Background

The history of Namibia’s National Museum goes back to 1907 when it was initially established as the Landesmuseum in the pre-World War I period (Otto-Reiner, 2007). The impetus for its creation came with the arrival of a new German governor, Bruno von Schuckmann, who initiated the development of a local museum. Initially overseen by a committee predominantly composed of German nationals, the museum began to receive collections from various mission stations across the country as early as 1908. These collections encompassed a diverse array of artifacts, including diamonds, meteorites, extensive collections from San communities, and items of natural science.

The museum’s collection efforts expanded significantly, particularly towards the northern regions of the country, led by German collectors. A substantial ethnographic collection was also obtained from Schuckmannburg in the former Caprivi region, now known as Zambezi. However, the outbreak of World War I in 1914 interrupted these activities; some collections were taken over by occupying forces while others fell under the control of the South-West African administration. Certain meteorite collections were even sent to South Africa; others found their way to the British Museum.

In 1925, the institution underwent a name change to the South -West Africa (SWA) Museum, and in 1927, management of its collections was entrusted to the South-West Africa Scientific Society. Over the years, the museum saw changes in leadership, with notable acquisitions such as Captain O. Bowker’s large ethnographic collection in 1950. Renamed as the « State Museum » from 1957 to 1995, it was officially governed by South-West Africa, with Dr. A.J.D. Meiring as director under the Ministry of Education. During this period, there were significant developments in the museum’s collections, exhibitions, and infrastructure, although the predominant presence of foreign curators, particularly from Germany and South Africa, remained notable.

The museum, however, underwent major transformation in 1995 when it was rebranded as the National Museum of Namibia, five years after the country gained independence. This shift also marked the appointment of a local director, leading to an emphasis on local participation in curatorial roles and collection management.

Despite these changes, remnants of colonial influence persisted in the museum’s collections, reflecting the acquisition policies and guidelines of the colonial era. Post-independence acquisitions began, however, to reflect a greater diversity of narratives, albeit within the framework established during colonial rule. This history underscores the evolution of the museum from its colonial origins to its contemporary role in reflecting the diverse heritage and narratives of Namibia.

It is indeed notable how colonial powers established their presence in Namibia, with ethnographers, explorers, and colonial officials collecting artifacts, artworks, and cultural objects from indigenous communities. These items were often perceived through a Eurocentric lens, with little regard for the cultural contexts or spiritual significance they held within the communities of origin. The act of collecting in Namibia was deeply entwined with power dynamics, resulting in the forced extraction and relocation of numerous artifacts, many of which now reside in museums beyond Namibia’s borders, including those in Europe and South Africa, as well as within the National Museum of Namibia itself. These historical collection practices have had enduring consequences, disrupting cultural approaches and eroding the rich tapestry of indigenous traditions. The removal of these objects from their original contexts has not only diminished their cultural significance but also contributed to a fragmented understanding of Namibian history and identity, perpetuating a legacy of colonial domination and cultural loss that reverberates through the years.

This history of exclusion underscores the urgent need to rethink access to these collections and develop new modalities that prioritize the involvement and participation of the people and communities who live in Namibia today. While some collections may be restricted, community group initiatives could provide avenues for more inclusive engagement with these cultural artifacts, fostering dialogue, understanding, and ultimately, reconciliation.

Ethnographic Museums serve as repositories for historical cultural heritage, embodying the intricate tapestry of our world’s cultural diversity. These collections, painstakingly assembled over centuries, encapsulate humanity’s history, material culture, values, practices, beliefs, and traditions. However, museums face the complex task of preserving these objects within their broader social and cultural contexts. Recognising the resilience and efficacy of indigenous knowledge in conservation practices, there is a growing ideology of integrating such wisdom into museum practices. This approach acknowledges that not all communities have participated in the assembly of these collections, nor do they necessarily align with the purposes for which they were gathered. This discrepancy raises pertinent questions with which contemporary conservation efforts grapple, as they seek to navigate the ethical complexities inherent in museum collections.

