although Luís Bernardo Honwana—a prominent writer, former Minister of Culture, and UNESCO official—was not present at the event, he met with the organisers on 9 May 2019 and offered advice as a consultant, drawing on his experience in Mozambican cultural policy from the 1980s and 1990s.

The seminar brought together representatives of UNESCO and scholars from institutions such as Eduardo Mondlane University (UEM), Nachingwea University (UMA), and the Higher Institute of Arts and Culture (ISArC), as well as professionals from a range of cultural and research bodies—including the National Library, the Socio-Cultural Research Institute (ARPAC), the Mafalala Museum, and the Natural History Museum—alongside informal collaborators, such as Mbenga-Artes e Reflexões.

The discussions were structured into three main parts or “sessions”, each with its own distinct themes, framework, and designated moderators.

1st session–"What does the restitution of Mozambican cultural heritage mean?"

From the outset, speakers made it clear that restitution cannot be reduced to the mere physical return of artworks. As celebrated Mozambican writer Paulina Chiziane stated at the opening, “What is the point of bringing objects back if African dignity, status, and knowledge remain subordinated, neglected, omitted, or even despised in their own land of origin?” For Chiziane, restitution must be understood in its broadest sense: it is the resgate of identity, of symbols, of epistemologies. It means exercising once more the right to narrate, to relearn, to reaffirm everything that that dominant history attempted to silence. It is, above all, a return that goes far beyond the material. Drawing on passages from O Canto dos Escravos (The Song of the Slaves)16 and Ngoma Eto17 she argued passionately that the reconstruction of Africa cannot take place without a recognition of African dignity, religion, traditional medicine, and ancestral knowledge. To restore these legacies is to confront racism and prejudice head-on that, for centuries, have relegated them to the margins. Chiziane was especially forceful in denouncing linguistic racism. She pointed to Portuguese dictionaries where words tied to African culture—such as “curandeiro” (healer) and “palhota” (hut)—are still defined through stereotypes that equate tradition with backwardness or charlatanism. As she put it bluntly: “The very [Portuguese] dictionary we use is racist, it is sexist, it conveys the supremacy of one world over another.”

Later in her address, Paulina Chiziane turned her critique to what she called the logic of “dependent restitution” — the idea that the fate of cultural heritage should rest on the gestures of former colonisers. With sharp irony, she remarked:

I have respect for this white man who finally remembered that stolen things ought to be returned18. But let us ask ourselves: what does the restitution of cultural heritage truly mean? … Are we really to treat these objects as noble treasures simply because they were handed back by a white man who had grown tired of them—like someone gnawing on a bone and, at the end, tossing it aside with a dismissive ‘here, take it, I don’t need it anymore’? And what status shall we then give these works of art?

She reminded the audience of the long history of Africans being systematically excluded as thinking subjects in literature and academia. True restitution, she insisted, can never be a concession bestowed from Europe. It must be defined, claimed, and led by us—Africans ourselves.

The morning moved on with a session devoted to the legality of restitution practices, featuring interventions from UNESCO and the Oficina de História (Mozambique). Speaking on behalf of UNESCO Mozambique, Ofélia da Silva picked up on the position powerfully voiced earlier by Paulina Chiziane: the need to safeguard African leadership rather than submit to external criteria.

She underscored the sovereign character of the restitution process, making it clear that cultural authority lies first and foremost with the nation itself. “It is up to each country to decide what constitutes cultural heritage,” she affirmed. “It is the country that determines which elements embody that heritage. In Mozambique, for instance, we have the Makonde masks. The Makonde people look at them and recognise themselves in them. They hold a special importance.[…] UNESCO does not decide which object or which expression is culturally significant—that decision belongs to the country.”

Ofélia da Silva offered a pointed assessment:

As Chiziane observed, we do not actually know the heritage in our keeping. That’s correct. There is a lack of concrete knowledge about what resides in the Art Museum, the Natural History Museum, the Ethnology Museum, and elsewhere. If any record exists, did it comply with international standards? I am not convinced, because proper compliance would have required collaboration with UNESCO and conformity with convention guidelines, which has simply never happened in our museums. I can say confidently that there is no museum which maintains a register meeting those standards. What UNESCO can do, at the very least, is assist us in compiling an inventory—so we might finally know what the Art Museum contains.

Drawing on this example, da Silva advocated the pressing need for institutional capacity-building and the proper registration and documentation of cultural assets. She emphasised that alignment with major international conventions—The Hague (1954), UNESCO (1970), and UNIDROIT (1995)19—is foundational for the process of restitution. Without ratification, Mozambique risks losing access to technical and legal means for preservation and repatriation: “The secret to restitution, the single most fundamental step, is being a party to the Convention,” she affirmed.

This position brings far-reaching consequences and quickly leads to an impasse. By framing the debate through a legal lens, responsibility is shifted onto the state and multilateral bodies—while the essential contributions of civil society and cultural actors, historically so vital to African restitution processes20, fade into the background.

The morning’s debate began to surface these tensions, exposing the contradictions that arise between the demands for inventory and registration—bureaucratic pillars rooted in Western tradition—and the recognition of intangible heritage, communal practices, and the symbolic layers of collective memory. These dimensions often remain overlooked within formal procedures. Making restitution contingent on future compliance with international conventions risks endless delays and leaves Mozambique in a cycle of external dependence, a paradox given the moral and historical urgency felt by so many present.

Yet, the contributions proved doubly valuable. On one hand, a thorough international legal analysis was brought to the table; on the other, participants offered paths toward a central issue: the need for strategies that democratise the process, opening it up to the plural forms of knowledge and heritage that are essential to the Mozambican agenda.

2nd Session – "Restitution as a struggle for universal justice"

The question first raised in the morning resurfaced with greater detail after the break, as the afternoon panel gathered under the banner “Restitution as a struggle for universal justice.” Historians, anthropologists, and ethnomusicologists from Eduardo Mondlane University (UEM) and Socio-Cultural Research Institute (ARPAC) came together, offering a wealth of perspectives and firsthand accounts on the legacy and significance of restitution.

