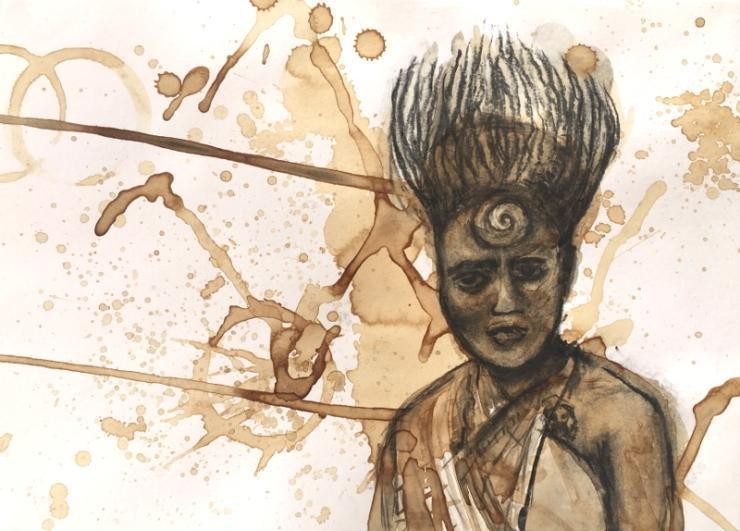

Fig.1: Video still from sketchbook for “Queens of the Seas”: Coffee, pastel, pen and marker drawings produced as part of my research on Namatuco, Patihina, Muzamussi, Maxaxa, Xesipe, Dabondi and Fussi—the seven wives of inkosi Gungunhana, captured by Portuguese forces at Chaimite in 1895 (2017–2021). First pages show sketches made whilst watching “Chaimite” (Dir. Jorge Brum do Canto, 1953). Video: Sketchbook studies for #QueensOfTheSeas #RainhasDosMares

Perhaps one of the biggest questions that I ruminate over at present is: who is speaking/writing, in what capacity, and with what ‘baggage’? It is not to try to judge some researchers or creatives as more authentic due to their belonging to a certain group or space, but it is to attempt at an unpacking of all the filters and biases that could influence one’s thought, and by consequence, the content of the text itself.

I have had to understand my current research as an infinite work-in-progress, as I try to find balance between research and ‘authentic’ art-making. Here I employ the term ‘authentic’ in the simplest of ways that I was taught by my historian father - to experience art in a way that it moves and elicits an emotive reaction from the viewer. This is to say that a viewer should not need to be pre-prepared with academic or other knowledge before looking at the art in order to feel, and dare I say, understand it.

Fig.2: Digital reproduction of a postcard depicting inkosi Gungunhana and his seven wives in Lourenço Marques in early 1896, prior to their deportation to Lisbon. Source: Nhapulo, T. J., História–12th Grade, 2019. Plural Editores. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Figura-8-O-imperador-Gungunhana-e-as-suas-mulheres-Fonte-De-Historia-12-classe-p\_fig7\_367825966

When I first came across the story of Gungunhana, his capture and subsequent exile on Terceira island, it was the apparently missing narrative of the amakhosikazi1 Namatuco, Patihina, Muzamussi, Maxaxa, Xesipe, Fussi and Dabondi that marked me most. Frustratingly, I have found less on them in document form, relying primarily on the few group photos that others have found in their research.2 The few individual photographs of these women are either totally untitled or hold a caption such as “Gungunhana’s favourite”, leaving one to speculate who this could refer to, and even if she appears again in the group photos. To note that there were in fact three more women in the larger party that was imprisoned and exiled in Portugal: Pambane, Oxoca and Debeza. They were wives of Nwamatibejana (Zixaxa), but for now my research focuses on the seven amakhosikazi first mentioned as there are considerably more photographs of them.

