Introduction

I am writing from a personal point of view firmly rooted in my identity as an Indigenous woman from the Southwest trained in archaeology and museums. As a child, my parents taught me who I was as a member of their family and as a member of a wider community. As a student, my teachers taught me anthropological theory, museum practices, and professionalism. It is the memory of my lived and taught history that paints my identity today. This is the same for every individual who builds societal memory and thus cultural identity (Lowenthal 1985a, 197).

I propose we incorporate knowledge from psychology and indigenous groups to support fundamental changes in how conservation approaches cultural heritage preservation. First, drawing on psychology and the body of work in defining and treating Hoarding Disorder. Experiences of collection museums as institutions and the individuals working in them match those addressed in the clinical study of Hoarding Disorder. Furthermore, the treatment of Hoarding Disorder is frequently linked to an underlying trauma (Booker 2014; Halley 2019; Hombali et al. 2019). Seeing how Hoarding Disorder and its effect on memory is treated can provide insights into the museum’s relationship to tangible and intangible heritage. Secondly, I shall explore traditional knowledge systems as examples of memory building. My life experience in Indigenous America has shown me the resilience of community memory and how it can create active cultural preservation through interactions with collections. Knowledge systems such as these can provide examples of collective tools to overcome institutional hoarding.

Museums as Agents

In early accounts of notable collections such as the Library of Alexandria, the institutions are often referred to as the first museums. The precursor to the contemporary museum is recognized to be the cabinet of curiosity, dedicated to the presentation of special and unique objects to the curious. Collections moved from private, royal and church domains to public trusts and, by doing so, established the concept of the 20th Century Museum (Abt 2006). Recent changes in society have forced museums to adapt to social challenges, albeit slowly. In 2020, the International Council on Museums updated their 50-year-old definition of a museum.

A museum is a not-for-profit, permanent institution in the service of society that researches, collects, conserves, interprets and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage. Open to the public, accessible and inclusive, museums foster diversity and sustainability. They operate and communicate ethically, professionally and with the participation of communities, offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection, and knowledge sharing. (ICOM 2022)

This definition changes the status of museums from stagnant institutions to an active societal actor. As an entity that influences social identity coupled with its history as a container of artifacts, museums are now confronting many issues with their collections. In my experience, these issues are generally rooted in the ethical acquisition, storage, preservation/restoration, and deaccession of museum pieces. The Heritage Health Index of 2005 (Heritage Preservation 2005) points to storage and preservation/restoration as a major issue within American Museums generally. The survey indicated 30% of American collections were in an undocumented state of care. Of the documented collections, up to 54% of collections needed improvement for preservation, a statistic that has likely marginally changed in 15 years considering poor funding and resources for heritage preservation.

Recent news headlines about generational differences have highlighted a shift away from material possessions (Poplin 2021; Koncius 2015; Kouremetis 2021) which may result in an influx of material donations to museums (Stevenson 2017). The increase in requests to donate collections can be felt by many museum professionals. As more collections are added to museums the capacity for heritage preservation will continue to be inundated, forcing those who conserve these materials to face difficult questions of societal value and sustainability.

Preserving Memory by Collecting

What causes humans to collect is unclear and often unique to individuals and groups. There is a deep psychological component that is understood by an individual when explaining their collection choices. The things I collect provide memories of my experiences and thus my identity, from my first Kachina doll to my growing collection of Indigenous earrings. Materials provide a way to remember, connect with, or even forget the past (Lowenthal 1985b; Barreiro and Endsleff 2020; Munoz-Vinas 2023).

Personal photograph of a selection of my desk books and knick-knacks that reinforce my experiences and identity. (2024)

In the Museum

Early museums existed as physical places to hold materials collected by humans. In this context, collection institutions were places of prestige and power. The first collectors brought materials from distant places or purchased art to display their wealth and in some cases to save these artifacts of the past and present for the future (Abt 2006; American Association of Museums et al. 2010). Thus, the field of art and cultural heritage preservation and conservation became intertwined with collections and the museum.

The conservation field was born in an age dedicated to restoration. Restoration and repair are common human activities (Spelman 2002), but in Europe and the United States collaboration between restorers, scientists, and art historians led to a distinct field of art conservation (Stoner 2005). Eventually, the field was driven by the need to preserve materials as bearers of historical truth (Caple 2000). The undercurrents of this philosophy can still be felt in American museums which have large collections of things zealously stored and maintained for an unknown future. Museum exhibitions bring out the best-preserved materials, promoted by conservators who advocate material integrity under the current American Institute of Conservation’s Code of Ethics (American Institute for Conservation 1994).

