In 2022 The National Archives UK embarked on a project to digitise the FCO 141 record series commonly known as the “migrated archives”1 – records from former British colonial administrations. During their conservation assessment, our Conservation for Digitisation team noted that some records bore a label: “A poisonous insecticidal solution has been used in binding this book”. This observation set-in motion a standard internal scientific analysis request, which revealed the nature and scale of insecticide use on administrative records bound for or produced in the “tropics”. Although such practices are well-known and discussed in museum collections, to our knowledge, there was no such precedent in the archive and library sector. The records in FCO 141 were withdrawn from the Reading Room, and over the following five months testing was carried out to determine the nature of the insecticide traces on the records and their potential for harm.

A combination of documentary and scientific work was used to assess the nature of the insecticidal treatment. It revealed many government correspondence records documenting the development of bookbinding with toxic substances, in which agents embedded right into the materials through binding glue. We could also see that insecticides were retrospectively applied in archives and libraries as a pest management strategy. With this knowledge and an occupational health assessment, the documents were made available for public consultation once again, with measures in place to protect our readers. Since that first discovery, and as a result of the research described in this paper, further parts of the collections at The National Archives have become subject to precautionary handling measures: records from British embassies and consuls that deployed insecticides on the administrative documents and libraries whilst they were overseas.

While not exclusively used on documents directly produced by colonial administrations, the geography of the insecticide use is significant. Tropical in its most literal sense is a geographic descriptor tied to longitude, climate and ecologies. However, historians have demonstrated the entanglement of the term ‘tropical’ with judgements about the moral fitness of non-Europeans, and the word’s use to conceptually distance ‘civilised’ locations from ‘uncivilised’ ones (Arnold, 1996). This created a significant difference to the presence of toxic residues on other materials in our collections, such as arsenic-containing pigments used in nineteenth-century wallpapers, and this difference was important to our thinking. 2 Pigments and similar materials used aesthetically were not, as the insecticides, deliberately noxious. Their toxicity was not known at the time they were deployed. Neither were the pigments intended for use in specific geographical regions. They do not carry the same political or ethical legacies.

What follows are personal reflections, by each of us, heritage scientist and historian, on the consequences of this research into insecticide use for our professional practices. They centre on one file of documents from The National Archives’ collections, that produced particularly rich discussion: STAT 14/1180. This file comes from the records of HMSO, the government Stationery Office, in the UK. The correspondence and minutes therein trace extensive conversations from 1927 to 1954, between the Stationery Office, the Crown Agents (the government suppliers agency), the Foreign Office, and several other departments, about how the British government might bind books in ways that would render them resistant to ‘Insect Attack’.

From the Conservation Studio

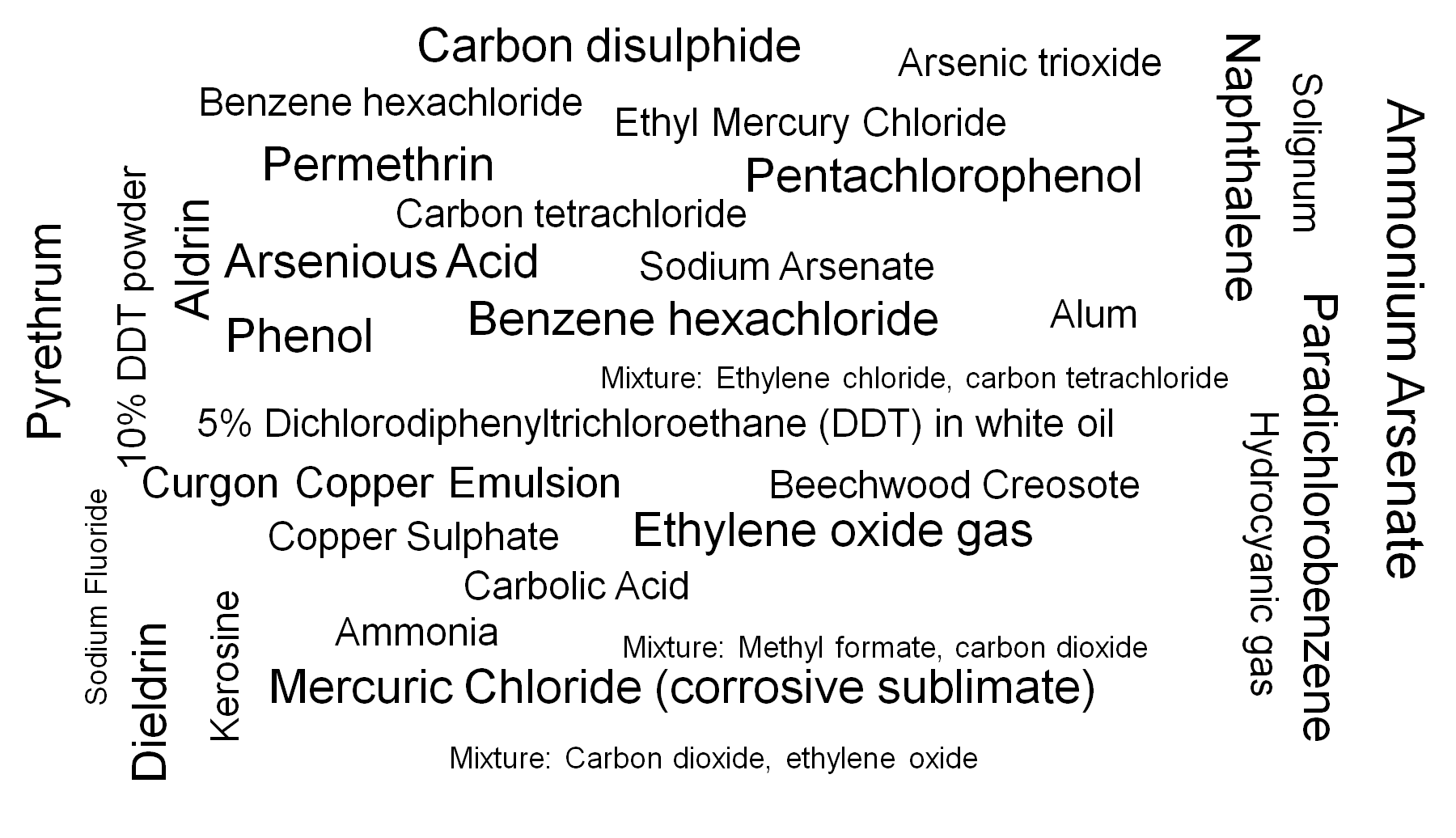

1954: this is the last record I have found describing the use of a ‘poisonous insecticidal solution’, specifically mercuric chloride (e.g. corrosive sublimate) and beechwood creosote, to ward off insects from feeding on books and records in the former British colonial territories. By the 1950s the label served the clear purpose of a warning about the toxicity of the agents used, though this was not always the case. In trying to detangle the complex narrative of why these labels were applied, it seems that initially, they served to reassure colonial administrators of the immunity of the paper against the ‘ravages of insect pests’ – an evolution in understanding and practice characteristic of the general use of pesticides.

