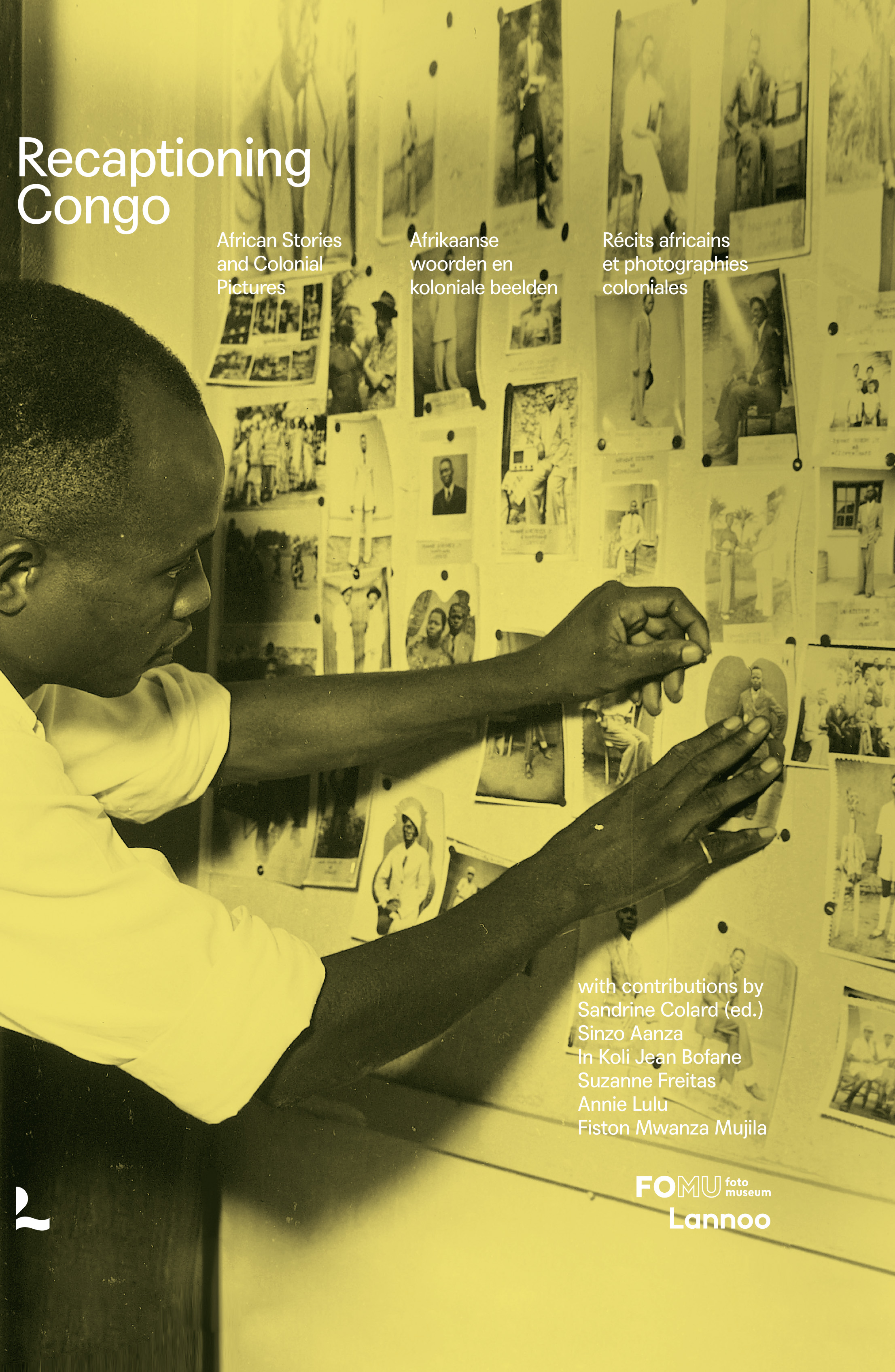

Joint review of the exhibition Recaptioning Congo, curated by Sandrine Colard at FOMU Antwerp (16 September 2022 – 15 January 2023), and the accompanying book Recaptioning Congo. African Stories and Colonial Pictures, Antwerp, FOMU Antwerp, Laanoo, 2022.