As an intern with the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), I witnessed an exchange with collection managers, curators, and conservators around a boarding school uniform. Textiles are highly susceptible to deterioration due to light exposure. With the exhibition being extended, an exchange was proposed for another uniform from the collection. The conservator insisted the uniform on display remain as “the other uniform is in poor condition.” I was struck by this comment thinking that one uniform was being sacrificed for the other. The damaged uniform may have a story of its own but was denied the opportunity to present it because of material concerns for the item. Still, the museum maintained this uniform in storage even though the use is limited by its fragility. In 2024, it was decided to perform conservation treatments of this uniform for display. The conservator uncovered a rich history surrounding the man who owned this uniform and gave it a chance to tell its story now on display at NMAI.

Uniform worn by Buffalo Child Long Lance during his years at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School (1909-1913). On display in “Nation to Nation” at the National Museum of the American Indian. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (18/939)

Today, values guiding preservation practices are contested as museum staff face economic challenges and societal demand for access and transparency. These difficulties are issues that present parallels with Hoarding Disorder.

Hoarding Disorder

Hoarding is a word rooted in old English which means “a treasure, valuable stock or store, an accumulation of something for preservation or future use.” (“Hoard” 2023) Collecting or accumulation is seen as a normal human experience. In some cases, collection is deemed problematic when an individual or a group amasses materials to the point of hurting their physical wellbeing. Historical evidence of such disordered behavior is hard to pinpoint without written documentation but is assumed to have occurred since the beginning of human collecting (Penzel 2014).

In the field of psychology, this disorder was considered a manifestation of obsessive-compulsive disorder, linked to a compulsion to acquire and preserve materials. It wasn’t until the 1990s that Hoarding Disorder became a separately recognized psychological disorder defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (2013, 292). Clinical Hoarding Disorder is characterized by a dysfunctional relationship to items with a primary focus on the difficulty in discarding items. This is separate from the related propensity to acquire items by accumulation, purchasing, passive or active collecting. This clinical separation of diagnosis allows a deeper exploration of its possible origins and treatment.

Studies of Hoarding Disorder report a high frequency of onset resulting from a traumatic or stressful event. Events reported by those who hoard include a change or loss in a relationship, past violence including sexual assault, and/or past loss or damage to items. These life events are more prevalent in hoarding onset later in life. Hoarding is often a complex disorder frequently happening in conjunction with other mental disorders such as OCD, depression, and generalized anxiety with similar compounding origins in biology and emotional stressors. (Steketee and Frost 2014; Kyrios 2014)

Hoarding Disorder is estimated to be present in 2.3% to 6% of the population (Steketee and Frost 2014, 25). These statistics are difficult to define in a clinical space requiring individuals to participate in surveys and self-awareness of disordered behavior – the lack of self-awareness is a specifier of the disorder (Table 1). Many undocumented cases of hoarding have not reached a situation requiring intervention and treatment meaning this disorder could be more prevalent than statistically proven.

Museum Hoarding

In 2017, Dr. Gail Steketee, a clinical psychology researcher focusing on Hoarding Disorder and OCD, provided a comprehensive appraisal of the possible overlaps of Hoarding Disorder in museum spaces (2018a). She addressed the relationship of clinical Hoarding Disorder to the museum collection as an institution and individuals working in museums.

Applying the criteria of distress and impairment for individual hoarding to museums is not a perfect fit but is an interesting exercise. Just as impairment in living space and daily functioning constitute criteria for Hoarding Disorder, acquisitions and organization that pose a burden on the museum staff, its budget, or the available space might be considered excessive. For example, when museum storage areas begin to resemble a hoarded home with disorganized piles cluttering the space so it is difficult to know where any given object is located and what it means (Steketee 2018a, 56).

Steketee is rooted in clinical psychology where the focus is on the individual. I believe that we can build on Steketee’s work and draw further parallels to groups and institutions that will allow the field of cultural heritage preservation to draw from psychology literature. The history of museums and collection history, particularly in the United States, has been recognized as tumultuous. Many collections are built on acquisitions obtained unethically by today’s standards; materials were taken out of context and boxed up in the name of preservation. Today, this is viewed as disruptive to both the originating community and the ethics of the collection itself. This disruption can be defined as trauma (Brown 2004; Walsh and Kokoli 2022; Smithsonian Institution 2022).