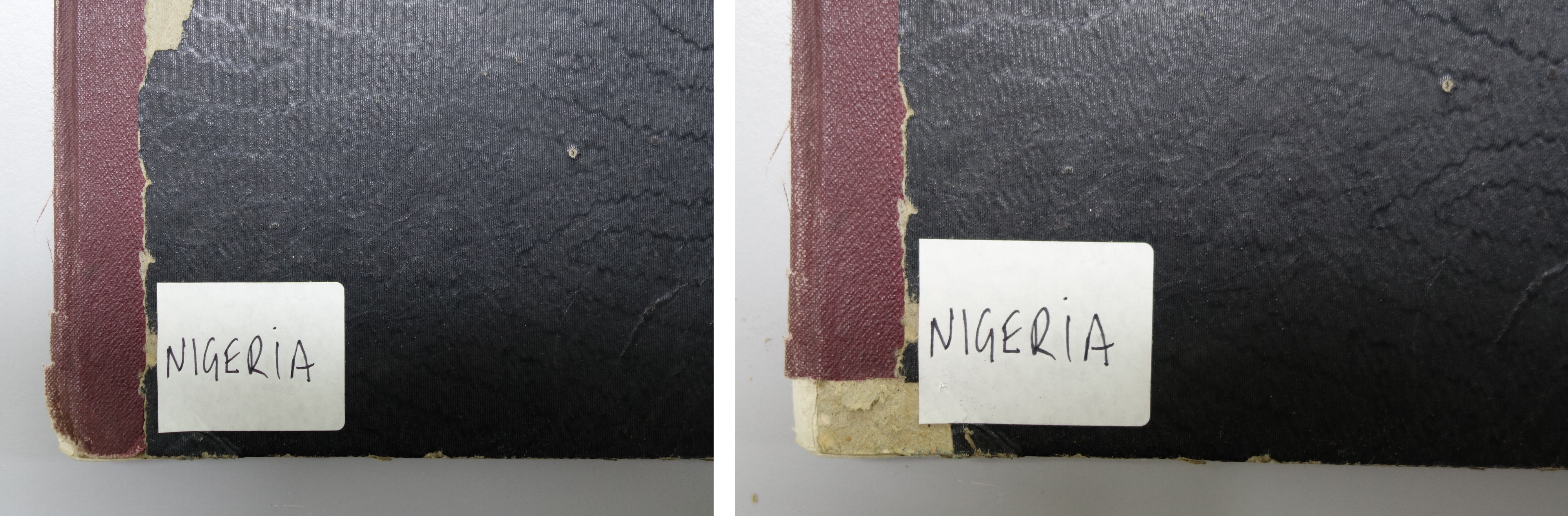

It was such a label in a 1943 register of outgoing telegrams from Nigeria that first alerted us that some of our records may be hazardous to handle and use. And the records were very much used: from the publics closely reading and tracing their histories, to the conservators meticulously mending small tears and the imaging operators preparing and scanning each page.

Fig. 1: The National Archives record FCO 141/13421

As a conservation scientist in the archive, I set-up the x-ray fluorescence spectrometer,3 talked to my colleagues dealing with contemporary, integrated pest management, and began to analyse the records.

No one at the archive had any knowledge of the historic practice of binding books with poisonous solutions. Our institutional and professional memory was blank.

Before this analysis request, I had never heard of the ‘migrated archives’. I did not know there were contested records in the repositories or that there were communities asking for their restitution (Lowry 2023). Of course, I knew about NAGPRA and the Benin Bronzes, but I did not know about the Crown Agents for the Colonies or the Colonial Insecticides Committee Research Unit. I had never learned what the acronyms in the catalogue descriptors stood for: CO (Colonial Office); HMSO (His Majesty’s Stationery Office); CAOG (Crown Agents for the Colonies and Crown Agents for Oversea Governments and Administrations); FO (Foreign Office), FCO (Foreign and Commonwealth Office). In heritage science, we talk about ‘silos’ between materials scientists and (art) historians… but a silo is too mild a metaphor to describe the chasm that was looming between me and historical research.

As the analytical data accumulated, my pile of books and papers on the history of pesticide use in museums also grew – libraries and archives were never mentioned in these accounts. The toxic agents were retroactively applied during ‘acquisition’, in the museum storeroom or display case; never in the creation of the object itself.

The suggested solution: restrict access; wear full Personal Protective Equipment including FFP3 face masks, nitrile gloves, HazMat suit or sleeves, view only under fume extraction, clean with HEPA filter vacuum (Angelova, 2023). And always, the persistent “little information exists about these practices”; “such practices were so common and widespread that records were not kept”.

The labels in our collections told a different story: the books were bound with the poison right inside, and a 1953 research paper (Bracey & Barlow) disclosed that this was not only common practice, but a government-researched, specified and mandated process for notebooks, registers and books being sent to the colonies. Systematic experiments on binding methods were alluded to, and the biocides tested included mercuric chloride, DDT, Aldrin, Dieldrin, and Lindane.

I won’t lie – the typical research-driven excitement and relief flooded over me as I realised that these government guidelines were archived in our own repositories.

I had spent five years working in the archival conservation studio, but I had never read the content of our records. I had only interrogated their material narratives – their elemental composition, their molecular degradation pathways, the stable isotopic composition of their lipids. The sole purpose of my work was to make a case for material preservation and access through insisting that materials tell stories; that the structure of the record is as relevant a carrier of content as the content itself. I had not considered the lines of historic and sociopolitical inquiry that materials can further open, nor the shift in practice they could affect. I made my first order as a reader:

CAOG 12/87 & 12/88: Preservation of Books etc. from ravages of tropical insects Vol. 1 1907-1935 & Vol. 2 1936-1951.

In scientific research, you always have the sense that you are discovering something new. Sure, you build on existing research, but ultimately, everyone is on the quest of synthesising a new compound, describing for the first time a biochemical mechanism or a degradation pathway… Suddenly, I found myself in a new-to-me epistemic paradigm: trying to piece together the past, to write a history of an existing practice, to summarise and pull together extant (but incomplete) information into a cohesive narrative. It was not long before I also became acutely aware of the significance and history of this record series.

I became obsessed with trying to find the beginning – when did these practices develop, by who, where, why? Inevitably, every time I thought I had discovered the ‘first instance’ I would come across a new letter, manual, or study that described everything I had dug up and pointed to an even earlier source.