Anthropologist Marílio Wane21 shared his insights into how colonial-era photography has shaped the process of safeguarding the timbila, a traditional Chopi musical heritage. Reflecting on an archival image from the 1934 Colonial Exhibition in Porto showing Chopi musicians and families encircled by huts with a grand colonial building looming in the background, Wane recounted: “I’ve always used this photograph as a way to spark debate. I’d ask, ‘Where was this photo taken?’… Most would immediately answer, “Zavala”22 …But to everyone’s surprise, I would reveal that the photograph was actually snapped in Porto, Portugal.”

For Wane, this image powerfully illustrates how colonial exhibitions sought to reconstruct the supposed living scenes of the “indigenous” peoples of Portuguese former colonies23.

Wane deepened his analysis, drawing attention to a striking paradox: “What fascinates me about this photograph is how certain cultural elements, captured and catalogued during colonial times, have since acquired renewed meaning and significance as Mozambican heritage.” He noted that the timbila’s international recognition as UNESCO world heritage in 2005 rested heavily on “extensive documentation—documentation that was itself a product of the Portuguese colonial system.”

The urgent task is not simply to passively expose these photographic records, said Wane, but to “critically read colonial photography and contextualise the creation of such documents.” He called the case of the timbila “emblematic”: artefacts once authenticated by the colonial machinery have now been reclaimed as emblems of resistance and national heritage, though the journey has been fraught with silences, ambiguities, and unease reflecting the difficult encounter with colonial memory. He stressed that only in recent years, through sustained academic research in Portuguese archives, has the work of recovering memory gained traction, helping to restore and rebalance critical debate on Mozambican history and heritage:

The moment we present concrete data and evidence concerning the circulation of cultural objects and people, paraded in Portugal as representations of African cultures, we put truly significant information on the table. It is absolutely vital that this knowledge is shared and systematically discussed, with open channels between cultural policymakers in Mozambique and Portugal. Only through such a joint exercise of exchange and critical reflection can we hope to make informed decisions—and discover more powerful ways to respect, tell, and share this history and heritage with the world.

On the same panel, Eduardo Lichuge24, offered a sharp, first-hand critique of the restitution process in Mozambique. Lichuge made clear that, historically, “restitution has often served, above all, institutional, political, and intellectual elites”—those with privileged access to information and decision-making power.“It functions as a banner that legitimises the interests of these elites, rather than as a real return to the communities who first gave rise to these cultures… The genuine meaning of restitution will only be realised when it truly involves those communities.”

Lichuge illustrated this through the practice of timbila, highlighting its collective and identity-based logic: “By tradition and custom, timbila must be played together—twelve, fifteen, twenty, or even thirty members. That is what we call Ngodo25. Yet, I see it has been cut out, and many today do not even know what Ngodo means.” He emphasised it refers to the “trunk”—the heart of musical and ritual practice—and warned that removing the instrument from its context is “to cut the body from the process”. Drawing on experience with museum inventories, which often reduce timbila to just another “object”, stripped of ritual, memory and living function among the Chopi, Lichuge provided a powerful critique: “The inventory has been used to classify and subordinate cultural forms under external rules, erasing the Ngodo from official accounts and making the richness of performance and memory invisible… What we’re left with is a fragment, and that echoes what’s happening today. We look at the inventory and it might give us identity if the instrument is linked to a place—but if identity is understood only in the instrument, we have mutilated the experience. I would always rather see the instrument in its full context, because only then does it find its true meaning.”

Next, museologist Kátia Filipe26 brought a pragmatic perspective to the debate, urging those working in heritage to focus on the practicalities of access and preservation for future generations. In a subtle critique of more simplistic viewpoints, she argued: “I agree that works should be kept where they can best be preserved—that’s a positive step. But what happens, in practice, is that when we lack access to certain pieces or documents, we’re not even aware of their existence. Others end up with the relics that belong to us, while we in Mozambique remain unaware of what’s out there. We have to fight, absolutely, for things to be cared for properly. But that cannot mean surrendering them so easily.”

To ground these reflections, Filipe recalled the national campaign for cultural preservation from 1979 to 1983 in which she participated, describing it as a pivotal episode for Mozambican memory. She pressed for self-examination: “What have we really put in place since then, enabling us to debate repatriation with full knowledge? Before investing in infrastructure, or in parallel, we must complete the inventory still pending, the part that’s missing.”27

When challenged by an audience member about how to restore an “interrupted cultural process,” and how such idea could be translated into policy, Filipe replied:

Restoring cultural processes is as vital as repatriating physical works of art. It means shaping policies and practices that revive and continue customs, knowledge, and expressions interrupted by colonialism—through education, research, and active community involvement. But this conversation demands deep reflection: Mozambique is still searching for its sense of self. Rather than just dwelling on what’s lost, we are called to design policies that answer the colonial legacy and reassess the interests that have hardened within it. As Eduardo [Lichuge] remarked earlier, it is complex to discuss heritage when we are still asking who we are, and what we want to become.

Replying again to concerns about inventories, Filipe advocated a critical engagement with their history and the routes taken by displaced heritage: “What we cannot do is deny history. We cannot pretend that objects weren’t removed under certain circumstances. But now, we have an opportunity—to tell a new story, or tell the history of an object, even from the object’s perspective itself.” In this way, Kátia Filipe reinforced the importance of examining and mapping the displacement of heritage, essential groundwork for any meaningful debate on repatriation.

The closing panel managed to lay bare, through a single resonant image, the violence of “the cut”—the fragmentation that occurs when technique is separated from context and community—highlighting the flaws of the current heritage model. Concrete avenues for broader participation and co-authorship—alternative to purely academic critiques—remained frustratingly faint. They were only hinted at in tentative proposals.

Nevertheless, the call for education, training, and renewed debate saw the voices of public and participants alike converge, even in the stark absence of government or political figures prepared to champion educational renewal of Mozambican heritage.

3rd Session – "The Possibility of reinventing the museum"

The seminar’s final session posed a challenging question: can the museum reinvent itself, transcend the constraints inherited from colonial structures, and become a real agent of social transformation in Mozambique? To shed light, the panellists, artists, and curators turned to their own concrete experience. The session opened with the unfolding story of the then soon-to-open

Mafalala Museum28. Mafalala is the birthplace of many leading figures in Mozambican culture, politics, and sport—including Samora Machel, Joaquim Chissano, Eusébio, José Craveirinha, Noémia de Sousa, and Fany Mpfumo—and it has been the backdrop for pivotal episodes in Mozambique’s national identity. Yet, the neighbourhood is still marked by poverty and chronic lack of infrastructure, factors that continue to devalue its rich heritage, both cultural and human.