Collections’ trauma has been addressed in the interpretation and exhibition of cultural heritage in museums. I propose we instead examine collections and conservation as spaces of trauma. Museum collections struggle to ethically address the decaying, redundant, unprovenanced, or unvalued collections sitting in their storage. Conservation history is checkered by the struggles surrounding the uniqueness of each object and the need to preserve for the future while controlling material objects (American Institute for Conservation 1994; Caple 2000; Clavir 1998). The incorporation of Hoarding Disorder into the ethical discourse of the conservation field can have an impact on many concerns voiced by working conservators in approaching the inevitable decay of materials and their contemporary cultural use.

Treatment of Hoarding Disorder

The treatment of Hoarding Disorder in individuals typically involves a cocktail of therapies and medication (Muroff 2014; Beck 1979; Steketee 2014; Saxena 2014). The two methods together are proven to be effective when applied consistently over an extended time. Medications are an individual application of treatment and are not applicable to this discussion. However, treatment including group therapies is effective in addressing personal histories and traumas. This is a tool that can be drawn upon to find ways to instill positive changes in cultural heritage preservation.

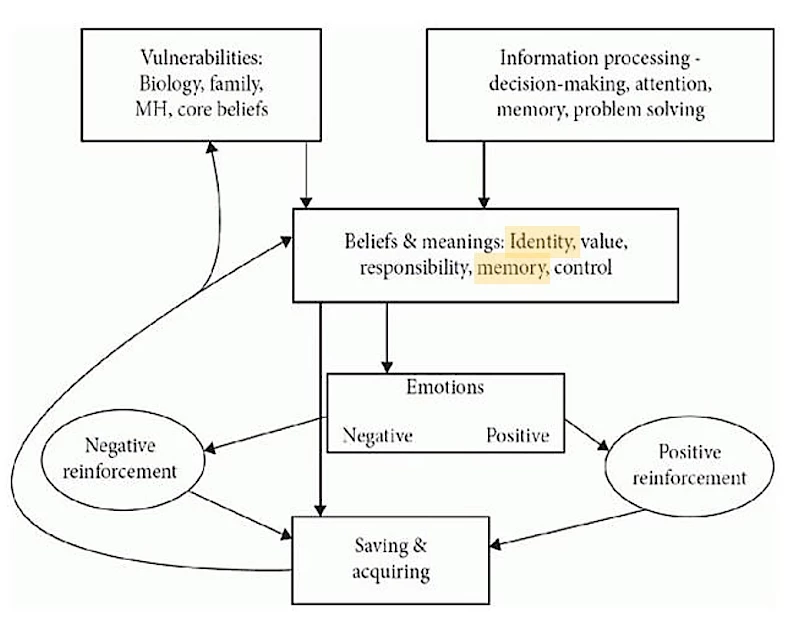

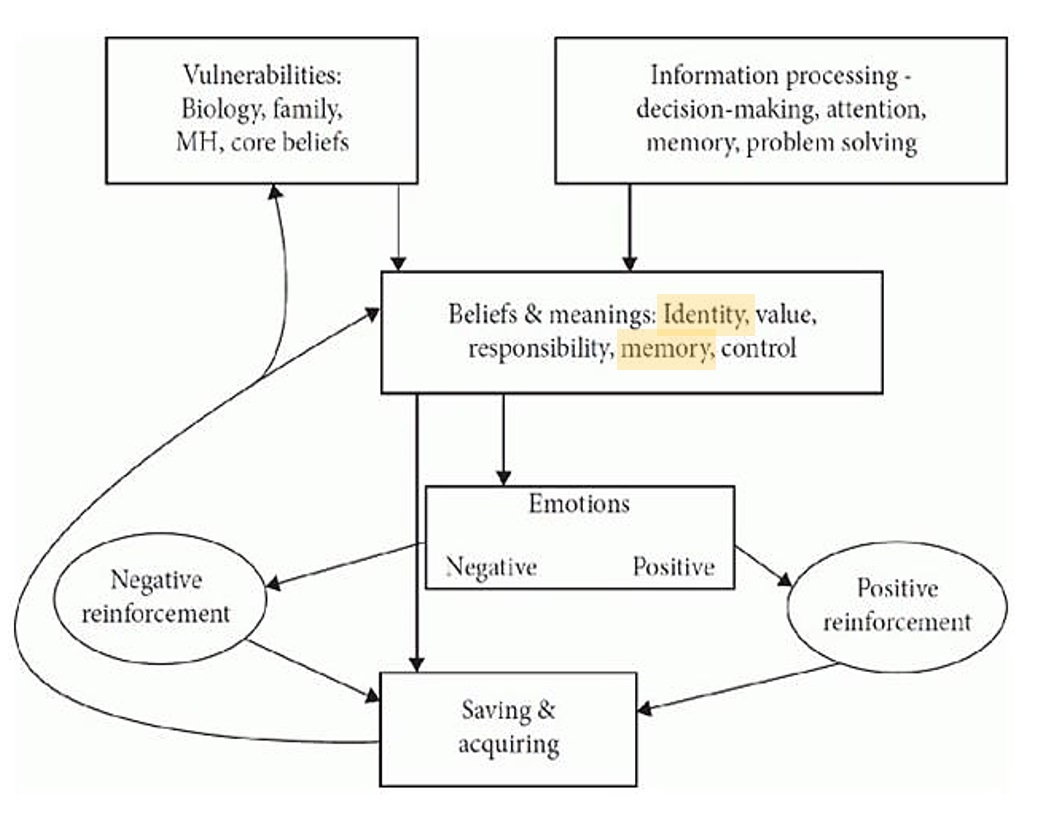

A widely used therapy is cognitive-behavior therapy. Behavior is defined as the process by which a thought and its resulting feelings lead to action (Beck 1979). In therapy, a patient and therapist target mental distortions and regulation cycles to disrupt thoughts and change behavior. A cognitive-behavioral cycle of Hoarding Disorder has been described in Figure 1 (Steketee 2014, 262). This cycle is centered around concepts of identity that fuel emotional responses. Therapy targets those emotional responses to change internal assumptions and beliefs. This approach can be used in a community setting allowing a group of individuals to change individual behavior (Malone, McCormack, and McCullough 2022; Bratiotis and Woody 2014). Understanding this behavior model can give museum and conservation professionals a framework to address an institutional level of hoarding behavior.

Hoarding Disorder cognitive and behavior model developed by Dr. Staketee. Identity and memory highlighted by the author to show their central location to the cognitive-behavior cycle. ©Oxford University Press