The list of record orders grew further :

-

- CO 323/1201/13 The use of a mercuric chloride solution in book-binding to prevent insect attack

-

- CO 323/1406/1 Prevention of insect damage to records in the colonies

-

- CO 323/1520/5 Prevention of insect damage to book binding

-

- STAT 14/1180 Binding of Books to resist Insect Attack

-

- AY 4/900 Books and documents: preservation from insect attack in the tropics

-

- DH 72/395 Insect infestation

-

- DSIR 36/1724 Insect Pests of Books: an annotated bibliography by C J Golledge, Librarian, Imperial Bureau of Entomology

While writing this reflection, we may have found it – the master-source: William J. Plumbe’s 1959 Preservation of Library Materials in Tropical Countries. Plumbe nails the inception to 3,000 years ago: to the Apocryphal books of the Bible, to Pliny the Elder and Horace. I wondered if we’d find cedar oil on the El-Hiba papyrus?4

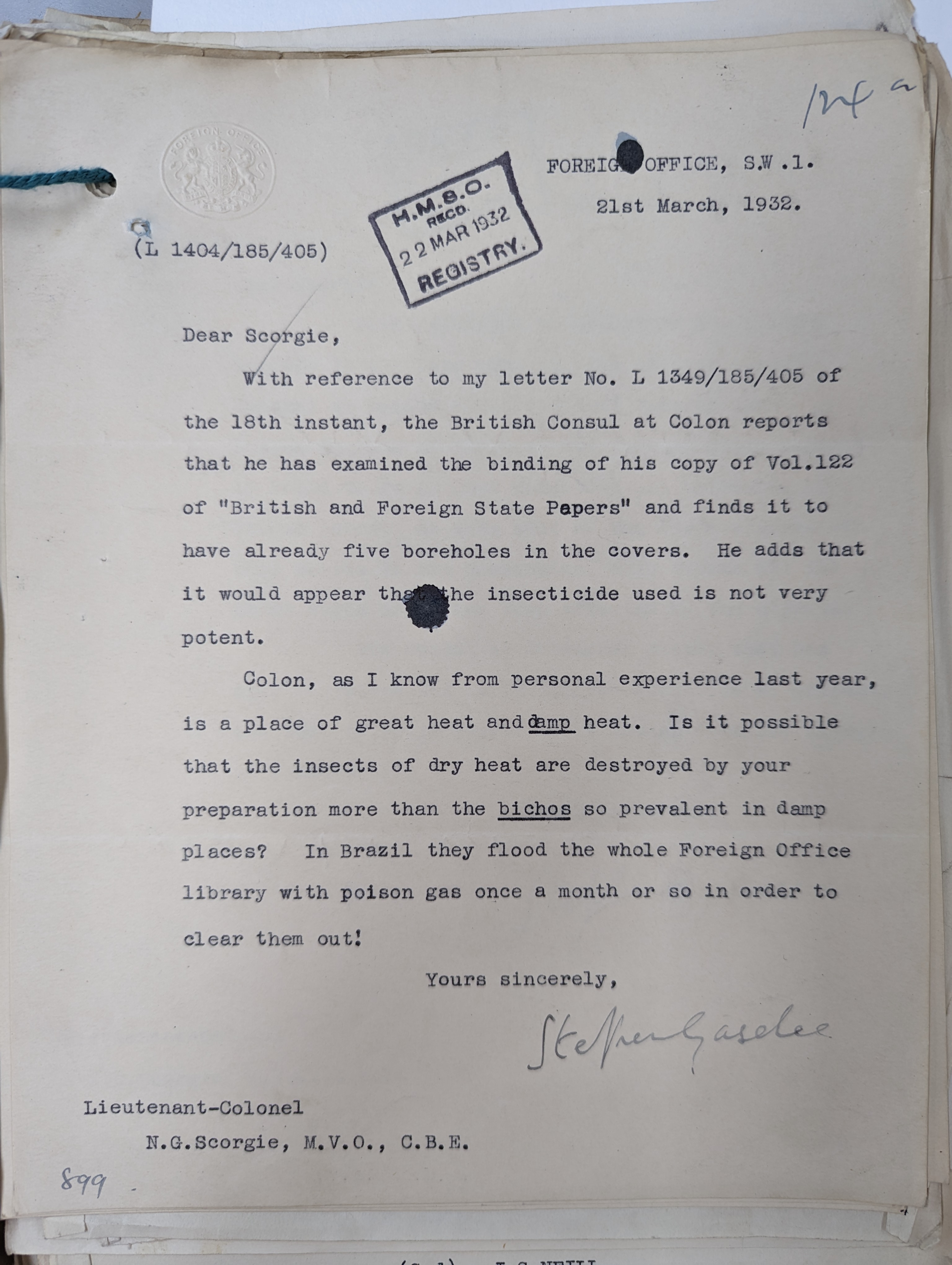

Plumbe’s impressive list of poisons for the preservation of books covers more than 70 mostly natural agents, and many more of the modern synthetic biocides of his time. He not only aims to demonstrate what is (and had been) standard professional practice in book preservation, but also to outline the mid-century cutting-edge methods. Though based at the University of Malaya, he surely must have had an insider contact at the British Government – Plumbe summarises nearly every practice mentioned in the stack of correspondence records on my desk.

As the information accumulated, I was struck by how rapidly and completely past professional practices can become not only obsolete but completely forgotten. The invisible nature of the applied agents must have only accelerated this process.

After we finished our initial analyses and published the data, we heard from colleagues abroad: the use of pesticides on documents and books seems to have been common, though not discussed openly in many institutions.