Ivan Laranjeira29, curator and director of the Mafalala Museum, shared the experience of creating Mozambique’s first community museum: “Mafalala needs to be restituted. To restitute means to restore value both to the people and to the memories contained within this space… It’s about feeling with pride, ‘I am from Mafalala,’ and about putting actions in place that transform how the neighbourhood is perceived.” Rather than reproducing the tradition of colonial centralisation, the Mafalala Museum aims to value the territory itself, the lived stories, the multitude of voices and the vibrant community dynamics.

The next discussion turned to South African models, acknowledging how the post-apartheid experience had inspired change—museums like the Apartheid Museum have become spaces for living memory and mediation between complex historical identities. Yet, panellists from the arts highlighted unresolved contradictions: “In South Africa, the promises of decolonisation run up against the realities of the international art market, monopolised archives, and narratives still dominated by old powers”. Examples surfaced — the repatriation of Sara Baartman, the fraught rhetoric of reconciliation, persistent social struggles, and “the enduring racial hierarchies that shape institutions, even after Apartheid.”

Marion Duffin30, a British museologist living and working in Mozambique, was blunt in her critique: “The British Museum, by rebranding itself as ‘universal’, has only tightened its grip on African heritage. It is a cynical move that delays restitution and turns it into a mere political game”. The concern echoed among speakers and the audience alike: “If we lack the means to receive these objects, should we not begin the debate by empowering local museums and archives, so they are ready in the future? Mozambique is not prepared, but how will we ever be, if the objects never return and no one invests?”. Audience contributions laid bare both the practical and political challenges, referencing the Benin bronzes as an emblem of the role museums play in the retention of the colonial empire’s legacy, both materially and symbolically.

Rafael Mouzinho31, an artist and curator, called for artistic practices to step up, embracing their potential as agents of symbolic and narrative restitution: “Artists should not simply follow the mainstream. Our job is to recover stories, bring hard questions into the conversation, and refuse submission to colonial curatorial agendas.” Visual artist and teacher Félix Mula32 added: “The international circuit legitimises only a minority, repeats Eurocentric logic, and keeps reproducing a narrative in which ‘to be African’ is always to be the outsider, the exotic.”

The panel reached a clear consensus: reinventing the museum will require commitment at all levels, decentralised action, and, above all, significant investment in Mozambique’s own memories and heritage. The lesson from South Africa still resonates: true transformation is driven from within, with local voices leading the way as Laranjeira affirmed in closing.

Note 4. Luís Bernardo Honwana at the National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon

During his visit to the Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon in the mid-1980s, Luís Bernardo Honwana33, then Secretary of State for Culture of Mozambique, encountered collections of Makonde art, musical instruments and other cultural objects meticulously hidden from public view—the legacy of colonial collecting and a museology more invested in study than in sharing34. He discovered “pieces that he never even suspected existed” including objects that had long faded from Mozambican memory, like the rare bass from the timbila orchestra: “I saw an instrument that was a timbila, but it was totally different from the timbilas I knew… the memory of this instrument had been lost.”

Moved by this, Honwana suggested to Margot Dias35, who was responsible for the collection, the organisation of an exhibition in Mozambique, expressing his wish to restore the communities’ connection with their heritage: “But wouldn’t it be possible for you to organise an exhibition… Because these are not just museum pieces. I mean, some of these instruments, there are people who still know how to play them, who still know how to tune them.”

Honwana recognised Portugal’s hesitance in tackling issues around restitution and colonial history. “At the time [1983-1985], Portugal agreed to return Ngungunhane’s remains36, yet there seemed no willingness at all to display or repatriate Mozambican cultural artefacts held in Portuguese museums.” Looting and the colonial past were topics best left undiscussed: “No mention of theft, no mention of the colonial past, no mention of all these things that [for Portugal] are still not so easily spoken about.” Dias was cordial, but her hesitation and discomfort signalled the limits of deeper collaboration.

When the initiative stalled, the focus shifted to borrowing Makonde art pieces from various international museums. Yet insurance requirements for transporting objects to a war-torn Mozambique made an exhibition impossible: “Astronomical sums appeared… The collectors and museums identified in Europe and Asia asked for insurance agencies to intervene before any further conversation. The cost came close to Mozambique’s state budget at the time. All this just to see what is ours, from Mozambique… this heritage, well, their heritage, naturally.”

This failed project illuminated the paradox of ownership: what is known in Mozambique as “ours” is, by the rules of history and international law, defined as “their heritage,” under the authority of European museums and state institutions. The issue is not only one of physical possession or location, but of historical, legal, and political codification—the designation of heritage depends on those empowered to declare it, guard it, and set the rules for its circulation and access.

Barriers to restitution are woven into these regulatory devices, legacies of colonialism that decide who is entitled to determine the fate of the objects, leaving Mozambique dependent on records, inventories, and formal criteria imposed by Europe. Honwana summed up the situation starkly: “There will be no exhibition of Makonde art in Mozambique… But at least we want to hold an exhibition in a European country.” The exhibition that was ultimately held was Art Makondé: Tradition and Modernity [Art makondé : tradition et modernité], organized in Paris at the Musée des Arts africains et océaniens, from November 1989 to January 1990, under international curatorship37, showcasing the greatest Mozambican sculptors.

Honwana recognised that the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue38 did succeed in bringing much-needed visibility to Makonde art held abroad. Yet, he lamented the lack of meaningful follow-through within Mozambique itself: “All of this lacked real continuity at home, for at the heart of it, the main aim should have been…to reconstitute in Mozambique the cultural and artistic processes interrupted by the removal of these pieces.”

Financial, political, and historical barriers make it plain that access to heritage is never a neutral issue—it “touches on deep disputes over recognition and power over memory.” In the final analysis, restitution is not merely a bureaucratic or logistical concern; it is a matter of dignity, self-determination, symbolic power, and the right to make decisions over heritage and the foundations of history and culture themselves.