Dr. Gail Steketee outlined “common hoarding belief ‘traps’ or emotional responses that may be relevant to the management of museum collections”(2018b, 121) such as potential usefulness, fear of making mistakes, responsibility and guilt, emotional attachment and loss, control, and overthinking. Many of these “traps” are discussed in the philosophy and ethics of conservation work as established in colonial states (Stoner 2005; Clavir 1998). Part of cognitive-behavior therapy is challenging the validity of belief traps with questions and behavior experiments. Questions are asked to confront the reality of use, preservation, quality, value, and need of the material. Behavior experiments test the effect of placing an item out of perception and revisiting it after a length of time to see if the loss of the item was impactful. These may be useful steps to work within the existing museum framework and are particularly useful when looking towards ways to incorporate alternative knowledge systems to changing our relationship with materials as has been seen in small changes at institutions with Indigenous collections (Carrlee, Tjiong, and Gendron 2023; Haakanson 2022; Evans 2022).

Personal Reflections from an Indigenous Perspective

Indigenous communities inhabit all areas of the world and hold with them a wide breadth of diversity filled with traditional knowledge adapted to their lands and cultural identity. Presented here are some points of interest from Indigenous communities and their histories that relate to concepts of cultural memory and identity and thus community behaviors towards material as examples of regulating disordered hoarding practices.

A central historical point in Indigenous North America is colonization and its lasting effects. This is acknowledged as a point of trauma for communities that resulted in significant loss of populations, land, and cultural memory. Colonization has been a continual process seen over centuries from the landing of Columbus to governmental injustices and attacks on tribal sovereignty in contemporary law. This has resulted in an extensive study of historical traumas and the impact of historical events on survivors and their descendants (Kirmayer, Gone, and Moses 2014; Brave Heart and DeBruyn 1998; Brown-Rice 2013). Having grown up and worked in and around indigenous people I have noticed the employment of ideologies that support community identity and memory and thus a regulated response to the life cycle of cultural material.