The wisdom inherent in indigenous conservation practices is vividly illustrated by artifacts preserved in diverse environmental conditions, such as the 23 items recently returned from the Ethnographic Museum of Berlin, Germany, where they were housed for over a century. Despite being separated from their original contexts, these objects stand as compelling evidence of the enduring effectiveness of traditional techniques.1 Serving as tangible links to the past, they also highlight the sustainability of methods passed down through generations. This return underscores the value of integrating indigenous knowledge into contemporary conservation efforts, not only for the preservation of cultural heritage but also for fostering respect for traditional practices and promoting sustainability in a rapidly changing world.

Modern conservators are confronted with numerous ethical questions in their work, especially when dealing with historical cultural heritage. These questions revolve around who defines the standards, context, and justice in the conservation process. The answer lies in acknowledging the invaluable knowledge held by indigenous communities.

This study is of the opinion that it is time to take a lead from the communities that are living repositories of knowledge. Rather than focus on objects, attention should lie on the practitioners, creators, inventors, herbalists, and custodians of collections housed in museums today. The way forward is co-conservation, a blend of indigenous and scientific conservation methodologies. A good shift toward this change can be noted with 23 returned cultural artifacts.

The goal is to safeguard our cultural heritage, which is not just a reflection of our identity but also a mirror of the landscapes, natural resources, social practices, rituals, and economies that have shaped our communities throughout the ages. By embracing indigenous knowledge, we honour our shared history and build a bridge to a future where cultural heritage is celebrated and preserved for generations to come.

Ovahimba of “Kaoko” Kunene region

According to (Steinmetz & Hell, 2006), Ovahimba communities are part of Ovaherero who came to occupy “Kaokoland” in the early 16th Century, today the Kunene region. They migrated from Angola, where related groups still live today. The pastoralists occupied the extreme mountainous and dry parts of the area, adopting dispersed patterns of settlement, as the migration into Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa became prominent (Hangara, Kavari, & Tutjavi, 2020).

Post-independence, the social status of the Ovahimba in Namibia has seen some changes, but significant challenges persist. While Namibia’s independence in 1990 brought about hopes for greater recognition of indigenous rights and improved socio-economic conditions, the reality for many Ovahimba communities remains marked by marginalization and inequality (Likando, Haihambo, & Matengu, 2019).

One key change post-independence is the legal recognition of indigenous rights and cultural diversity in Namibia’s constitution and legislation. This recognition theoretically affords Ovahimba communities greater protection of their cultural heritage, land rights, and traditional practices. Additionally, there have been initiatives aimed at promoting education and healthcare access in rural areas where many Ovahimba reside (Likando, Haihambo, & Matengu, 2019).

By choice, Ovahimba communities have remained remarkably engaged with their traditions, including their work with hide and leather to make aprons, girdles, and headdresses. They also craft jewelry, making bracelets and neckbands out of copper wire, as well as baskets, pottery, and musical instruments (Hangara, Kavari, & Tutjavi, 2020). In many case, leatherwork is decorated with ostrich beads, copper, iron, plastic or glass beads, etc. Today, the Ovahimba are renowned for their sculptural beauty, intricately decorated hairstyles, nomadic pastoral lifestyles, leather and hide attire, and women’s red-ochre (otjize) daubed skin (Hangara, Kavari, & Tutjavi, 2020).

General heritage conservation

Heritage conservation is a crucial issue for a community, country, or continent. In Western understanding, conservation is aimed at prolonging the life expectancy of tangible cultural heritage enabling future generations to glimpse their ancestors’ ways of life and understand their identity (Caple, 2000). Contrastingly, indigenous and non-Western perspectives on heritage conservation often prioritise the interconnectedness between cultural artifacts, landscapes, and living communities. Conservation in these contexts encompasses not only the physical preservation of objects but also the revitalisation and transmission of cultural practices, oral traditions, and environmental stewardship. This holistic approach recognises the intrinsic relationship between people and their cultural heritage, viewing it as a dynamic and integral part of community identity and well-being (Schapera, 1962).

To think about alternative conservation practices to Western approaches means acknowledging and valuing a diversity of approaches to heritage preservation. It involves embracing a more inclusive and participatory framework that respects indigenous knowledge systems, engages local communities as active stewards of their heritage, and considers the interconnectedness between tangible and intangible cultural heritage. By adopting a broader perspective that integrates diverse cultural values and practices, conservation efforts can better address the complexities of preserving heritage in a rapidly changing world.