Note 5. Ngungunhane - The returning story

The seminar poster honoured Ngungunhane (c. 1850–1906), last emperor of the Gaza State in southern Mozambique. Today, the return of Ngungunhane’s remains is widely remembered as a foundational act of historical restitution in the country. Between 1983 and 1985, Mozambique’s president, Samora Machel, negotiated with Portuguese president, General Ramalho Eanes, for the return of Ngungunhane’s remains, the renowned African leader captured by the Portuguese colonial army in 1895.

In the post-independence national narrative, Ngungunhane became mythologised as a hero of anti-colonial resistance, though, locally, memories of his reign are more ambivalent39, shaped as much by stories of dominance and violence over other chiefdoms as by accounts of opposition to colonial rule. Following his capture at Chaimite, Portuguese propaganda transformed Ngungunhane’s downfall into a symbol of colonial victory: he was held up as a major military prize, a sign of the “conquest of Africa” through the defeat of a storied African ruler. In exile, he was forced to adopt a new life—taught to read, converted to Catholicism, removed to the Azores, and eventually dying far from his homeland and ancestral traditions in 1906.

In Mozambique, controversy surrounding the capture and the return of Ngungunhane’s remains has intensified over time. The ceremonial handover of his remains—negotiated between Samora Machel and the Portuguese government in Lisbon—was later described by Portugal’s ambassador José César Paulouro das Neves as “marking a new era in our shared relationship,” and intended as a diplomatic gesture to compensate for stalled economic negotiations. Political and economic cooperation remained unresolved; as the ambassador observed, “a long-anticipated credit line could not be agreed.” Thus, almost by chance, the return of Ngungunhane’s urn became a gesture of "rapprochement" and the centrepiece of Mozambique’s tenth-anniversary celebrations.

Over time, the return of Ngungunhane’s remains came to symbolise the larger, difficult process of reconciling with the former coloniser. The story remains highly contested, but is ever-present—referenced in Mozambican literature, cinema, visual art, and public debate around memory and heritage. Works such as Ualalapi by Ungulani Ba Ka Khosa, The Bones of Gungunhana by Marcelo Panguana, and The Emperor’s Sands by Mia Couto40 have each challenged the standard heroic narrative, showing Ngungunhane at times as a tyrant, at others as a tragic figure destroyed by exile. This diversity of narratives—woven through fiction, schoolbooks, journalism, and oral tradition—sustains an ambiguous but compelling portrait of the last emperor of Gaza, one marked by both controversy and deep resonance in Mozambican memory.

Note 6. One poster for two friezes

The seminar poster’s central image, taken at the 15 June 1985 ceremony41, records the return of Ngungunhane’s supposed remains to Maputo—a diplomatic gesture orchestrated by the political elite. The top frieze of the poster displays a close-up of the jambirre urn, itself a bas-relief featuring scenes inspired by the history of resistance and Mozambican popular imagination. Yet a “frieze” more central still is the photographic band showing the Frelimo ruling elite assembled together, side by side.

This use of the monumental procession as poster imagery sparked informal commentary among seminar participants, overheard during breaks: “Restitution will only happen after those people are no longer here.” There is a strong public perception that the greatest barriers to restitution today are not solely technical or diplomatic but are fundamentally “internal”—rooted in the political, generational, and institutional realities embodied by the historic Frelimo leadership. These figures have become, in the public imagination, a symbolic bulwark against genuine transformation and institutional renewal.

Despite the effort to monumentalise Ngungunhane’s legacy, the act of “restitution” left open a wound: the urn did not contain authenticated remains but only symbolic soil from Angra do Heroísmo in the Azores. The real remains of Ngungunhane remained lost—until, finally, in December 2024, a team of Azorean historians located documents42 that enabled them to pinpoint the true location of his grave. Even so, the original gesture remains in question; in Portugal, Ngungunhane is still commemorated in popular narrative, schoolbooks, and museum displays as the defeated43, the “vanquished” (“o Vencido”), his story seldom accompanied by a meaningful critique of colonialism or acknowledgment of historical injustice.

By bringing together both the urn and the assembled elite, the poster itself became a catalyst for debate—exposing the many layers, barriers and concentrations of power that continue to mediate (and, at times, obstruct) the process of cultural restitution in Mozambique.

In her closing remarks, professor Matilde Muocha44, a prominent researcher in heritage studies, handed this same challenge back to the audience, encouraging a moment of shared public reflection—a gesture that mirrored the depth and disquiet which the day’s discussions had provoked:

I confess this will not be an easy task, for today’s proceedings have been rather like reading a book that captivates us in its early pages. In the moments that will follow, we’ll hardly wish to speak to anyone, or to form an opinion—indeed, as is often said, we feel we must ‘sleep on it’. The subject lingers in the mind…Before discussing restitution, I invite you all to consider how, through our history, we have created the idea of nationhood; what processes have shaped our identities, and how we understand our heritage and our collective memory today. Do we truly know this history? What does it mean, for each of us and for the generations to come, to open up the conversation on restitution in Mozambique?

Note 7. Matilde Muocha's final remarks

Matilde Muocha began by drawing together the central threads of the discussion, stressing foundational concepts and the need for clarity. From this basis, she moved beyond mere summary, devoting most of her speech to a topic that set her intervention apart from those preceding: a thematic progression from theoretical critique and intellectual self-examination to concrete political analysis.

Throughout the debates, words like “deconstruction,” “coloniality,” and “post-coloniality” reverberated—terms demanding what she called “terminological and conceptual clarity”: not slogans, not vague theory, but a daily discipline—knowing what is being spoken of, naming lived realities, keeping words clear and precise. “It may seem minor,” she insisted, “but it is not.” For Muocha, theoretical critique must always be partnered with self-critique; in Mozambique, knowledge is never produced on neutral ground, for every field—from academia to curation to art—is “intersected by the direct consequences of colonialism.” The problem of subalternity, the uncritical adoption of foreign models, the endless fight for legitimacy—there is always the risk of retelling the story in another’s voice or of excessively sanctifying the national narrative. Both call for rigorous deconstruction: not simply dismantling the world of the former coloniser, but unravelling the metanarrative that shapes Mozambican identity, and situating this process as ongoing and contextually rooted.