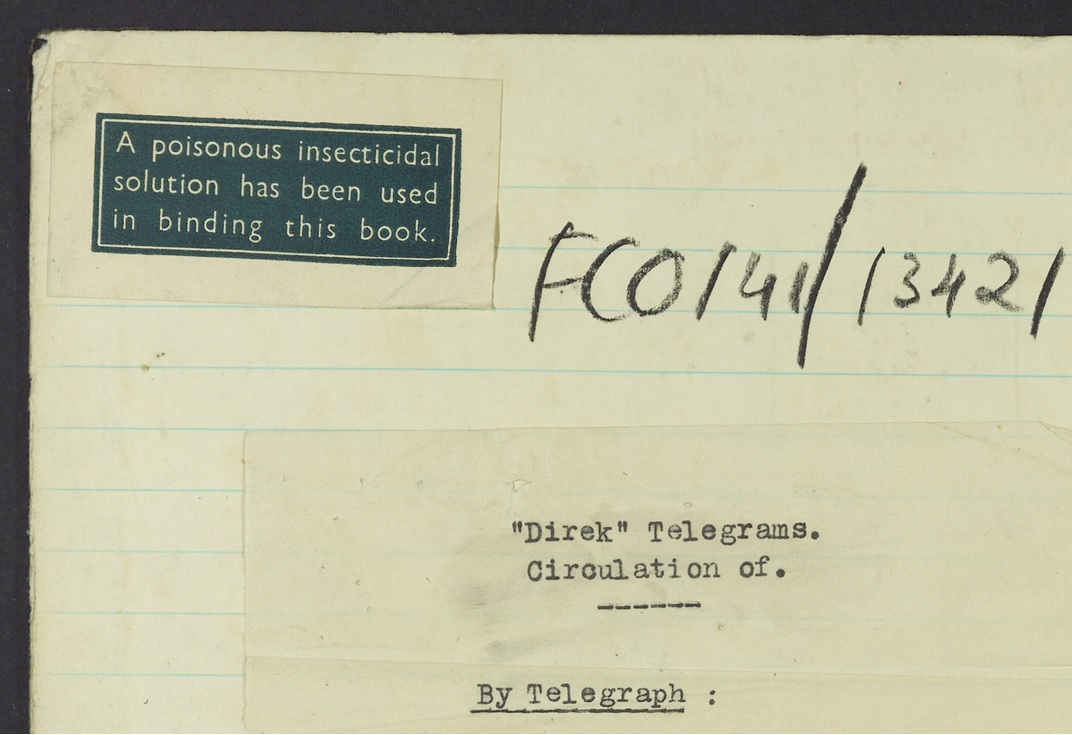

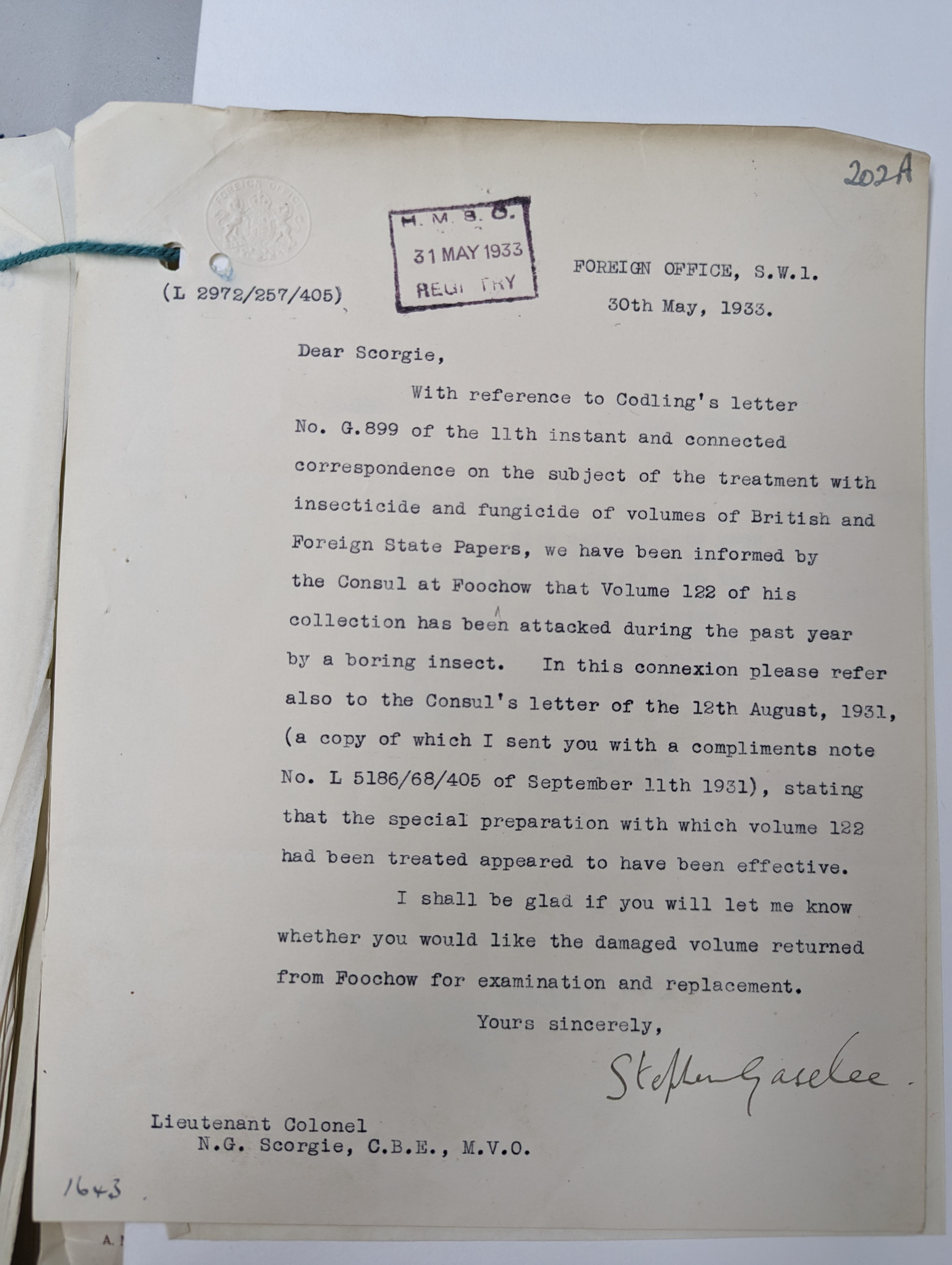

Fig. 2: The National Archives STAT 14/1180/124a: S. Gaselee (FO Library) to N.G. Scorgie (HMSO) 1932: “In Brazil, they flood the whole Foreign Office library with poison gas once a month or so in order to clear [the bichos]5 out!”

Colour-coding my notes – red for a toxic agent, yellow for a geographical location – I began to catalogue the early 20th century (colonial) Librarian’s chemical arsenal. At least since 1888 the British Consulate in Shantou, China, was applying the mercuric chloride mixture to books and records. As a material scientist, I could trace and recount each element, molecular compound, and proprietary agent. Should I list them in alphabetical order? Group them as gases, liquids, solids? According to their level of toxicity? Present them as a cynical WordCloud?

Fig. 3: Chemicals mentioned in STAT 14/1180 as being applied as insecticide to books and documents.

Between mine and Plumbe’s lists, we may have something that rivals the 90 agents used on museum objects in Odegaard’s Old Poisons, New Problems (2005). For books and records, however, there are more proprietary agents to add:

-

- Deleoil (likely similar to early FLIT (unknown author, 1931)

-

- FLIT (1920-30s – methyl salicylate in kerosine (Fisher & Bailey 1929, 225), 1940-50s – 5% DDT)

-

- Flytox (1920-30s – pyrethrum and methyl salicylate in kerosine (Ibid) later – DDT)

-

- Keating’s Powder (extract of pyrethrum)

-

- KOMO Fly Liquid No. 2 (“similar to FLIT”, with a “smell [that is] less offensive”6)

-

- Ratinspray (“similar to FLIT and KOMO”[^7]](https://troublesdanslescollections.fr/2024/07/01/insect-enemies/#_07))

The records, and our test results, confirmed that the pesticides were not just used in creating the books and ledgers, but were also liberally applied to them later.