Can a photography exhibition correct or at least question the narration and perception of history? How can propaganda images be deconstructed? And what role does the juxtaposition of photographic material that contrasts the perspectives of the colonial rulers with those of the colonized play in this process?

The exhibition « Re-Captioning Congo, » curated by Brussels-based curator and scholar Sandrine Colard and on view at FOMU Antwerp from September 17, 2022 to January 15, 2023, addressed no lesser questions. The project built on the findings of her PhD research and took its starting point in the context of the 6th Lubumbashi Biennale 2019, which Colard conceived as artistic director. Together with curatorial assistant Maguy Watunia Mampasi, she invited Lubumbashi residents from different generations and backgrounds to comment on colonial photographs in order to share their own stories of the period shown on the images in the run-up to the Biennale. Combining colonial administration’s imagery with African photographers’ vernacular images, a series of diptychs revealed the “double-consciousness » that Black people have historically experienced in racist and colonized societies, divided between their own self-image and “the sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others » (Colard 2022, p. 15). Mounted on wooden panels, the photographs were presented with quotes from interviews that Maguy Watunia Mampasi held in June 20019 with the residents, referring to their memories, names and backgrounds.

Exhibition View. Recaptioning Congo, FOMU Antwerp, 16 September 2022 – 15 January 2023, © We document art/ FOMU Antwerp.

« Re-Captioning », in English stands for the “act of taking, reprisal”, especially “peaceful extralegal seizure of one’s own property wrongfully taken or withheld” (Colard 2022, p. 14). It plays with the double meaning of the word, in its use in the field of photography: adding new captions allows to tell new stories. The exhibition at FOMU Antwerp follows the dialogical approach of the 6th Lubumbashi Biennale and enacts a reappropriation or recapture of colonial photography, transposing it thus into a transformative memory culture capable of correcting dismissive representations in a manner that is as confrontational as it is empowering.

The five different exhibition sections developed a redefinition of visuality addressing the underlying power structures that are replicated and implemented in colonial image material that speaks back to King Leopold II and Belgium’s massive visual propaganda strategy during their cruel colonial rule in the Congo from 1885 to 1908, and 1908 to 1960 respectively, while supplementing it with a variety of African perspectives that are still inadequately represented in Europe today. Rather than relying on archival material from Belgian collections, the exhibition combined photographic material from the AfricaMuseum Tervuren and the collection of the Fotomuseum Antwerp, with amateur and studio photographs by photographers from the Congo. Following a broad approach to the visual representation of the Congo, and its evolution throughout the 20th century, colonial archives of the Belgian colonization in Central Africa, Union Coloniale Belge; contemporary photographs; images by the Centre d’information et de documentation/ Inforcongo; images from W.E.B. Dubois exhibition in 1900, and photographs by the Congolese photographer Jean Depara have been brought together.

The first two exhibition sections focused on the history of colonization around 1908, when Leopold II was forced to cede the Congo to the Belgian state after the horror of its merciless exploitation became public. Some photographs were taken by African-American missionary William Henry Sheppard (1865-1927), who documented the atrocities of the Belgians mining rubber in the Congo and was the first to speak of a « crime against humanity. » In a separate room marked with trigger warnings, unbearably brutal photographs and films of chopped-off hands and mutilated limbs, including many children, were shown. It displayed images by the Congo Reform Association that had been founded in the United Kingdom, to denounce the king’s regime and recurred for this purpose to an international photographic campaign. Although the reproduction of such explicit, traumatic imagery is controversial, in the context of the exhibition it is chosen deliberately in order to account for the historical impact of these representations. In the exhibition’s catalog, Sandrine Colard addresses a paragraph to “the responsible reader” to let them choose if they want to avoid being exposed to the visual representation of the “Congo atrocities ». She encourages those who do not know them to look with the “awareness that their position as consumers of violent images against Africans has been part of a global problem, one that has turned the suffering of Black people into a stereotype” (Colard 2022, p. 66). The third part of the show has been devoted to propaganda footage commissioned as a result of the « unfavorable reporting from Congo » in order to convince Belgians of the colonial project and to win them over for work on the ground. Congo is staged in these images as a place ‘of longing’ that is supposed to serve and resemble the Belgian way of living. The Congolese depicted in the photographs are thereby degraded to objects that resemble extras of an atrocity utopia marked by luxury and escapism. While being produced as justification for the so-called ‘civilizing mission’, the grossly cynical and overstaged visualization of the colonial ambitions can today just as well be read as exposure of the colonial mentality.