From a Pueblo Perspective

I am writing from my lived experience as a member of the Hopi Tribe living and working in Pueblo Cultures found in the American Southwest. My statements are formed through interactions with a wide variety of Pueblo people but are not representative of the diversity found across the Pueblo communities. There are 21 federally recognized tribes recognized as Puebloan. Each community has unique traditions, yet after many generations of exchange and adaptation to the arid mountain desert, there is shared history and cultural familiarity. It is this familiarity and shared history that I educated the public about for five years at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center. Pueblo identity has been maintained through cultural memory passed down orally over many generations and survived under many threats. Core Pueblo ideologies like life cycles and cultural continuation are centered in a sense of community maintained since time immemorial. It is these tenants and the way of passing them down that magnify cultural identity and shape relationships between individuals (Bird 2018) and cultural heritage materials.

When our ancestors were formed in the earth, they were given the breath of life. After traveling through the underworlds, they emerged into this world; they were given instructions on how to live in this world. The original instructions included traditions such as how to dance, how to plant, and how to treat other living beings. Integral to each of these instructions was the nature of cycles. As the seasons changed in consistent cycles, so did the plants we subsisted on growing seed to germinate, in order to harvest, to allow the soil to rest before going back to seeding. This concept is a pattern applied to all living things. We each will experience a cycle of life: breath of life, youth, elderhood, and death. Anything made by our people was also given a breath of life by the creator and thus a life cycle. It is not the material itself that is imbued with value, but the spirit housed within it. Recognizing a material life cycle, the value of cultural material is in the intangible elements such as the knowledge of how to make it and how to use it. In practice, this means that materials will reach a point where they are allowed to naturally decay and return to the elements such as adobe homes (Swentzell 1976), broken ceramics, and ceremonial masks. This is not viewed as a loss because it allows for the next cycle to continue, and knowledge is taught to the next generation.

Continuation is a value embodied by our people. We are among the few Indigenous groups in America that inhabit a portion of our original ancestral lands. Despite many threats to our existence, pueblo ways of life have persisted. In the 1600-1700s European missionaries condemned traditional knowledge and practices. They imposed brute force to eradicate non-Christian beliefs and practices. In the 1950s the American government instituted the Indian Relocation and Termination Policy. This included acts that forcibly removed Indigenous peoples from their lands and their families in an attempt to erase them (Fixico 1986). This and other historical traumas pushed Pueblo culture into secrecy, which can be felt today. Traditional knowledge is hoarded for fear of destruction or abuse from outsiders. Many Puebloans lost traditions over the course of history which are being revitalized today as memories are reunited with cultural material. It is when intangible culture is joined with the tangible that the continuation and life cycle of cultural traditions and community identities is fostered.

Conclusion

The field of cultural heritage preservation has experienced a shift in its approach. Conservation as a field was born from the field of restoration and the desire to preserve tangible heritage. This desire has culminated in museums across the world with large storage areas filled with heritage items collected for their perceived value for a future time. As these collections have grown, the capacity to care for them is exceeded as seen in the Heritage Health Index. The inevitable inability to care for, de-access, or permit the use of cultural heritage items is an issue deeply rooted in the framework of cultural heritage preservation. Recent strides in the field of conservation hint at the desire to shift away from hoarding of material and focus on social and cultural needs (Foundation for Advancement in Conservation 2023; Miller and Poh 2022).

I am honored to be among a cohort of emerging professionals focused on social justice, diversity, equity, and sustainability in conservation. We are seeing greater inclusion of diverse communities in the decision-making of conservation. Conservators are supporting repatriations, community led research, and the culturally sensitive care of cultural heritage as a field uniquely placed between sciences and humanities. Conservation as a collaborative and inclusive practice is equipped to approach cultural heritage with an eye to the mechanisms of memory and identity built through the tangible and intangible.