In a key moment, she singled out the “danger of producing new forms of subalternity and the reproduction of centralism,” challenging the continuing dominance of Maputo at the heart of the debate on restitution, and pointing to the ways this hegemony perpetuates exclusion and the invisibility of experiences from other provinces.

Invoking thinkers like Gayatri Spivak, Muocha called for self-critique among Mozambican intellectuals: those who lead debate can also, unwittingly, renew forms of exclusion, recreate subalternities, or seek comfort in the role of spokesperson “continuing to speak on behalf of the subaltern” while remaining at a remove from community recognition and involvement.

On the subject of terminology, she critiqued the automatic importation of Western systems and categories—such as the Heritage Law (Law 10-88)—and highlighted the practical challenge of translation: in Xangana, for example, “Ntumbuluko” does not separate “culture” from “cultural heritage”. Real restitution, she argued, must start with acknowledging local ways of naming and valuing heritage.

At the heart of her speech lay the shift from legalistic and technical self-reflection to the arena of symbolic and political struggle. She pressed the urgency of redefining the very concept of restitution—who it serves, and who gives it legitimacy: “Legal? Not enough. Technical? Not enough either. Restitution is a symbolic dispute.” She concluded that Mozambique’s post-colonial condition binds restitution to sociopolitical dynamics: “We cannot speak of cultural heritage or collective memories without the intervention of political power.” The greatest challenge does not lie simply in recoverable artefacts, legality, or technical hierarchies, but runs through power relations: What identities and memories make up Mozambican society? Who has the authority to represent them? Who decides what will be returned, to whom, and under what terms? Because these processes are central to shaping national narratives and identities, they are inevitably subject to political context and influence. Heritage inherited in Mozambique is heritage contested by power; every decision is political, every return part of the ongoing inscription of history—a battle of legitimacies. It falls, necessarily, to the state and public leaders to define and manage this history, memory, and cultural heritage in the public sphere.

Muocha grounded her analysis in a concept she named “informative silence.” The silence hanging over restitution issues is not empty; it is a kind of pact. Portugal and Mozambique have tended to avoid open conflict, using what remains unsaid as strategy. She expressed concern: “This silence must tell us something…“We do not wish to speak of it. The time is not right; we are uninterested, uninclined…” She argued that such institutional and strategic silences generate consensus and block progress, preventing genuinely plural forms of knowledge and memory from entering the public domain.

In closing, Muocha allowed space for doubt about the real impact of returns. Without tangible conditions for public engagement, infrastructure, and catalogues, she questioned whether the mere act of giving heritage back could end up reaffirming, rather than overcoming, colonial logics. She cited a compelling example: while visiting the University of Coimbra, she saw an object formerly used in traditional medicine and ritual, catalogued in the museum simply as a “fly swatter”—one more case of decontextualisation, where “objects, once removed from their worlds, are boxed out.” Here, she insisted, it is not only the object that is lost but also “meaning, narrative, and dignity—cut from both objects and peoples.” Drawing inspiration from Paulina Chiziane, Matilde Muocha concluded with a challenge for resgate: more than returning what was lost, Mozambique must break the cycle of “cultural self-denial,” and restore meaning, legitimacy, and narrative to its own heritage—bringing communities back into the heart of naming and telling their own stories.

Note 8. Restitution and Memory Governance: Interim Conclusions

On 9 June 2025, Mozambique’s Minister of Culture, Samaria Tovela, responding to international appeals, publicly advocated for historical reparations and the restitution of heritage removed during colonialism. Speaking during Africa Day celebrations in Maputo, she declared: “Today we are free, but we need to recover all that was stolen from the African continent. That’s why the theme for Africa Day this year is ‘Justice for Africans and for people of African descent through reparations’” Tovela called for African unity and for the development of coordinated policies to guarantee justice and the recovery of material and symbolic legacies45.

However, soon afterwards, Joaquim Chissano, former President and influential Frelimo leader, publicly reasserted the government’s established line, stating: “good cooperation and investment, not reparations for the colonial past,” 46 thus distancing himself from Tovela’s call for direct restitution and historical redress.

This episode underscores, yet again, the recurrence identified during the first restitution seminar: silence and absence—whether of objects, open recognition, or inclusive debate—still actively shape Mozambique’s public space, outlining areas of tension and the boundaries of what is possible.

The public disavowal of a sitting minister by the party's historic leadership exposes how these absences are both produced and sustained by informal modes of governance, leaving the structural incompleteness of collective memory unresolved. Especially in times of crisis, decisions are typically made through personalised authority rather than by transparent, institutional means. This ambiguity is hardly new; diplomatic reports from the 1980s by Paulouro das Neves already noted the careful balance sought between pragmatic cooperation with Portugal—favoured by a more progressive, pro-Portugal faction within Frelimo—and resistance to such engagement coming from a more radical wing of the party. Historic moments—like the return of Ngungunhane’s ashes or contemporary debates on cultural restitution—show that even in the face of potent symbolic pressure, political preference in Mozambique has often leaned towards stability and tangible benefit rather than forceful historical demands.

The 2025 episode fits this established pattern, reinforcing the predominance of moderate voices in shaping memory policy and limiting opportunities for open contestation. Thus, restitution—whether pursued or avoided—remains a key site for debating who has the right to narrate, negotiate, and legitimise Mozambique’s past. Yet, by raising the issues of restitution and redress so publicly, the minister signals that the debate remains open and still central to the national agenda, sustaining the possibility of ongoing transformation within this volatile political space.

Fig. 3 Still from GifMeBack#, © Catarina Simão (2022), after Marílio Wane’s Ngonani mu ta wona [Exhibition, 2021]. Collaborative digital project on colonial archives and restitution. More here.

Afterword: Beyond restitution – critical reflections

In Mozambique, this debate initiated by the three sessions of the seminary made clear that restitution could indeed be a first step towards historical justice and international recognition of Mozambican sovereignty over its heritage and memory, encompassing both material objects and intangible cultural values. Yet, the Mozambican context shows the necessity to widen the understanding of restitution, as does the term resgate—that points to epistemological, historical and social revisions. The recovery of narrative autonomy by actors in Mozambique and on the African continent is a crucial element of this process. Participants stressed the need to think of both dimensions simultaneously, so that any action regarding cultural heritage might produce a structuring and lasting effect, rather than merely resolve museum concerns or take part in diplomatic agendas.