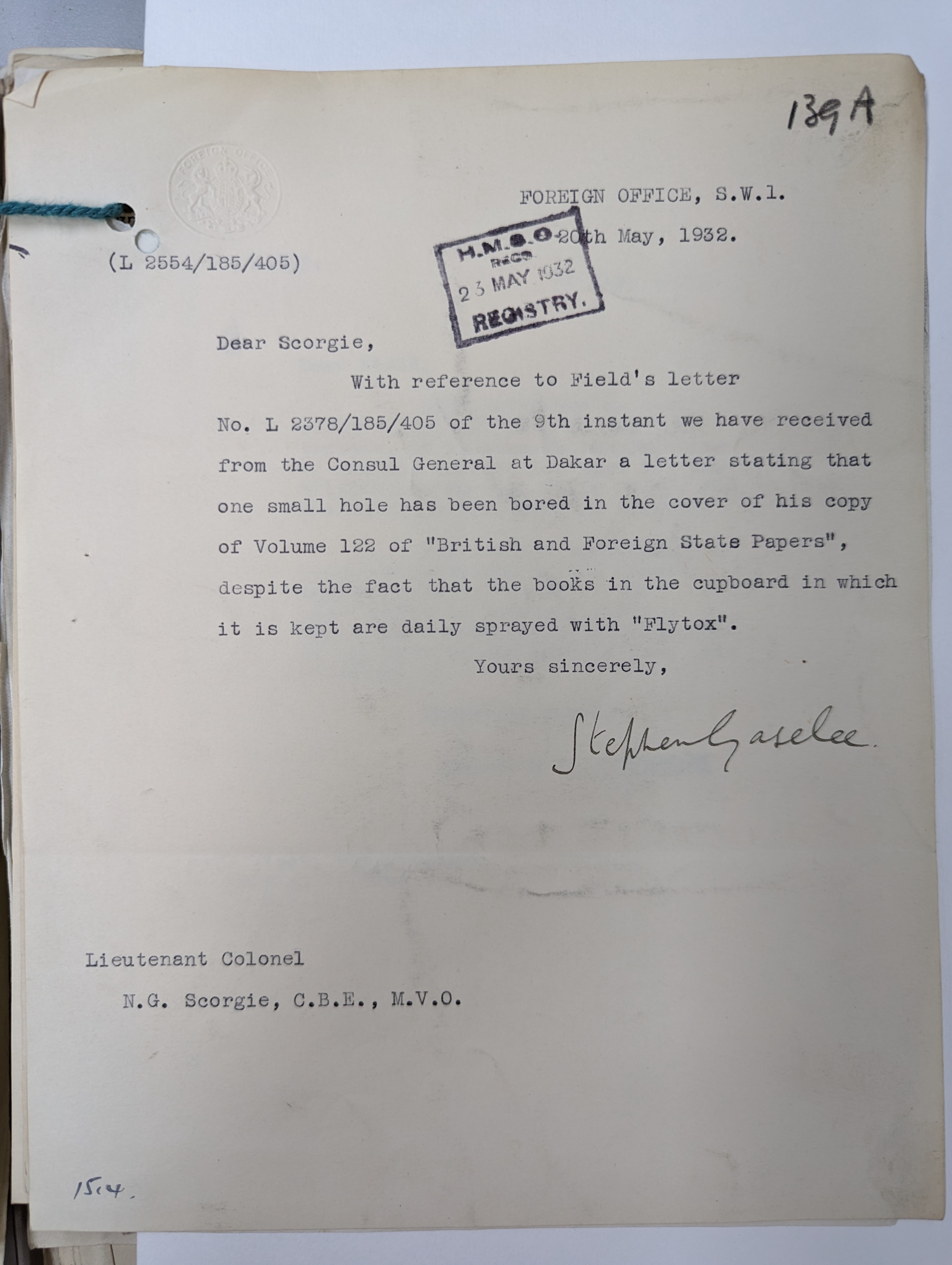

Fig. 4: The National Archives STAT 14/1180/139a: S. Gaselee to N.G. Scorgie 1932: “the books in the cupboard (…) are daily sprayed with “Flytox”” recounts the Consul General in Dakar.

Kerosine and other petroleum derivatives were common: “Local [Bahia, Brazil] libraries adopt the expedient (sic) of occasionally dipping their volumes in a deep vessel containing kerosene – rather a drastic remedy.”7 The College of Pestology Inc. provided their own formulation, which was widely adopted by HMSO and several consulates: “Paradichlorobenzene ½ lb dissolved in paraffin 40 oz. To this saturated paraffin add oil of PXX (tar) ½ oz, Petrol 6 oz, 2 oz of carbolic acid. 2 oz oil of lemongrass”.8

The correspondents seem unphased by the combustible nature of these formulations, but maybe that was par for the course – after all, carbon disulphide, seemingly the most common library fumigation method mentioned, came with a warning of leaving a highly explosive atmosphere after treatment.9