Exhibition View. Recaptioning Congo, FOMU Antwerp, 16 September 2022 – 15 January 2023, © We document art/ FOMU Antwerp.

Dedicated to the last 15 years of the colonization of Congo, the two last sections have been developed around the peak of Belgian propaganda and the international pressure advocating for independence. A photograph by Robert Lebeck shows Ambroise Boimbo, a former Congolese soldier, snatching King Baudoin’s ceremonial sword during his visit to Leopoldville in 1960, performing colonial power by driving standing in an open limousine through a crowd of people. The famous image focuses on the contestation of colonization by the Congolese people, and states that the control over the country is already no longer in Belgian hands. A new era is to come, that is also depicted in the last and fifths exhibition section focusing on Angolan photographer Jean Depara (1928-1997) who arrived in Léopoldville in 1951. His series of photographs provides insight into the scintillating African subculture of the Congolese capital in the 1950th and 1960th, depicting proud bodybuilders, couples in love at night, and elegantly dressed women at the bar. Capturing moments of unleashed freedom and multiplicity of stagings of Congolese urban life styles, the photographs anticipate the imminence of the country’s independence and thus celebrate “those who transgressed the colonial model of the middle-class Christian family” (Colard 2022, p. 174). Depara shows a proud and liberated image of Kinshasa’s citizens that differs from stereotypical colonial propaganda, as Sinzo Aanza states in the exhibition catalog: “Unlike in many photographs of that time, they do not parade in front of Depara’s lens merely to feel alive and vividly inscribe in the moment in the image that the photographer will have to produce. (…) while still others –suit-and-tie-types, bad boys, cool guys– are already eager to take on the responsibilities, posing with awareness and charisma required for the responsibilities that await them.” (Aanza, p. 177-78) By adding quotes from the interviews that Maguy Watunia Mampasi held as part of the 6th Lubumbashi Biennale, the photographs are contrasted with the ‘real’ life experience of the Congolese residents, referring to their very different memories and backgrounds. Ending the exhibition parcours with this proud and emancipated chapter of Congolese photography, the curatorial approach refuses to display and explain colonial image material through its own visual clichés. In the contrary, it juxtaposes the highly problematic archival material with a multiplicity of African photographers and voices who present their own intimate self-images through photographs and texts. By doing so, the exhibition challenges the norm that has become the (colonial) photographic representation of Congo as designed by sovereign power and focuses instead of shared life experience from the people behind the clichés. It thus could be interpreted as a vivid, confrontative, painful but also joyful way of working with problematic image archives, developing a striking “countervisuality” in the sense of Nicholas Mirzoeff: it doesn’t just offer a different way of seeing or looking at images but presents tactics to dismantle the visual strategies of colonial hegemonic systems that have established the Western domination of the word (Nicholas Mirzoeff: The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality. Duke University Press, 2011).

Book Cover. Sandrine Colard (ed): Recaptioning Congo. African Stories and Colonial Pictures, Antwerp, FOMU Antwerp, Laanoo, 2022.