Here I considered the parallels between collections staff, the museum collection, and Hoarding Disorder. While the comparisons are not perfect, we can still use approaches from the treatment and understanding of Hoarding Disorder to find new ways to manage tangible heritage – namely ways to accept the loss of materials while maintaining memory and identity. The relationship between Indigenous communities, tribal identity, and tangible heritage is a model of a balanced relationship with materials. Despite the traumas experienced by Indigenous people, their reliance on generational community knowledge to guide their identity through cycles of material existence is having an impact on staff working with Indigenous collections. Hordes of Indigenous collections do not hold cultural memory; it is the people that hold the memory. When the people and materials become connected, the lives of both the people and objects are fulfilled and cultural memory is renewed.Mazen Iwaisi’s traditional family house. These events and workshops will provide opportunities for residents to actively participate in the curation process. In addition, we are considering collaborating with local schools to develop educational programs that engage students in learning about the history and culture represented in the museums. Furthermore, creating volunteer opportunities for community members to contribute their skills and knowledge would foster a sense of ownership and pride in preserving their heritage.

BibliographieBibliography +

Abt, Jeffrey, “The Origins of the Public Museum”, in Sharon Macdonald, A Companion to Museum Studies, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2006, 115–34.

Buck, Rebecca and Jean Gilmore, MRM5: Museum Registration Methods 5th edition, Washington, DC, AAM Press, American Association of Museums, 2010

American Institute for Conservation, “Code of Ethics and Guidelines for Practice”, 1994.

American Psychiatric Association and American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Task Force, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed., Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Barreiro, Alicia and Inga Endsleff, “Remembering and Forgetting: A Crossroad Between Personal and Collective Experience”, in Maria Lyra, Brady Wagoner, and Alicia Barreiro Imagining the Past, Constructing the Future, Springer International Publishing, 2020, 71–87.

Beck, Aaron, Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders, East Rutherford, Penguin Publishing Group, 1979.

Bird, Peggy, Pueblo Women’s Knowledge: Voices of Resilience and Transformation in the Face of Colonization, Arizona State University, 2018.

Booker, Bobbi, “Expert Explains ‘grief, and Tragedy’ Cause Hoarding.” Philadelphia Tribune, 130(95), 2014.

Bratiotis, Christiana, and Sheila Woody “Community Interventions for Hoarding”, in Randy Frost and Gail Steketee, The Oxford Handbook of Hoarding and Acquiring, Oxford University Press, 2014, 316-28.

Brave Heart, M. and L. DeBruyn, “The American Indian Holocaust: Healing Historical Unresolved Grief”, American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: Journal of the National Center 8 (2), 1998, 56–78.

Brown, Timothy “Trauma, Museums and the Future of Pedagogy”, Third Text 18 (4), 2004, 247–59.

Brown-Rice, Kathleen “Examining the Theory of Historical Trauma Among Native Americans”, The Professional Counselor 3 (3), 2013, 117–30.

Caple, Chris “Reasons for Preserving the Past”, in Conservation Skills, New York, Routledge, 2000, 26-42.

Carrlee, Ellen, Amy Tjiong, and Adrienne Gendron “Reflections on Authority in the Conservation of Indigenous Cultural Heritage in Museums”, in Nina Owczarek, Prioritizing People in Ethical Decision-Making and Caring for Cultural Heritage Collections, London, Routledge, 2023.

Clavir, Miriam, “The Social and Historic Construction of Professional Values in Conservation”, in Studies in Conservation, 43 (1), 1998, 1–8.

Evans, Rose, “Hoki Mauri: Bring Back the Life Essence”, in Peter Miller and Soon Kai Poh, Conserving Active Matter, Bard Graduate Center, 2022, 283–300.

Fixico, Donald, Termination and Relocation. Federal Indian Policy, 1945-1960. University of New Mexico Press, 1986.

Foundation for Advancement in Conservation. 2023. “Held in Trust: Transforming Cultural Heritage Conservation for a More Resilient Future”, 2023, https://www.culturalheritage.org/docs/default-source/publications/reports/held-in-trust/held-in-trust-report.pdf.

Haakanson, Sven, “Living Knowledge in Cultural Collections”, in Peter Miller and Soon Kai Poh, Conserving Active Matter, Bard Graduate Center, 2022, 234-45.

Halley, Catherine “What’s Causing the Rise of Hoarding Disorder?”, JSTOR Daily, January 16, 2019.

Heritage Preservation. “A Public Trust at Risk: The Heritage Health Index Report on the State of America’s Collections”, Heritage Health Index, Heritage Preservation, Inc., 2005.

“Hoard”, Etymonline, 2023, https://www.etymonline.com/word/hoard.