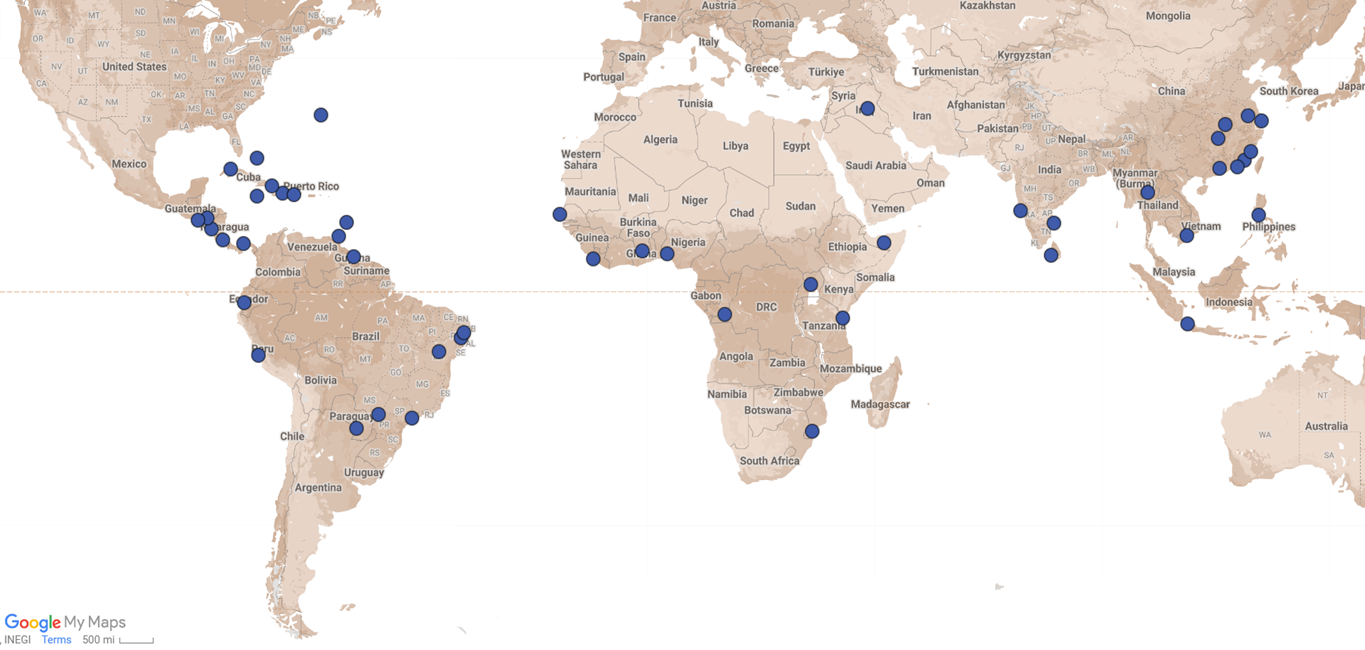

In STAT 14/1180, advice and experiences are exchanged across a global network of actors, the Public Record Office, binding works, laboratories, private research institutes, museums and libraries, the CO, HMSO, CAOG, FO. How to represent these tangled webs of insecticidal practices? I could map all the locations in my yellow-colour code. I could try to connect the dots but what would these lines even reveal?

Fig. 5: Locations of consuls where insecticide-treated test notebooks were sent and locations where records with warning labels were seen by FO library correspondent.

Moses might have advocated for anointing holy books with cedar oil but T.E. Thorpe’s 1907 guidance is directed specifically at government records. The communications indicate that for decades, colonial administrators and consuls around the world undertook semi-official experiments on bound books and records to find the best agent with which to destroy various insects;10 the lowest necessary concentration of it; the best method for its application. Added to this, a series of tests on different types of binding boards, cloths, and colours, varnishes, pesticide-impregnated paper, storage containers, shelving, and fumigation strategies.

The motivation for the application of poisons to records seems to shift constantly but the general sense is one of defensive urgency. The terms “warfare”, “ravages”, “enemies” used in nearly every letter, and the ever-expanding list of agents left me with a sense of frenzied bloodlust (not so much a preservation imperative), a feeling that both the contents of the records and their readers were left by the wayside in an feverish quest to decontaminate the library.

Sometimes, the records are described as utilitarian content-carriers and the insect damage is seen as detrimental to contemporaneous users. Often though, long-term material integrity is paramount: there is concern over the greenish hue imparted by the less-toxic Copper Curgon Emulsion; warnings to always avoid the application of mercuric chloride to gilt lettering; different types of calf-skin binding would require custom treatment that could only be carried out by HMSO in Britain. In the quest to save it from the ravenous ‘Tropical’ insect pest (Deb Roy 2020; Hofmeyr 2023), the government record demanded the same level of protection as a treasured, ancient manuscript. Yet unlike rare books, records could be experimented on, field-tested, “nibbled on”,11 printed and re-printed. It was not field collectors, museum aides or conservators but bureaucrats choosing what to preserve and how.

I was struck that, similarly to objects bound for the museum, the insecticides were applied to enable use of the records by colonial officials or British audiences. And unfortunately, like many of these objects, it is contemporary users around the world that must grapple with the legacy of these practices.

The value frameworks applied to materials in the archive are still decisively fluid: bound to context, user, technology, age, politics. In the conservation studio, every material encounter is meticulous and considered even when the task is to prepare a record for digitisation and render that same venerated materiality potentially ‘irrelevant’. The toxins on these records exposed this paradox completely.

Physical access to the series was restricted while we carried out the testing and there was a palpable urgency to ensuring this was a very temporary measure (Banton 2022, 2023). The migrated archives are a critical resource to our society, and, considering the destruction of many such records (Sato 2017) their physical accessibility is paramount (Maina 2021; Lowry & Chaterera-Zambuko 2023). In the laboratory, I agonised over sampling the binding for analysis – each area was carefully documented, each material loss felt alarming. The focus was on the readers, their safe access to the material records justifying each excision. Yet in the back of my mind, I knew that we had first seen the poison warnings during a conservation for digitisation survey. Though digitisation is assumed to augment and supplement access to the collections (Balachandran 2022), I wondered if their newly acquired ‘hazardous’ status would lead to a limited contact with their material manifestation. In the process of establishing how to safely handle and touch the records we were also enabling their safe digitisation; the missing bits of textile or adhesive from the book spine completely irrelevant to their new status as data.

Fig. 6: The National Archives FCO 141/13428 before (left) and after (right) sampling for insecticide residue analysis

Gloves and other safety measures are now mandatory when touching this record series. In contrast to the alienated contact with toxic repatriated ritual and community objects, our readers seemed mostly unphased (Banton 2023). Access reinstated, the content of the records is once again central, the material structure receding to the background, to just a medium for information.

Elizabeth Edwards described the process of ‘making paths’ in archives, as “as a metaphor for the processes that have, in recent decades, transformed the archival accruals of the colonial from being moribund deposits of past practices and ideologies to being vibrant spaces of contested histories and multiple subjectivities” (Edwards 2022). The material presence of the FCO 141 series and the ‘toxic afterlives’ (Arndt 2021, 2022; Etienne 2022; Bangstad 2022)of the colonial administrations’ record protection habits forced me and my colleagues to turn a critical lens on our work. The analytical and historical lines of research that these chemical traces provoked, like “pathways cleared through the archival undergrowth,” have exposed the glaringly political potential of archival conservation. In critiquing the scientific approaches (or encroachments) of these bureaucrats to record preservation, I also came to question the place of contemporary heritage science in the archive.

Material encounters with colonial records force archival conservators and scientists to confront the socio-political implications of the records we treat and analyse. Similarly to the conservation and repair of heritage sites, it is when these records require treatment that we are forced to discuss the political regimes that created them in the first place, the economic and social collapses which led to their current state, and which records receive attention and which do not (Stuchel 2019). The materials – records and toxic agents – have launched myriad paths of inquiry: scientific, historical, political, practical, methodological – allowing conservators and heritage scientists to reframe our work from neutral to rich with potential for connection and introspection.