For some participants, such an approach was linked to a more demanding process of decolonization, since it sought the full reconstruction—material, symbolic and subjective—of what was lost or destroyed. For others, turning to the notion of resgate was a cautious detour around the many hindrances of formal restitution. These obstacles included the likely exclusion of communities from formal proceedings, Mozambique’s limited technical capacity and infrastructure, legal and bureaucratic barriers, the absence of open dialogue with Portugal—a country lagging behind other European former empires in this field—along with a general lack of confidence that the Mozambican State would take ownership of the heritage to be restituted.

It was emphasised that in Mozambique, the pursuit of historical reparation runs through everyday life—that is not confined to a formal act, but lived as an ongoing practice of experience, appropriation, and the continuous reconstruction of identities. Heritage here is conceived as a living process, devoted to the reintegration of memories and the collective recognition of belonging—a notion that challenges the established social role of national museums and archives. The idea of resgate places value on community initiative and the active involvement of those concerned, in contrast to formal restitution which remains bound to legal procedures, international agreements, ratified conventions, and state-to-state recognition. The latter is hostage, above all, to political agendas, diplomacy, and the technical-legal apparatus that underpins them.

The first seminar brought to light a strong collective aspiration for the affirmation of identity. Dialogue and co-construction were consistently highlighted as central to this shared, day-to-day process, which concentrated especially on the valorisation of intangible heritage. From this perspective, historical reparation is not restricted to the colonial period under Portuguese or other European rule. Rather, it embraces all enduring forms of violence in society, understood as colonial legacies that have been reshaped into the contemporary structures and threats persisting in post-independence life.

This article has been originally written in Portuguese.

-

The Oficina de História (Moçambique) is a self-organised academic-cultural movement launched in Maputo in 2015 by students and early-career researchers from Universidade Eduardo Mondlane (UEM) and Universidade Pedagógica (UP). The name “Oficina” (workshop) signals international and collaborative inspiration, prioritising peer exchange and debate rather than direct continuity with the 1980s “Oficina de História” linked to Centro de Estudos Africanos (CEA-UEM), though both share a commitment to innovative Mozambican historiography. ↩

-

They referred to the material return of goods or heritage unjustly appropriated in the past (such as works of art, artefacts or human remains), rather than merely acknowledging the injustice symbolically or apologising. This approach has been advocated by authors such as Bénédicte Savoy, Felwine Sarr, Achille Mbembe, Carlos Serrano Ferreira and, in earlier times, Cheikh Anta Diop, among others. ↩

-

The international colloquium "Memories of Slavery on the Island of Mozambique: History, Resistance, Freedom and Heritage" was held in August 2018 on the Island of Mozambique, on the initiative of Oficina de História (Mozambique), in partnership with UNESCO and various national and international academic institutions, as part of the celebrations of the city's 200th anniversary and the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade. ↩

-

The international seminar “Restitution and Reparation in Post-Conflict Identity” was organized by Oficina de História (Moçambique) and Mbenga-Artes e Reflexões, in Maputo and online, from October to December 2021. The event brought together participants from Mozambique, South Africa, Kenya, Senegal, France, and Portugal, and received support from institutions such as the Centro Cultural Franco-Moçambicano, Centro Cultural Moçambicano-Alemão, Goethe Institut Kenya, Africa No Filter, Raise Up! Mozambique (GoFund), Centro Português de Fotografia, Arquivo Municipal do Porto, and Torre do Tombo (Lisbon). ↩

-

PALOPS is the acronym for "African Countries with Portuguese as an Official Language". PALOPS identifies Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique and São Tomé and Príncipe as African countries which, after convergent anti-colonial struggles, maintain Portuguese as their official language and engage in joint political and diplomatic cooperation. ↩

-

This refers to the “Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain. Vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle” (2018) prepared by Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr. ↩

-

The seminar organisers received free authorisation from the editors and authors to translate the report. Given the refusal from institutions, a Mozambican translator was commissioned to translate the first chapter, with the cost covered by the organisers. This material was distributed to participants in advance. ↩

-

African partners refer primarily to African states, cultural institutions, and communities directly engaged in restitution processes and negotiations regarding cultural heritage. Recognition of these partners is principally required from former colonial powers and international organisations responsible for convening or mediating restitution discussions, emphasising the necessity of their genuine inclusion and representation in diplomatic and cultural forums. See, for example, UNESCO materials on African cultural restitution and reports addressing diplomatic dynamics in restitution. ↩

-

In the post-colonial context, it commonly refers to the physical return of cultural property, works of art or historical artefacts to their country or community of origin, after they have been removed — through looting, trade or colonial transfer — to museums, private collections or institutions in the global North. ↩

-

See: Alda Costa, “Notes on Museums, Exhibitions and Discourses of National Exaltation in Mozambique,” eBooks from the University of Minho, 2007. Available at: ↩

-

For complementary and alternative approaches to memory practices, heritage, and identity—particularly those emphasising oral history, community memory, and decoloniality—see works by Luis Bernardo Honwana, Rui Mateus Pedro, José Forjaz, Rui Lopes, Ana Maria Mão-de-Ferro and Yussuf Adam. ↩

-

Zacarias and Macuácua, de Oficina de História (Mozambique), took on the organisation of the event and the moderation of some of the debate sessions. ↩

-

The Franco-Mozambican Cultural Centre (CCFM) was the main institutional and logistical partner of the seminar, providing the venue for the meeting in its auditorium, although the organisation and initiative for the event belonged to Oficina de História (Mozambique). This note is intended to counteract the tendency to overestimate the role of the CCFM in organising this seminar in official ICOM - Mozambique press releases. ↩

-

Paulina Chiziane, one of Mozambique's most renowned authors, was recognised as the first woman in the country to publish a novel after independence. Her work addresses issues of identity, post-colonialism and the relationship between tradition and modernity, and she is an essential voice on the themes of memory and cultural heritage. ↩

-

Matilde Muocha is a historian and researcher at the Higher Institute of Arts and Culture of Mozambique (ISArC), whose work focuses on heritage and memory in contemporary contexts. ↩