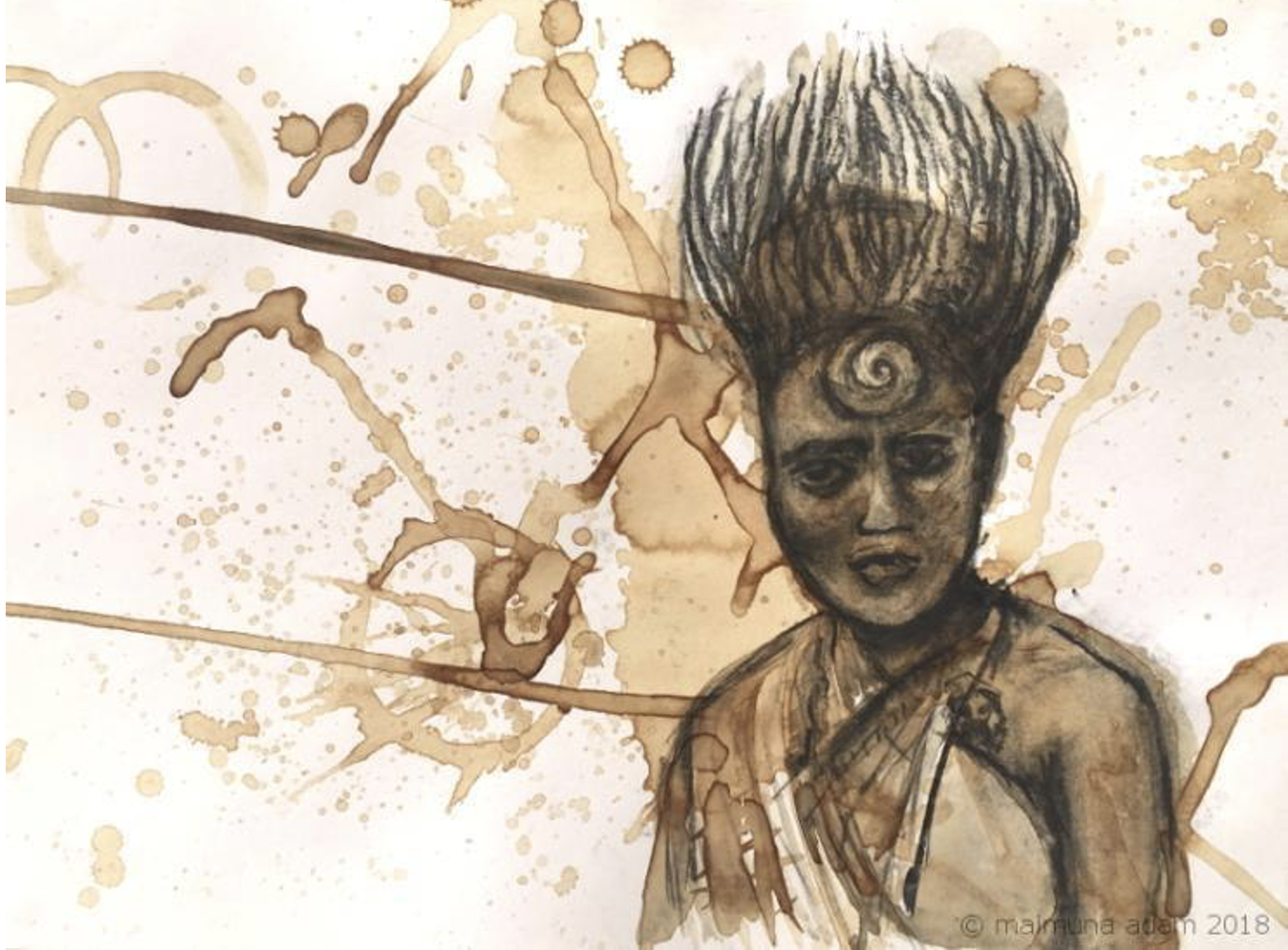

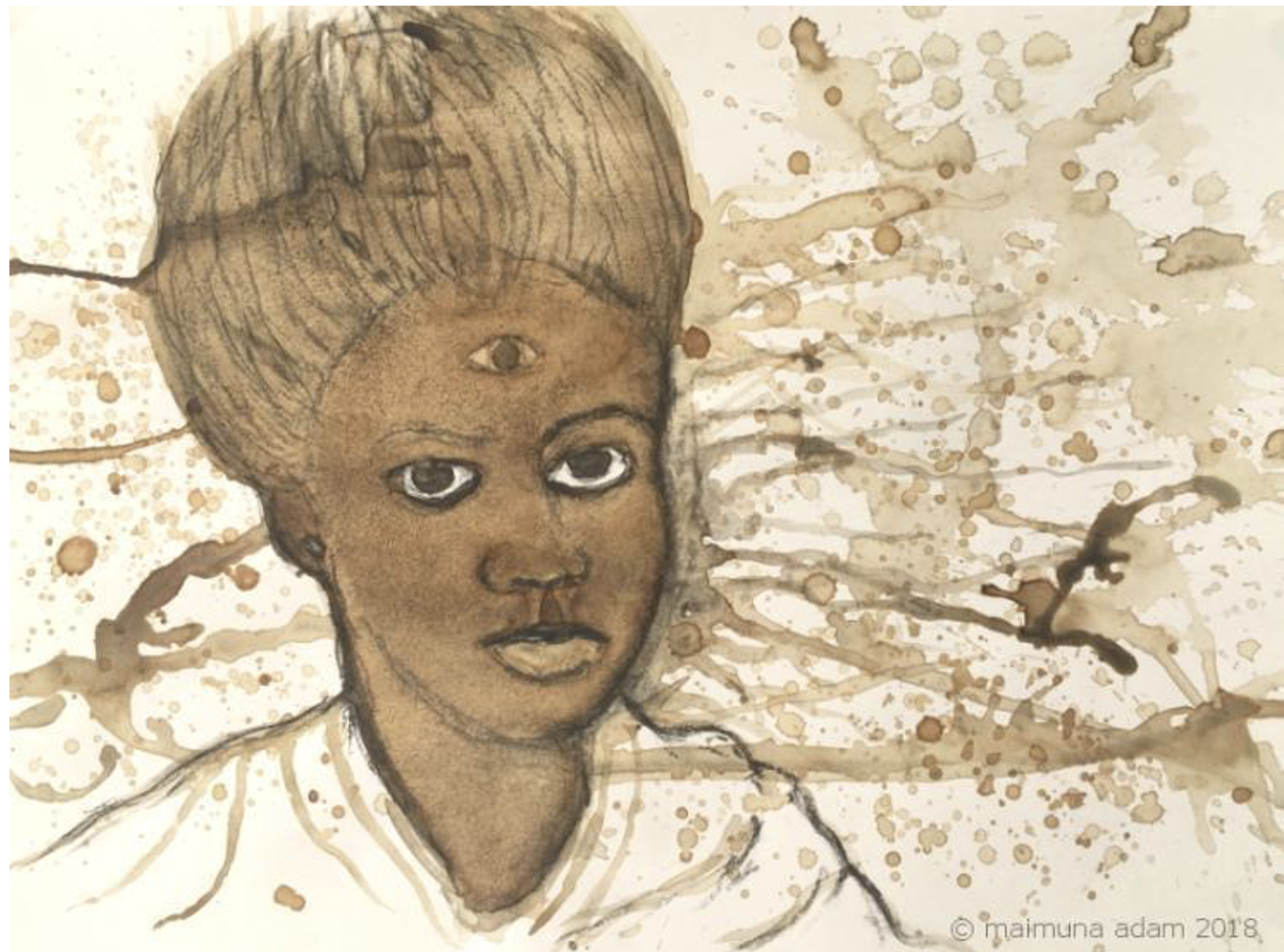

Fig.3: “Queens of the Seas-Inkosikazi III”, 2018. Coffee and charcoal on watercolour paper by Maimuna Adam.

Spirituality, or a sensitivity to energy, is a language I am reading everything from at the moment. This is particularly true if I reflect on the hours spent since 2018, when the seeds of this project began, looking at the few grainy digital copies of photographs I have found of some of the amakhosikazi. These, coupled with the invaluable research that Maria da Conceição Vilhena has presented in her books Gungunhana no seu Reino (1996) and Gungunhana : grandeza e decadência de um império africano (1999); as well as novels Ualalapi (1987) and As mulheres do Imperador (2018) by Ungulani Ba Ka Khosa; Mulheres de Cinzas (2015), A Espada e a Azagaia (2016) and O bebedor de horizontes (2017) by Mia Couto, and Jorge Brum’s film Chaimite (1954) have informed this project. These–plus talking to people directly, hearing them recall family stories or rumours that have been passed down to them, or reading public comments on Facebook related to the topic of Gungunhana and the larger group’s imprisonment and exile to Terceira and São Tomé islands–have been instrumental in trying to visualize the amakhosikazi and their imprisonment, exile and return, for those that survived: that would take all of them from today Mozambique, to Portugal, and then São Tomé Island, and some back in 1911.

Fig.4: “Queens of the Seas-Inkosikazi IV”, 2018. Coffee and charcoal on watercolour paper by Maimuna Adam.