From the Reading Room

Over the past few months I have joined Lora in this exploration of the history of insecticide use on our records. As she outlines above, we have read files from different decades and different departments. Of all of these, I keep returning to STAT 14/1180 in my mind. The file contains a particularly rich account of discussions around the ways in which the UK government approached preserving records from the ‘ravages of insects’. It explores the material limits of the book and bound records as technologies in the twentieth century, and the ways in which insecticides extended and altered the possibilities of that technology in executing political projects (Deb Roy, 2020; Hofmeyr, 2023). Pragmatically, the file detailed particular episodes, policy decisions and internal discussions that helped to identify typical insecticidal practices. However, the reasons that this file resonated with me, I think, sat somewhere else. After reading and re-reading these abstracted administrative exchanges about the use of insecticides on books and records, the vocabulary and anecdotes started to take on an allegorical, almost mythological character. From STAT 14/1180 we learned how poison can be deposited in different parts of a book’s anatomy. If the poison was hidden in a book’s spine, then its deleterious action remained dormant against humans.12 If someone committed an outrage to the book, if a malevolent or ignorant reader attacked the book’s essential construction, then like a demon, the poison could be awakened.13

The world of those early twentieth-century civil servants was one which dreamt in hierarchies, locked rooms and order. Only certain people entered these domains of zinc-lined boxes, steel shelves, and mahogany. Aside from conducting “war on tropical insects”, these knowledge spaces, at the heart of British diplomatic missions, were also guarded against infractions by those of the wrong nationality, the wrong class and especially, the wrong race (Southern 2020; Southern 2021).14 Children, of course, were not permitted, their entrance in these sophisticated labyrinths of paper bringing the risk that a poison book might be eaten, with potentially disastrous consequences.15 One book fortress in Guangzhou came under siege in 1941. The doors were bolted, and the books only re-emerged when global conflict came to an end in 1945, providing an interesting case study for the bureaucrats on the longevity of protection the mercuric chloride could offer.16

Fig. 7: The National Archives, WORK 55/2. The consulate at Canton [Guangzhou] in the early twentieth century, caption “Canton – offices and assistants’ quarters. Main building – south side first floor. Second V.C’s [Vice Consul’s] verandah [sic] from west end.”

At other times the books were also cared for with patterns of attention that sound almost mystical, and that gives the books a quality of liveliness in my imagination. Bureaucrats discovered that there was sometimes a contradiction between locking books up and keeping them safe, “Light and Air are both held to be inimical to animal pests”.17 We learn from the correspondence that in some instances the books seemed to be protected by regular use, and the frequent consultation of the books became a duty to them. Sometimes the ’use’ of books could take on a ritualistic character as when (again in Guangzhou), the consulate’s books were brought outside to be aired in the sun, in dry weather, on frequent rotation (one can imagine, perhaps, on the veranda at the consulate in Fig. 7) .18

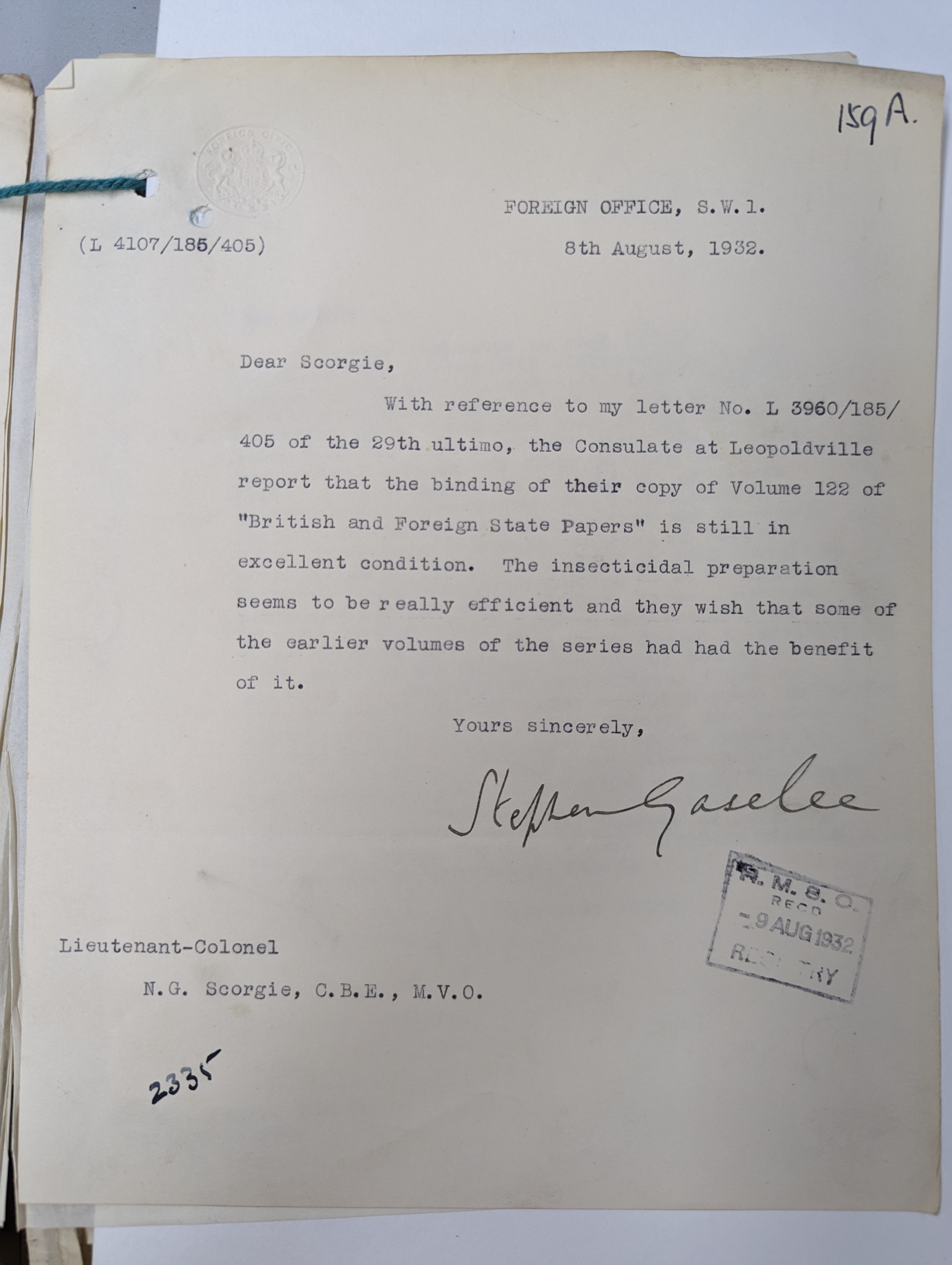

In a series of bureaucratic experiments that started in the 1930s and went on into the 1940s, multiple copies of “British and Foreign State Papers, Volume 122” imbued with different insecticidal properties were distributed around the world. The trajectories of these books in locations from Brazil to Tonga, and their encounters with insect “enemies” echo the traditional stories in which brothers, or sisters, set out from their homes on quests which test or prove their different qualities.

Fig. 8: The National Archives STAT 14/1180 159a: S. Gaselee to N.G. Scorgie 1932: “the Consulate at Leopoldville reports the binding of their copy of … is still in excellent condition”.

Fig. 9: The National Archives STAT 14/1180 159a: S. Gaselee to N.G. Scorgie 1932: “we have been informed by the Consul at Foochow [Fuzhou] that Volume 122 of his collection has been attacked during the past year by a boring insect”.