The definition provided by Guy (2016) encompasses both indigenous conservation practices and modern conservation approaches, highlighting the overarching goal of safeguarding tangible cultural heritage for present and future generations. There are, however, differences in emphasis and methodology between these two approaches. In this context, conservation is not solely focused on preserving physical objects but also on revitalizing and transmitting cultural practices and knowledge systems.

Modern conservation approaches, on the other hand, while also aiming to safeguard tangible cultural heritage, often place greater emphasis on scientific methods, documentation, and technological interventions such as preventive conservation, remedial conservation, and restoration. These approaches prioritize the physical preservation of objects and monuments through measures that respect their significance and physical properties. While modern conservation methods have made a significant contribution to preserving cultural heritage, they may sometimes overlook the importance of intangible cultural practices and community involvement.

To achieve a more sustainable approach to heritage conservation, it is essential to draw upon the strengths of both indigenous and modern conservation practices while addressing their respective limitations. This requires developing standards and guidelines that recognize the diverse cultural values and knowledge systems associated with heritage conservation. It also entails fostering collaboration and dialogue between different stakeholders, including indigenous communities, heritage professionals, policymakers, and researchers. By embracing a more inclusive and participatory framework that integrates diverse perspectives and approaches, conservation efforts can better address the complexities of preserving heritage in a rapidly changing world while respecting the significance and integrity of cultural heritage items.

Why conservation

Cultural materials change due to their physical composition, which is influenced may deteriorate according to age, damage, and/or other agents of deterioration. According to Dirksen (1997), it is difficult to conserve hide or leather objects as one must consider the nature of the material and the tanning processes used. The conditions in which the object has been conserved, used, or displayed in its lifetime should also be considered. Conservation practices for skin and leather products are usually accomplished by either interventive or preventive conservation methods (Caple, 2000). According to Badenhorst (2009), many African communities use animal fat mixed with ochre or plant saps, among other ingredients, to prolong their life span. Repair is only carried out on the most significant items, bringing their intangible values into consideration. Moreover, (Caple, 2000) also explains various other processes of conservation treatment that ensure that objects retain their original shape and appearance. Preventive conservation can be further separated into passive conservation in stable, appropriate storage environments, and proactive conservation, where the environment and item is actively monitored and intervention takes place according to changing needs.

Agents of deterioration for leather materials

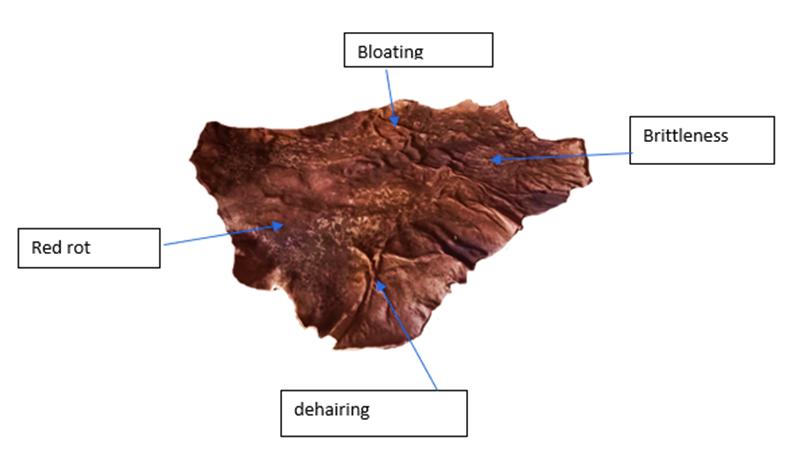

Hide and leather materials deteriorate due to different agents of deterioration. A common form of degradation in tanned leather is red rot, a form of degradation whose root causes are still unclear, but it is commonly believed that strong acids may be the cause, specifically sulfuric acid (Caple, 2000). The provenance of these acids is also unclear, as they may have been added during the tanning process or absorbed from a polluted environment, as sulphur dioxide is the main component of air pollution, (Dirksen, 1997). The effect of red rot on leather objects is irreversible and conservation measures can only slow down the decay. Other agents affecting deterioration are: excessively dry storage conditions and extreme light which tend to crack, break, or fade leather, making it brittle; exposure to high humidity which leads to mould infestation, causing staining, distorted surfaces and stuffy odors; insect infestation which causes holes and structural damage, and if the artifact has accumulated dust, insect droppings will stick to it. Both insect droppings and dust are difficult to remove. Additionally, dust particles may act as abrasives on leather or hide surfaces, so care should be taken during regular maintenance cleaning. An approach focussing on material degradation is favoured by many museums as it allows for a better understanding of the chemical processes and environmental impact on organic materials, but it does not take into account the potential cultural dimensions of these processes (Caple, 2000).