-

Paulina Chiziane, O Canto dos Escravos (The Song of the Slaves). Maputo: Ndjira, 2017. ↩

-

Paulina Chiziane, Ngoma Eto. Maputo: Ndjira, 2015. ↩

-

Paulina Chiziane refers here to French President Emmanuel Macron, who in 2017 publicly announced his intention to return African heritage held in French museums that had been looted during the colonial era. ↩

-

Ofélia da Silva refers to the main international conventions on the protection and restitution of cultural property: The Hague (1954) addresses the protection of heritage in armed conflict; the UNESCO Convention (1970)—which Mozambique has not ratified, despite advocacy efforts in recent years—regulates the prevention of illicit trafficking and the return of cultural property; and the UNIDROIT Convention (1995) establishes legal mechanisms for the return of stolen or illegally exported cultural objects. ↩

-

Cf. UNESCO. “New forms of agreements and cooperation in the area of return and restitution of cultural property in Africa.” Regional Dialogue, Addis Ababa, 2025. The report acknowledges tensions between state centrality and civil society participation, suggesting collaborative arrangements to overcome the impasse and promote more inclusive processes. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/new-types-cooperation-and-agreements-field-return-and-restitution-cultural-property-africa ↩

-

Recognised for his contributions to anthropological research and Mozambican cultural heritage, Marílio Wane presented his perspective through a video interview broadcast during the seminar. In the interview, he refers to his master's thesis, carried out at the Federal University of Bahia, and to his book Timbila Tathu: cultural policy and identity construction in Mozambique (Maputo: Khuzula, 2018). the book that derives from that work, addressing the timbila, an emblematic musical instrument and Mozambican cultural heritage. ↩

-

Zavala is a district in the province of Inhambane, recognised nationally and internationally as the main birthplace and centre of production of timbila orchestras, an emblematic musical instrument of the Chopi people in Mozambique. ↩

-

On these occasions, in addition to the objectification of the instrument, Chopi musicians were also presented in reconstructed settings as an authentic "human zoo," projecting an image of Mozambique and its cultures selected by the regime. ↩

-

Eduardo Lichuge is a Mozambican ethnomusicologist, lecturer and researcher, teaches at School of Communication and Arts at Eduardo Mondlane University (ECA-UEM). Among his main works are the article "The timbila of Mozambique in the concert of nations" (Locus: Revista de História, vol. 26, no. 2, 2020, pp. 261-290) and the doctoral thesis "History, memory and coloniality: analysis and critical reinterpretation of historical and archival sources on music in Mozambique" (University of Aveiro, 2016). ↩

-

The spelling “Ngodo” was chosen as used by Marílio Wane in Timbila Tathu: cultural policy and identity construction in Mozambique. ↩

-

Filipe is a lecturer at Eduardo Mondlane University and, since 2022, Director of the Department of Culture. With over twenty years of experience in the field of heritage, she has developed research and practice in inventory, preservation and training, focusing on promoting public access and critical analysis of heritage policies in Mozambique. ↩

-

Between 1979 and 1983, Mozambique carried out a national campaign to collect, preserve, and promote cultural collections. The multi-year process of inventory and documentation ultimately resulted in the publication of Campanha Nacional de Preservação e Valorização Cultural (1979–1983): Volume I: Organização da Campanha & Exploração mineira e Trabalho com metais. Maputo: Fundo Bibliográfico da Língua Portuguesa (FBLP), 2023. Volume II: A Aldeia Tradicional. Maputo: FBLP, 2024. Volume III: Habitação Tradicional. Maputo: FBLP, 2025. ↩

-

The Mafalala Museum is not the first museum created in Mozambique after independence but it is recognised as the country's first community museum. Founded through the work of the IVERCA Association, it opened in June 2019 in the Mafalala neighbourhood of Maputo, with the aim of preserving and promoting local culture, history and memory through participatory initiatives by the community itself. ↩

-

Ivan Laranjeira is a curator, cultural producer and director of the Mafalala Museum in Maputo, founder of the IVERCA Association, working to promote Mozambican heritage. ↩

-

Marion Duffin is a consultant for the Maputo Museum of Natural History, bringing extensive experience from museums in the United Kingdom. During the Maputo seminar, she took a critical stance towards the European perspective on restitution and encouraged increased collaboration between African and European museums. ↩

-

Active on the national and international scene, Rafael Mouzinho develops projects related to the promotion of contemporary heritage and new perspectives on historical memory. He is currently assistant curator at the Eduardo Mondlane University Art Collection and a lecturer in curatorship. ↩

-

His practice focuses on photography and installations about memory and identity. He has won awards and exhibited regularly in Mozambique and internationally. ↩

-

He participated in MONDIACULT/1982 in Mexico, where he witnessed the international debate on the restitution of heritage, marked by the case of the Parthenon marbles and French Minister Jacques Lang's denunciation of the illegitimacy of European museums retaining pieces obtained through looting. ↩

-

In the mid-1980s, the National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon was mostly closed to the public, functioning primarily as a research center; its collections were accessible only to researchers or in exceptional cases. ↩

-

The relationship between Luís Bernardo Honwana and Margot Dias was consolidated during his visit to the National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon in the mid-1980s. Honwana came into contact with collections of Makonde art assembled by Margot and Jorge Dias during the “Portuguese Overseas Ethnic Minority Study Missions” (1957-1961). Margot Dias, a researcher and filmmaker who pioneered the use of ethnographic film in Portugal, was responsible for documenting Makonde musical practices, traditional technologies and rituals, forming one of most well-known collections on Mozambique in the history of Portuguese anthropology. ↩

-

Portugal was then preparing the return of the remains of Ngungunhane, the last emperor of Gaza, who was exiled to the Azores after his capture in 1895. Negotiations and official ceremonies were taking place, symbolising diplomatic rapprochement and evoking the importance of historical memory for Mozambique. ↩

-

In institutional terms, the exhibition was organised by a collective curatorship, bringing together the Mozambican Ministry of Culture, a Mozambican committee (Alta Costa, Paulo Soares, Carlos de Carvalho, Ana Elisa Santana Afonso), French, German and Tanzanian experts, and international support, mainly from France, with the aim of presenting a representative sample of Makonde art. ↩