The exhibition has been accompanied by a carefully conceived book, edited by Sandrine Colard under the title Recaptioning Congo. African Stories and Colonial Pictures, and published by FOMU Antwerp and Laanoo. Departing from a classical catalog, the volume extends the idea of recaptioning, inviting five writers of Congolese citizenship and descent to comment on the images in fictional or essay form. The approach of « recaptioning » is extended here through literary texts: the point is to counter the captions of colonial photography and its double meaning, both « a description accompanying a picture, photograph or illustration » and from Latin captionem, « a catching, seizing, holding, taking » with a « recaption », and thus the recovery of one’s property or story.

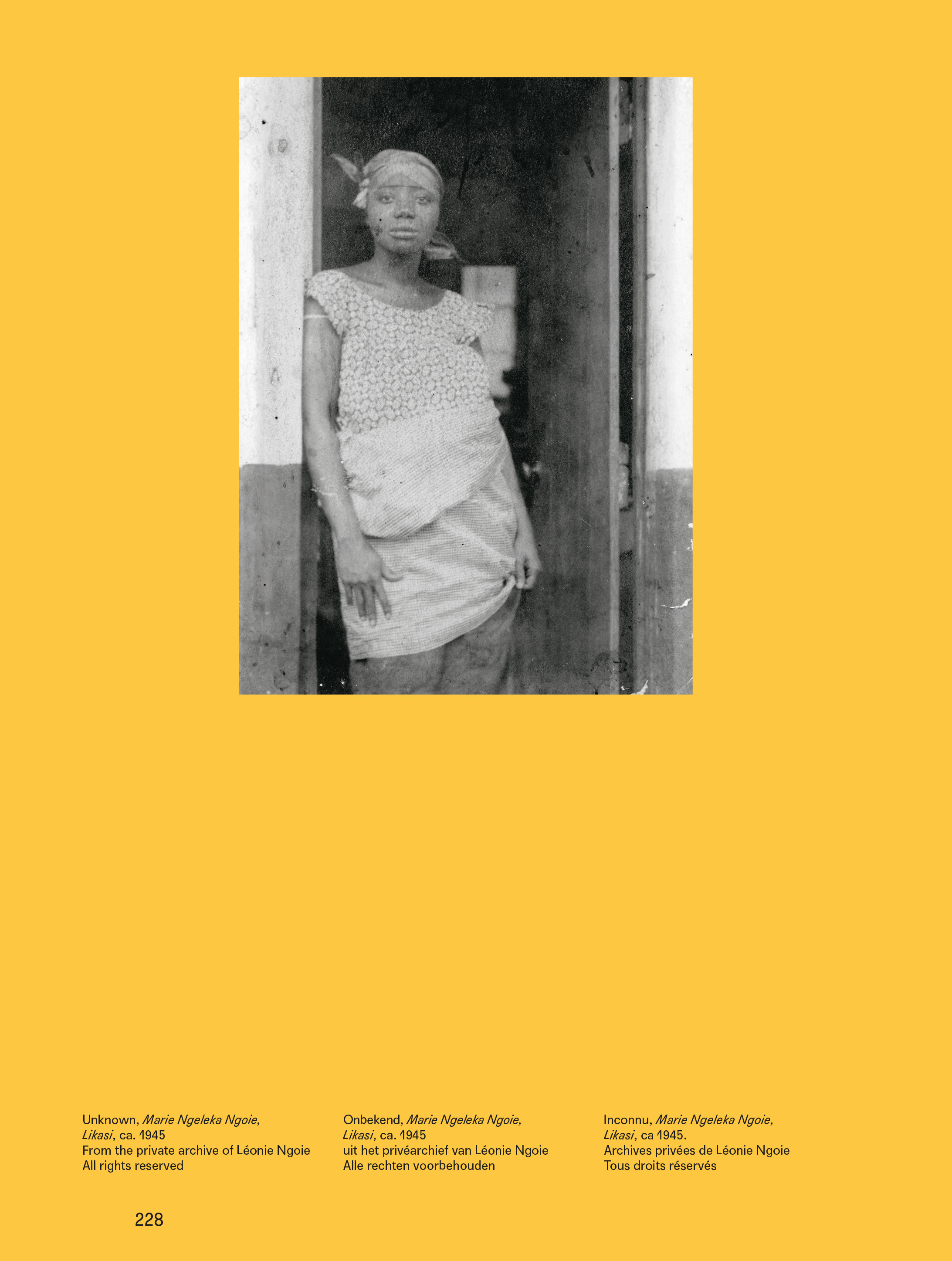

In this perspective, the six chapters of the trilingual volume (English, French, Flemish) contain both the contemporary short captions (crossing out racist descriptions) and longer literary essays that counter the dominance of the discourse on the photographic representation of the African continent by Western authors with the voices of Congolese writers. They are divided into six sections that follow a chronological structure, organized by La Villa Hermosa’s graphic design in full-page covers in bright colors alluding to the sociological graphics of African-American scholar and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois. Hereby, the book connects to Du Bois’ famous exhibition of portraits of African Americans during the 1900 Paris World’s Fair and the importance he placed on black photographic self-representation and the Pan-African project.

Furthermore, the chronologically chaptered photographic archives are accompanied by the texts of the writers Fiston Mwanza Mujila, Suzanne Freitas, In Koli Jean Bofane, Sinzo Aanza, and Annie Lulu. Following Sandrine Colard’s concept, this proceeding aims to propose « renewed and expanded captions for European and African images from the colonial period » while expanding the possible range of interpretation: « Rather than attaching definitive significations, as viewers of colonial photography in Africa have become accustomed to, [the authors] explore the multiple and unruly declinations of photographs interpretations to offer a compilation of reimagined or underrepresented stories. » (Colard 2022, p. 15).