The coffee bean as a primary source

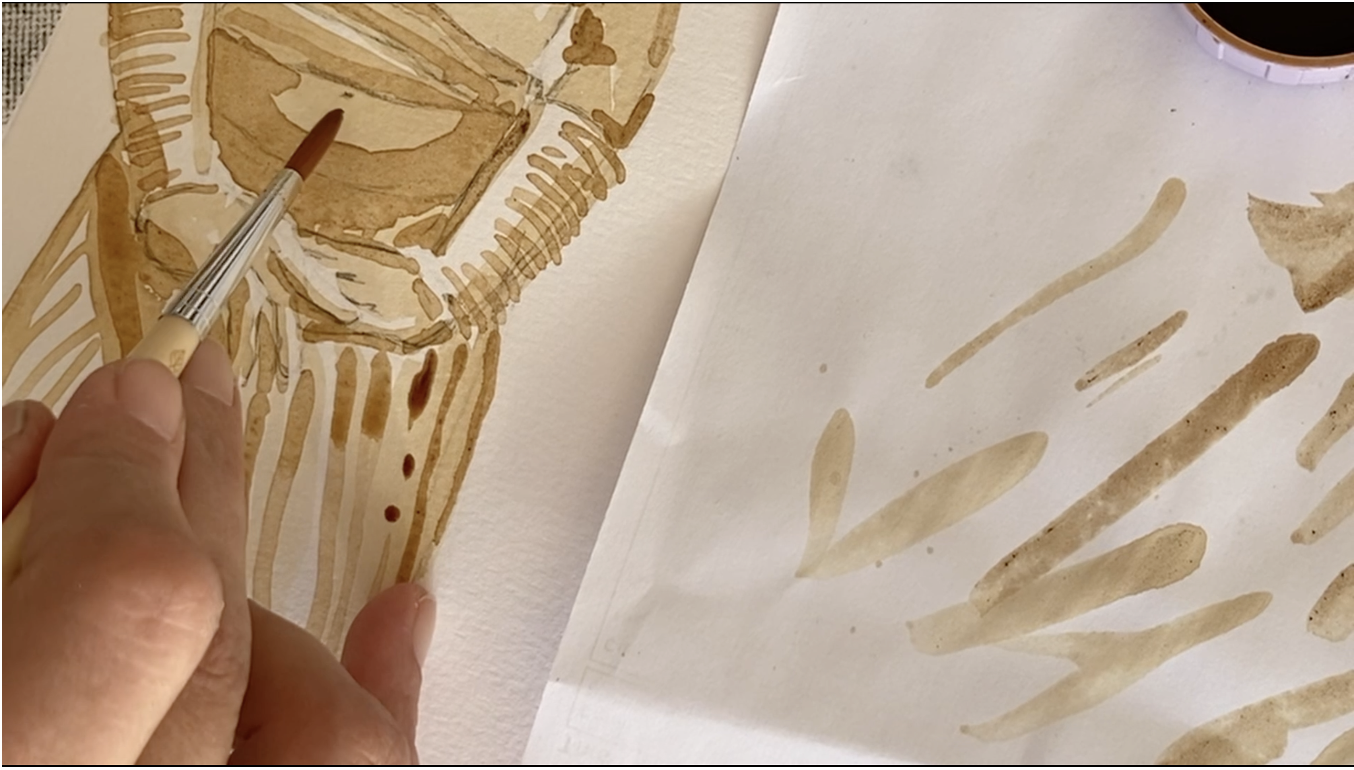

Meanwhile, I became consciously aware of the potential of coffee as a painting medium whilst studying at the University of Pretoria. I say ‘consciously’ because now, in retrospect, I realize that I was always watching my father–a historian and now retired University professor–painting and doodling with coffee and wine during informal art sessions at the dining table for most of my early years.

In 2011, during the VI Bienal de Arte residency and exhibition at CACAU on São Tomé island, I became more aware of the potential of the grain as material, understanding the geographical history of forced and ‘contracted’ labour related to its spread around the world. At this time, my main project was an installation of a humble wedding dress made of raw canvas cotton made by Abdulay Salvaterra, a São Tomense tailor, placed inside a large pan with coffee, which was lent by João Carlos Silva, from Roça (plantation) São João dos Angolares. During the first few days of the exhibition one could see the coffee slowly staining the dress, a contemplation on the process of losing and gaining one’s identity during moments of migration and resettlement.