In the last two decades historians and anthropologists have reminded us of something of which the authors in STAT 14/1180 were obviously well aware. Government information practices rely on social convention as much as technological innovation (Bayly 1997; Hull 2012). The survival of records and information is built on vast conceptual systems that simultaneously organise the presence and value of different forms of human and non-human life (Mbembe 2019). The documents at The National Archives record centuries of British intervention around the globe, through periods of global economic domination and colonial exploitation. As many scholars have described, our collections reflect the ways in which book-keeping and correspondence served to scaffold those military, economic and political regimes, even if the specific histories in our collections constantly surprise me (Lester et al. 2021; Siddique 2020).

I don’t understand, in the way that Lora does, either the chemical or physiological significance of each item in the litany of poisons that are mentioned in STAT 14/1180. The specificities of their actions on bodies are important, I resolve to learn more. Even without that detailed knowledge, however, the sense of these insecticidal treatments as poisons, brings a new sensibility to my work with the records. It reinforces a perspective that highlights the materiality of the archive, emphasises human touch, and the architectures that determine access.19 Focussing on real and imagined points of contact between paper, glue, hands, and mouths (of children or insects) radically reframes what an archive is, did, and does. The word ‘poison’ brings to the fore the ways in which an archive is a set of journeys of particles in and out of bodies and through ecosystems.

Viewing our collections from this perspective feels vertiginous. The discovery of the insecticide residues had practical implications for the way we store and handle those records. These have been addressed through forms of barrier against the transfer of chemicals: gloves and boxes. However, even with those practical problems resolved, more general questions about the relationship between archival records, and environments remain in their wake. Perhaps that is why bringing allegory to explore the descriptions of touch, safety, poison, and journeys in twentieth-century bureaucratic discussions seems to have something to offer. That reading, and those terms, might be more vivid ways to begin public conversations about archive collections that acknowledge the archive as a process of continual physical exchange with people and with places.

Those acts of imagination are not apolitical. Some of the metaphors I’ve used here are part of everyday usage with those who handle paper records. Historians have explored the significance of the book’s extensive metaphorical universe: with physiological and social references, from ‘bodies’ of text and ‘spines’, to the gendered implications of ‘widows’ and ‘orphans’ of the printed paragraph (de Bondt 2020; Gore 2023). Recently it has become more common to draw more direct analogies between the human body and paper archives as parallel sites of memory (Taylor 2003). Imagining sets of records as family members, archives as fortresses, books as holding demons, takes a longer step away from common practice in collections management. I can see the risk of romanticising the experience and consequences of physical, social, environmental harm.20 However, I hope that allegory might orientate us more directly to the social conventions that govern our archival practices in the present. They challenge me to consider more carefully which of our contemporary processes are functional and which are ritual (Diamond 2008; LaCapra 1985). Drawing out the allegorical resonances from STAT 14/1180 might help to navigate the pathways that Lora describes.

For all these reasons, the word ‘poison’ does better work than insecticide, or even biocide. While other toxic substances that have ‘emerged’ unexpectedly in archival collections (such as arsenic in wallpapers) were accidentally toxic, here their toxicity was fully intentional and is associated with particular historical political projects. The word poison speaks directly to the potential implications of these substances for human relations and negotiations about the historical record. It re-emphasises the issue of care in our custodianship of records in every sense.

-

The International Council on Archives Expert Group on Shared Archival Heritage defines, ‘migrated archives’ as archives removed from the place of their creation, where the ownership of the archives is disputed by two or more parties. The records held in the series FCO 141 originate from 41 territories that were formerly British colonies, and some records within it are the subjects of restitution claims. Please also see the catalogue entry for FCO 141 in The National Archives, UK. ↩

-

Some wallpaper samples in registered designs (BT 43) contain low levels of arsenic in colorants. https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/x-rays-wallpapers-hunt-arsenic/ ↩

-

This, and other analytical instruments, are used to detect and identify the molecular and elemental composition of cultural heritage materials (e.g. arsenic, mercury, lead and other toxic elements in this case). ↩

-

The El-Hiba papyrus held at Graz University, Austria, was recently hailed as the oldest book ever discovered, dating to 260 B.C. ↩

-

Emphasis in original; Portuguese for vermin. ↩

-

STAT 14/1180/44a (1928) ↩

-

STAT 14/1180/151a (1932) ↩

-

STAT 14/1180/53a (1928) ↩

-

CAOG 12/87 and STAT 14/1180: T.E. Thorpe (Principle Chemist), Enclosure in Circular dated 30th April, 1907: Government Laboratory. ↩

-

Of primary concern are cockroaches, various boring beetles, termites, silverfish, and book worms ↩

-

COAG 12/87/9 “Report on dummy volumes received from the Crown Agents for the Colonies” 1935, Dept of Agriculture, Peradeniya, Ceylon ↩

-

290, 3/11/1954. HMSO minute drafting letter to the FO Press. ↩

-

The unbinding of books for conservation processes was possibly not envisioned by the twentieth-century bureaucrats who contributed to this file, their unbinding for digitisation, certainly not. ↩

-

48a, 1/11/1928 Copy of letter from Codling (HMSO) to Gaselee (Librarian, FO). On histories of (lack of) participation in British diplomacy in this period for those other than the White upper-class, see James Southern, ‘Black Skin, Whitehall: Race and the Foreign Office’, 2nd Ed. London: FCDO History Notes, 2021; James Southern, ‘Social class and the Foreign Office, 1782-2020, London: FCDO History Notes, 2020. ↩

-

157a, 11/08/1932. Copy of letter from Scorgie (HMSO) to Gaselee (Librarian, FO). As a side note, children are not allowed in the reading rooms of The National Archives today, except under exceptional circumstances. ↩

-

285b, 3/05/1946. Copy of letter from the British Consulate General, Canton [Guangzhou] to the Library, FO. ↩

-

81, ‘Precis of Replies from West Indian Colonies on the subject of Protecting Official Records from the ravages of animal pests’ (1907), enclosed in a letter of 29/11/1929 from Scorgie (HMSO) to the Government Chemist. ↩

-

256a, 19/11/1935. Letter from Gaselee (Librarian, FO) to Scorgie (HMSO) ↩

-

This applies to an archive in both its paper and digital form (Balachandran, Ibid.; Parikka (2013). ↩

-

As evidenced by a long history of the use of figurative speech in colonial discourse to dismiss and dehumanise opposition as Kolb 2021.y historical mistreatment or appropriation of indigenous cultures, the adoption of indigenous conservation practices represents a crucial step towards reconciliation and healing. Such a step is fundamental in recognizing past injustices and taking concrete measures to rectify them, by allowing communities to co-conserve and rewrite their own history through practices, documentation, and contextualization. ↩