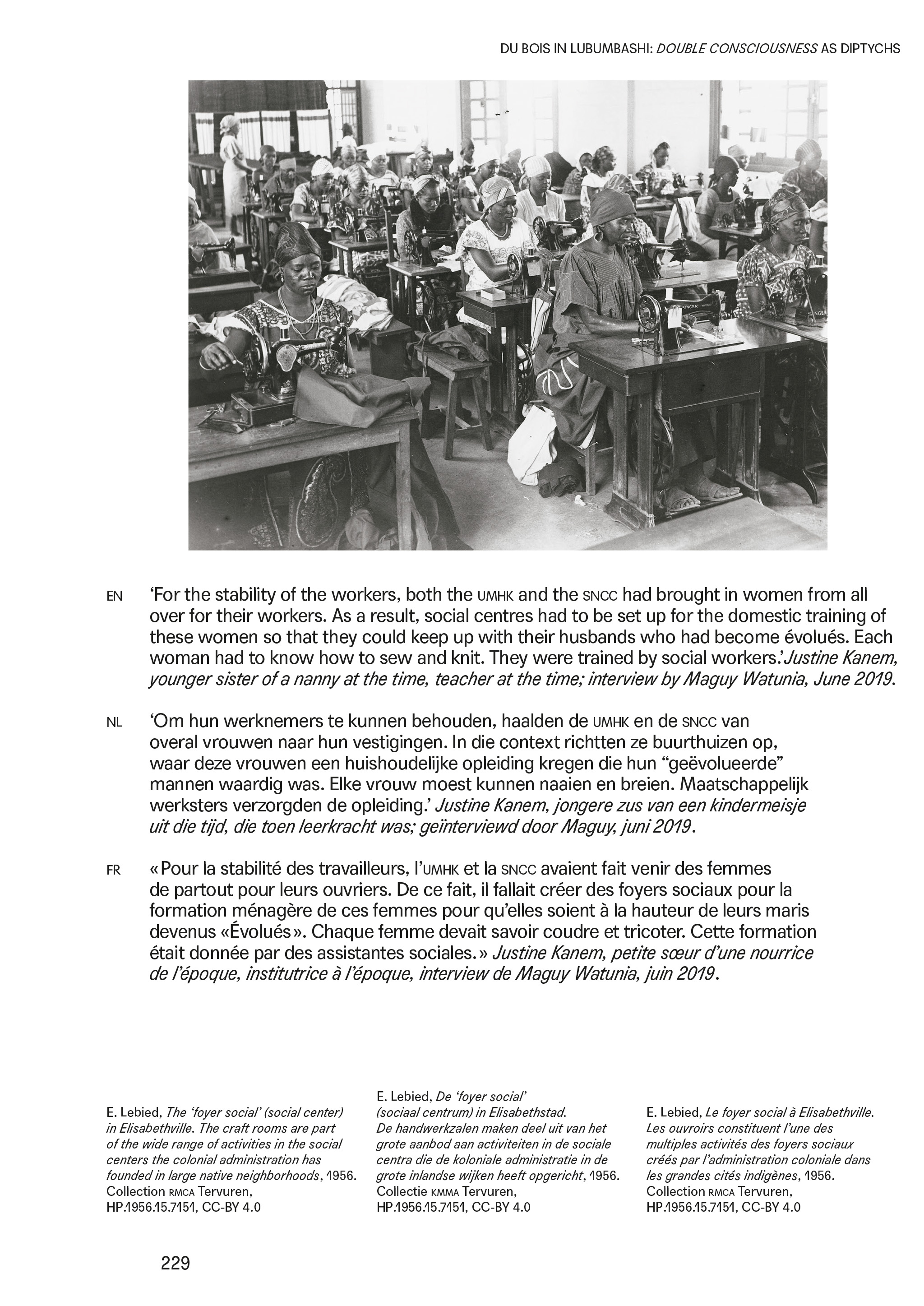

The approaches are varied: Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s eloquent « Kasala for myself » is juxtaposed with images of destruction during the Congo Free State period. Suzanne Freitas contributes a self-reflexive auto-biographical text on the practice of her father, Congolese-Angolan photographer Antoine Freitas (1902-1966), who ran a photography studio in colonial Leopoldville. Her text gives a vivid impression of the family’s life and Freitas’s work that goes far beyond a one-line biography. In Koli Jean Bofane writes in dialogue with images from the archives of the Center for Information and Documentation/Inforcongo that show the class of « évolué.e.s » that emerged in the interwar period. In sharp contrast to the colonial discourse on the desirability of such status, which depended heavily on recognition by the colonizers, Bofane’s strident dialogues reveal the people’s judgment of the hierarchies that colonial society imposed on them: « To be elegant, to speak French, to wear a tie, there’s no harm in that, that’s clear. But évolué, what is that? I’ll wait a little longer, we’ll soon have independence. » (Bofané, p. 143).

A choice with many trans-temporal echoes, Colard has invited the writer and artist Sinzo Aanza to contribute a text relating to the images of Jean Depara, who photographed in the nineteen forties the urban life in Leopoldville. Sinzo Aanza calls himself the poet of the city and dedicates many of his texts to the burgeoning life in the city of Kinshasa. The scintillating dialogue between Depara’s images that celebrate the beauty, creativity and spirit of city’s inhabitants fifty years ago with a text that senses the continuities of the aspirations and ever transforming styles and fashions of the city, is striking.

Finally, the Congolese Romanian writer Annie Lulu publishes a stunning text that uses the material aspect of jasper minerals as a metaphor for the experiences of mixed-race children, creating thus a strong and surprising link between the geological history of the country and the biographical narratives that resist binary classifications.

Sandrine Colard (ed): Recaptioning Congo. African Stories and Colonial Pictures, Antwerp, FOMU Antwerp, Laanoo, 2022, pp. 248-249.

The book closes with the images, new captions and stories that emerged in the frame of the work that Colard conducted with people living in Lubumbashi in the frame of the biennale in 2019, highlighting their stories and interpretations on these photographs, and thus actively contributing to writing new captions for photographs representing the Congo: a transformative approach to the (colonial) archive in the perspective of future uses, open to speculation and the wide horizon of the fictional, allowing for many forms of reappropriation and reinterpretation of visual representations by Africans and people of African descent.