It could be considered that the exile of the amakhosikazi to São Tomé landed them in a less visible pocket of history, as some were allegedly placed as house workers in the homes of Portuguese administrators and some were possibly forced into prostitution. This made me understand the meaning and necessity of art as a contribution to the collective effort to (attempt to) heal the collective trauma we carry as Africans in the present-day, especially its potential to explore events and the experience of people that have been less documented. By not having physical proof of an event, and in this case, documents mentioning the amakhosikazi by name and more specific physical features, one might quickly come to believe that their experience would not be remembered and that in due time would disappear completely. By trying to register this narrative, creatively and through the use of a material that would have been available in their time, I try not only to connect with them, but also to imagine them and their autonomy as part of the present.

Without delving deeply into the full world history of coffee, knowing that it was a prominent cash crop into the late 1800s makes it a material link to the story of exile of the amakhosikazi. Working with coffee from and bought in São Tomé, Mozambique and Portugal adds another layer of ‘coding’ to this work–to paint with the coffee that was grown on the land that the amakhosikazi stepped on, even if not accurate to the altitude and longitude, is to participate in the writing of their story. I do not take this lightly though as I also acknowledge that I am most likely not the most apt for this task, but take it much as J.M. Coetzee’s character Elizabeth Costello (1999) states to be the responsibility of a writer–-to function as “a secretary of the invisible”.

Painting with coffee is thus simultaneously an attempt at connecting with and transforming the past. In accepting that if there is to be space for a multitude of, many times contradicting, voices and histories, I believe there has to be a space to eventually join them, such as in a visual form. I do this consciously knowing that this process in turn will create a new imaginary that in its nature aims to mediate the voices of the past and present. This gives me hope. Not only as an African, but as a woman of Scandinavian and Indian ancestry. And this is only to name some of the labels that will need, in turn and in time, to be questioned, transformed and expanded.

Because the coffee bean is in fact the seed of the coffee plant, I see it simultaneously as a ‘historical witness’’ of a current commodity that has had its importance as a cash crop in São Tomé and for Portuguese businesses, and as a ‘living archive’, due to its relation to an older plant that might have originated in a different geography but could creatively be considered to hold the memory of experience, even if only by the stretch of the imagination. Painting with coffee is also to play with the impermanence of a work of art, which is generally avoided by museums and collectors as it can affect the work’s perceived physical value. By presenting these paintings in their digital form, and as digital reproductions, I try to overcome this fragility.

Fig.5: “Queens of the Seas-Inkosikazi II”, 2018. 29.9 x 21.1 cm. Coffee and charcoal on watercolour paper, by Maimuna Adam.

Women in Mozambican society

To see women as a continuation of the life and dealings of their fathers, brothers or husbands, is to reduce them to a position of ‘extras’, ignoring any autonomy that they might have/have had. Of course, this is not to ignore the power, or powerlessness, that many might hold or experience. Growing up on the outskirts of a Muslim community, there were moments I could feel women’s disenfranchisement the strongest, such as the hours spent focusing on food preparation from the early hours of the day. Only after I had spent hours sat in a circle of older women, while they chopped and filled large bowls with vegetables for a cousin’s wedding, did I realize that this time also had its utility, and certain empowerment, if I could use the term–it was their moment to chat, share ideas, perhaps also important information.

Fig.6: “Queens of the Seas-Inkosikazi V”, 2018. Coffee and charcoal on watercolour paper by Maimuna Adam.

It is with an imagined cooperation of women in mind that I try to look back into a past that is complex, but that I can only understand through first and second-hand accounts and images and documents. the amakhosikazi in Gungunhana’s court in the Gaza empire would have had their own level of authority, especially if one reflects on the social and political position of the queen mother as an example.

Given that one of the Portuguese government's alleged main motivations for sending the amakhosikazi into exile away from Gungunhana himself was the fact that poligamy is a crime in Portugal.

Although these are just points I am making in relation to unpacking the complexities of life for the amakhosikazi who were displaced, it is also an attempt at seeing them as human–as being able to hold more than one conflicting truth at the same time. It is my understanding that the wives of Gungunhana would have been from groups other than the Nguni. The Nguni way of conquering groups, moving them and using them to conquer others, would have created a space where this seeming paradox would be reinforced: as a conquered people they would be seen as ‘victims’ in today's language but as part of the ruling group they could be seen as ‘perpetrators’.