How do indigenous communities understand the process of red rot, and how do they slow down the process of degradation? According to Badenhorst (2009) hide and leather products are stored in a controlled environment to minimise contact with potential pollutants. Moreover, in southern Africa, in many cases, leather products are daubed with animal fat mixed with ochre.

Similarly, in terms of conservation, the Ovahimba communities focus on the material composition of leather products. Composite materials tend to have complex conservation issues with complex conservation needs. The material’s vulnerability and potential deterioration ultimately depends on the materials from which the product is made.

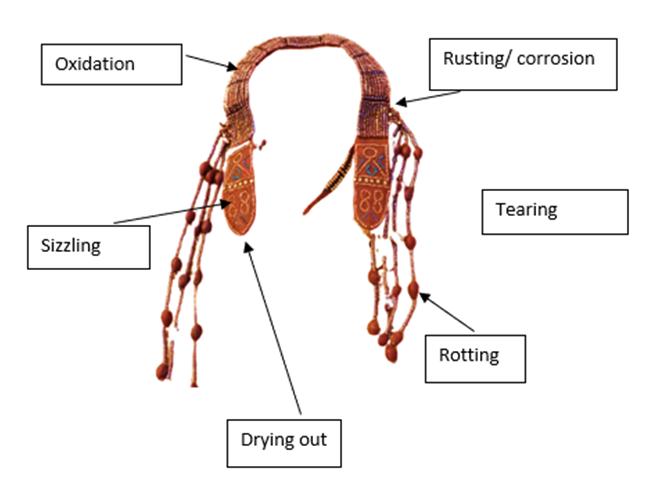

Drying out materials made from rawhide, e.g., otjinguma, is carried out using dry air as the materials are easily affected by air and sunlight. The Ovahimba communities also explain how the metals beads of materials tend to rust easily as the fat used in processing reacts with them, making the leather rigid and stiff over time. Such materials tend to be disposed of by their owners (the owner may not be necessarily the creator) when deteriorated, and new ones are then made as replacements (by a specialist craftsperson). This condition is known as “inherent vice”, scientifically explained by (Caple, 2000) as internal deterioration caused by a series factors related to materials employed, the manufacturing process used, or the combination of materials deployed. Most leather materials are also prone to wear and degradation due to age and other environmental factors, such as increased humidity, temperature, light exposure, air, dust, etc.

One woman working in leather tanning highlighted several issues affecting materials crafted from semi-tanned leather, one of which is the challenge of dehairing that impacts the quality of the leather. Other problems such as leather sizzling or warping due to glass beads, oxidation of copper beads, and rusting of iron beads, all compromise the integrity of the artifacts. Other issues include red rot, tearing, and various forms of deterioration that affect the materials’ longevity and appearance. These observations underscore the importance of addressing specific preservation challenges faced by artisans and conservators working with traditional materials like semi-tanned leather, ensuring the sustainable conservation of cultural materials.

Figure 1. An illustration of various conservation issues associated with semi-tanned leather (JN Nghishiko 2022).

Figure 2. An illustration of various conservation issues associated with fully tanned leather, which is decorated with a diversity of materials. (JN Nghishiko 2022)

Conservation measures for skin/hide products employed by ovaHimba and ovaHerero communities

“Tara ombanda yandje! Ino ozombora ndano, posia maimunika oupe uri,” says one Himba woman as she daubs Otjize paste onto an erembe. Translation: “Look, my skirt is more than five years old, and it still looks as good as new”. Leather products are conserved using different preservation methods, tailored for each type of leather and its own issue. The methods used can be described as preventive, remedial, and restorative conservation.