Hombali, Aditi, Vathsala Sagayadevan, Weng Mooi Tan, Rebecca Chong, Hon Weng Yip, Janhavi Vaingankar, Siow Ann Chong, and Mythily Subramaniam, “A Narrative Synthesis of Possible Causes and Risk Factors of Hoarding Behaviors”, Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 42 (April), 2019, 104–14.

ICOM, “ICOM Approves a New Museum Definition”, International Council of Museums, 2022, https://icom.museum/en/news/icom-approves-a-new-museum-definition/.

Kirmayer, Laurence, Joseph Gone, and Joshua Moses, “Rethinking Historical Trauma”, Transcultural Psychiatry 51 (3), 2014, 299–319.

Koncius, Jura, “Stuff It: Millennials Nix Their Parents’ Treasures”, The Washington Post, March 27, 2015.

Kouremetis, Dena “Why Many Adult Children Just Don’t Want Their Parents’ Stuff”, Psychology Today, January 5, 2021.

Kyrios, Michael, “Psychological Models of Hoarding”, in Randy Frost and Gail Steketee, The Oxford Handbook of Hoarding and Acquiring, Oxford University Press, 2014, 206–20.

Lowenthal, David, “Preservation”, in The Past Is a Foreign Country, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1985a, 384–406.

———, The Past Is a Foreign Country. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1985b.

Malone, Aoife, David McCormack, and Emma McCullough, “A Remote Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Approach to Treating Hoarding Disorder in an Older Adult”, The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 15: e21, 2022.

Miller, Peter and Soon Kai Poh, Conserving Active Matter. Bard Graduate Center, 2022.

Munoz-Vinas, Salvador, A Theory of Cultural Heritage: Beyond The Intangible. 1st ed. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2023.

Muroff, Jordana, “Alternative Treatment Modalities”, in Randy Frost and Gail Steketee, The Oxford Handbook of Hoarding and Acquiring, Oxford University Press, 2014, 274–90.

Penzel, Fred, “Hoarding in History”, in Randy Frost and Gail Steketee, The Oxford Handbook of Hoarding and Acquiring, Oxford University Press, 2014, 6–16.

Poplin, Julianna, “Sorry Parents, Millennials Don’t Want Your Stuff”, The Simplicity Habit (blog). May 7, 2021. https://www.thesimplicityhabit.com/millennials-dont-want-your-stuff/.

Saxena, Sanjaya, “Pharmacotherapy of Compulsive Hoarding”, in Randy Frost and Gail Steketee, The Oxford Handbook of Hoarding and Acquiring, Oxford University Press, 2014, 291–302.

Smithsonian Institution, “Smithsonian Adopts Policy on Ethical Returns”, Smithsonian Institution News. May 3, 2022.

Spelman, Elizabeth, Repair: The Impulse to Restore in a Fragile World, Boston, Beacon Press, 2002.

Steketee, Gail, “Individual Cognitive and Behavioral Treatment for Hoarding”, in Randy Frost and Gail Steketee, The Oxford Handbook of Hoarding and Acquiring, Oxford University Press, 2014, 260–73.

———, “Hoarding and Museum Collections: Conceptual Similarities and Differences”, in Elizabeth Wood, Rainey Tisdale, Trevor Jones, Active Collections, 1st ed., Routledge, 2018a, 49–61.

———, “Practical Strategies for Addressing Hoarding in Collections”, in Elizabeth Wood, Rainey Tisdale, Trevor Jones, Active Collections, 1st ed., Routledge, 2018b, 120–26.

Steketee, Gail and Randy Frost, “Phenomenology of Hoarding”, in Randy Frost and Gail Steketee, The Oxford Handbook of Hoarding and Acquiring, Oxford University Press, 2014, 18–32.

Stevenson, Jen, “Have Collections Your Kids Don’t Want? Museums Might Be the Answer”, The Post-Crescent, September 16, 2017.

Stoner, Joyce, “Changing Approaches in Art Conservation: 1925 to the Present”, in Scientific Examination of Art: Modern Techniques in Conservation and Analysis, Washington, D.C., The National Academies Press, 2005, 40–57.

Swentzell, Rina. An Architectural History of Santa Clara Pueblo. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 1976.

Walsh, M and A Kokoli, “Trauma and Repair in the Museum: An Introduction”, Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, 27, 2022, 4–19.