Mermaids

According to various sources, the Nguni held a ‘taboo’ related to going close to large bodies of water, as well as eating fish. Although this can be grasped quite logically, as they conquered land and lived off cattle, it is a point that I have chosen to carry over into the creative realm.

The amakhosikazi were exiled to São Tomé island, away from Gungunhana. I wonder: what was their own, individual, relationship to the sea? Considering that not all queens were Nguni, could it have been that the sea then represented different things to each of them, or that its meaning would change over time? In my coffee paintings I make reference to myths and deities from other parts of Africa and its diaspora, such as Mami Wata from West Africa and the African Atlantic and Iemanjá from Brasil, also known as Yemoja, the Yoruba goddess of the sea, fertility and motherhood.

Some died on São Tomean land, others managed to return to what would eventually be Mozambique and South Africa in 1911, after Gungunhana’s death in 1906. In imagining the amakhosikazi’s lives and displacements, I equally attempt to find points of connection, similarity, and difference. How can one feel the humanity of someone that could simultaneously be an ancestor and an enemy? In inviting a genealogical exploration and reflection by the public, I’m hoping that it will also bring about much needed conversations, especially between generations. As the adage attributed to Albert Einstein goes, “if you want to look to the future, know the past”, and so as futile as this exercise might feel to many, it is also one that in its process has the potential to reveal and expose how we are all connected.

Fig.7: “Queens of the Seas - Inkosikazi I”, 2018. Coffee and charcoal on watercolour paper by Maimuna Adam.

In dealing with the impact of race theory and colonization it is important to remember why these themes are important to bring up today, in 2025. If we are not aware of these, and the history of our peoples, we run the risk of repeating the same mistakes, or continue to uphold historically created power inequalities and assumptions. Here I make a call to respect and acknowledge our ancestors, and also be objective in relation to individuals in our family lineages that brought pain to us and others.

Fig.8: Still from a video of the process of painting “Queens of the Seas - Portrait of a Queen?”, 2023, by Maimuna Adam. https://youtu.be/z56vwaEuNb0 (no audio)

Picturing a universe where the amakhosikazi are the focus, rather than the man that often represented them unless they themselves held a seat of authority, I also re-imagine them as mermaids, deliberately questioning the common-held belief that the Nguni peoples believed strongly in a taboo that had them not eat fish, and not go too deeply in water. In bringing up the image of the mermaid one cannot also ignore the myth of this creature, and how it came about in the experience of sea faring people, of different origins. Independently if one considers them more akin to ‘sirens’, or a simple problem of perception created by sailors seeing water animals such as the manatee or dugong with algae on their head, seen in the distance, one can quickly understand how this mythology was created and deeply believed.

Fig.9: “Queens of the Seas-Portrait of a Queen?”, coffee on watercolour paper, 2023, by Maimuna Adam.

The ability to live both in water and on land is to me symbolic, and important for the transformative qualities of the mermaid-queens that I here depict in coffee. Although the amakhosikazi could have been from other cultures/tribes, in marrying Gungunhana they became part of the ruling Nguni group. Their influence within this group is then the next point to question–-any conclusions of which would be mere speculations. In meditating on ‘herstories’, I imagine that for the amakhosikazi to be more relatable in the present day, they would have to confront their own position.

By being presented as amphibious beings, living both on land and on water, as well as between history and myth, it is my hope that the narrative of the amakhosikazi can also be one that is accessed from the present day, as beings that through their journeys can elicit empathy and a view that even historical events and people can be re-imagined by individuals and collectives. In tapping into the forgotten or invisible desires of the individual inkosikazi, perhaps a wider analysis can be made into the female and feminine identity, and its ability to shift over time and in different contexts. Through the memory of the amakhosikazi, through the tragedy and strength that represents their exile from the continent where they were born, I draw hope that history can be treated as a living, breathing, entity.

-

This Nguni term refers to a chief’s ‘great wives’, interpreted by me as equaling the position of queens in terms of European monarchical terms. ↩

-

I’ve benefited greatly from research done by others, and am thankful to the following people and more, for their research on the topic: Prof Dr Yussuf Adam, Prof Dr Alda Costa, Prof Dr Maria Paula Meneses, Prof Dr Éric Morier-Genoud, Matilde Muocha, Júlio Machele, Prof Dr Gerhard Seibert and Dr Andrea Vacha. ↩