-

The exhibition catalogue Art Makondé: tradition et modernité, Paris, Association française d'action artistique, Ministère des affaires étrangères, Musée national des arts africains et océaniens, 1989. The 209-page-volume, with texts in French and Portuguese, brought together essays by various experts, colour photographs and a detailed bibliography on Makonde sculpture. ↩

-

The bust of Ngungunhane, unveiled in Mandlakazi in 1995, was vandalised by some local residents days after its inauguration, reflecting the different interpretations of his figure: a national hero to some, an oppressive figure to others. ↩

-

Ualalapi (Maputo: Associação dos Escritores Moçambicanos, 1987) problematises the myth of Emperor Gungunhana from the perspective of political violence and colonial legacy; The Bones of Gungunhana (Maputo: Ndjira, 2011) addresses the historical memory of the emperor's exile; and The Emperor's Sands (Lisbon: Caminho, 2015-2017) revisits the fall of Gungunhana, blending fiction and history in the renewal of African collective memory. ↩

-

Photograph of the procession marking the return of Ngungunhane's remains to Maputo (15 June 1985), by Carlos Calado. Courtesy of the Arquivo Histórico de Moçambique. Source: Jornal Domingo, Maputo, 16 June 1985. ↩

-

Information obtained from the CNN Portugal podcast “Gungunhana: grave 404 and the search for remains” (2024) confirms that Gungunhana was buried in grave no. 404 in the Conceição cemetery (Angra do Heroísmo), but his remains are irretrievable due to the periodic renovation of shallow graves in the Azores. ↩

-

The Military Museum in Bragança, in northern Portugal, still has an exhibition of the military conquest in the 1895/96 campaigns, displaying objects alluding to Gungunhana (Portuguese spelling), such as "his trousers", without any critical recognition of the episode or attempt to put the historical events into perspective. ↩

-

At the time of the 2019 debate—where she delivered the final assessments—Muocha was working as a technician and researcher in the cultural sector. Only in February 2025 was she appointed Secretary of State for Arts and Culture, thereby assuming ministerial-level government responsibilities. ↩

-

See: AIM News, "Mozambique demands return of looted artefacts", 25 May 2025, https://aimnews.org; Club of Mozambique, "Mozambique demands return of artefacts looted during colonialism", 29 July 2025, https://clubofmozambique.com. ↩

-

See: Club of Mozambique, “Mozambique: Chissano advocates ‘good cooperation’ and investment, not reparations for colonial past,” 2025, https://clubofmozambique.com. ↩

BibliographieBibliography +

Books and Book Chapters

Chiziane, Paulina. (2015). Ngoma Eto. Maputo: Ndjira.

Chiziane, Paulina. (2017). O canto dos escravos. Maputo: Ndjira.

Couto, Mia. (2015-2017). As areias do Imperador. Lisbon: Caminho.

Cruz, Maria das Dores (2007). Portugal gigante: motherland and colonial encounters in Portuguese school textbooks. Habitus, 5(2), 395–422.

Cruz, Maria das Dores (2014). “The nature of culture: Sites, ancestors and trees in the archaeology of southern Mozambique”. In N. Ferris, R. Harrison & M. Wilcox (Eds.), The Archaeology of the Colonised and its Contributions to Global Archaeological Theory (pp. 123–149). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cruz, Maria das Dores (2022). Fractured landscapes and the politics of space: Remembrance and memory in Nwadjahane (Southern Mozambique). Museum Anthropology, 45(1), 57–71.

Guibunda, Gabriel. et al. (n.d.). O meu caderno de actividades de História – 12ª Classe. Maputo: Plural Editores / Ministério da Educação do Mozambique.

Ungulani Ba Ka Khosa (1987). Ualalapi. Maputo: Associação dos Escritores Moçambicanos.

Lichuge, Eduardo (2016). History, Memory and Coloniality: Analysis and critical reinterpretation of historical and archival sources on music in Mozambique (Doctoral dissertation). University of Aveiro.

Lichuge, Eduardo (2020). The timbila of Mozambique in the concert of nations. Locus Revue d’Histoire, 26(2), 261–290.

Miguel, Aaa. Elisa (2021). Community courts as mechanisms for promoting legal pluralism and strengthening informal justice in Mozambique. In Speaking the law: the role of courts in the 21st century.

Panguana, Marcelo (2011). Os ossos de Ngungunhane. Maputo: Ndjira.

Paulouro das Neves, José César & Oliveira, Paulo Alexandre (Eds.). (2021). Na primeira pessoa. Lisbon: Tinta-da-China.

Savoy, Bénédicte & Sarr, Felwine (2018). Rapport sur la restitution du patrimoine culturel africain: vers une nouvelle éthique relationnelle, https://bj.ambafrance.org/Telecharger-l-integralite-du-Rapport-Sarr-Savoy-sur-la-restitution-du

Vacha, Andrea., & Vene, M. (2024). Memoriais como recursos didáticos para o ensino de história da resistência anti-colonial em Moçambique: Análise dos monumentos Acivaanjila e Ngungunhane. Capoeira Revue des Humanités et des Lettres, 1(1).

Wane, Marílio. (2018). Timbila Tathu: Política cultural e construção da identidade em Moçambique. Maputo: Khuzula.

Journal Articles and News Reports

Bens culturais saqueados durante o colonialismo—África para África. (2019, February 21). Notícias.

Chissano defende 'boa cooperação' e não reparações. (2025, June 9). Diário Económico.

Moçambique ainda não tomou posição. (2019, January 17). Notícias.

Moçambique: debate sobre políticas de memória pós-colonial. (2025, September 8). Observador.

O retorno de Ngungunhane. (1985, June 16). Jornal Domingo.

Processo de devolução é irreversível. Portugal deve preparar-se & é imperativo devolver a nossa humanidade. (2019, March 13). Notícias.

Reparações históricas em África não se limitam a compensações económicas. (2025, June 8). Expresso das Ilhas.

Moçambique: Chissano advocates “good cooperation” and investment, not reparations for colonial past. (2025, June 9). Club of Mozambique.

Mozambique demands return of artefacts looted during colonialism. (2025, July 29). Club of Mozambique.