As a preventative measure, most materials are shaped while the leather is not completely dry, to ensure pliability, and serve storage, cleaning, and usage purposes. Post-tanning, leather materials have red ochre and a fat mixture worked into them to ensure flexibility and resistance to moisture. This is to prevent drying out, mould, insect infestation, corrosion, and red rot, all of which lead to deterioration. Other leather products, especially Ombanda/Ombuku, are made from sheep hide and semi-tanned. The leather is softer and more delicate then other types of leather, giving it a different status and significance. Such leather materials are preserved with plain fat on the fur side and subsequently smoked with a mixture of herbs, leaves, and grasses of specific species. The aim of this is to preserve from and prevent insect infestation, hair loss, and drying out. The smoke also lends a sweet scent to the leather. Smoking the materials allows them to imbibe the aromas as well as melt the animal oils and leaves them looking shiny, flexible and non-sticky. The inner side of semi-tanned materials is treated with ochre2 and a mixture of fat and oils to protect them from drying out as well as from insect infestation.

When leather products are exposed to harsh conditions, they tend to dry out more readily, requiring remedial conservation. Dry materials are moistened by steaming them, and once flexibility returns, a mixture of red ochre and fat is worked onto them (according to the type of leather). The material is then put inside an unventilated room, a special room constructed for the storage of leather materials in OvaHimba homesteads. If any materials become infested by insects, they are put in the sun and, later, smoked and daubed with Otjize paste.

When leather materials deteriorate beyond repair, they are thrown away and new ones are created as replacements. Restoration conservation is only carried out on materials of high value based on cultural significance. If for example a sheepskin Orembe, Ombuku, or otjiteta, etc, is torn, they are restored by stitching (fig.4) the torn pieces together using thread made from the bark of a Baobab tree (Adansonia digitata), animal fibre, or fibres from synthetic materials. Moreover, materials of importance that are, for example, missing a section are repaired using material similar to the original, referred to as otjipapeko. This replacement piece is chosen based on the type of leather and the tanning processes the original has undergone .

There is clearly a strong connection between hide tanning processes and leather conservation methods. As the Overhimba say: “Ounahepero tjinene okutjiwa okutja omuhoko womukova, watukwavi poo waungurwavi kokutja uyenene okutjinda nawa”, “It is important to understand how leather item was made to know how to best conserve it”.

Figure 3. A Himba woman dabbing Otjize paste onto the inner side of Ombanda to prevent it from insect infestation and drying out. (Photo: JN Nghishiko, 2022).

Figure 4. A Himba woman stitching pieces of leather materials together, that belong to a child. This process is referred to as okuyatata, remedial conservation. (Photo: JN Nghishiko, 2022)

Intangible heritage and oral tradition and their role in sustainable tanning and leather conservation for material culture

Grassby (2005) and Gazin-Schwartz (2001) describe the relationship between intangible and tangible cultural heritage, in reference to material culture and the rituals related to artifacts’ complex and difficult to interpret usage in everyday life. How artifacts communicate and transmit their context of meaning and norms applied to them is therefore created by the relationship between the materials’ tangibility and purpose, which are specific to the cultural and traditional beliefs of each community and its oral tradition.

Intangible heritage, therefore, coexists with the cultural and traditional connotations of materiality and its power defining a community is embedded in the tangible heritage created by the community.

Intangible heritage takes the form of oral traditions, rituals, initiations, and storytelling. Turner (1969) makes a reference to how communities use structures and materials with special designations and how they become connected to intangible forms through regulated motions, words, and relationships. Intrinsic to ekori headdresses, for example, worn by married women _(see figure 2)_, there are additional to the material form, determined by the choice of hide, the tanning process, its finishing and dressing processes, forms of intangibility, such as who wears it and when should it be worn, etc). Hence, artifacts have connotations related to the taboos, significance, and status rounding them in the Ovahimba culture, traditions, and belief systems. Headdresses and their uses within the community bring together inseparably linked tangible and intangible aspects.

In conclusion

Museums need to adapt their understanding of conservation to fully recognise that what is in their collections is not objects but material components of living cultures. Within this context, indigenous conservation methods offer museums a powerful means to honour and respect the rich cultural traditions and expertise of indigenous communities. These practices are deeply embedded in the heritage of communities and preserve the integrity of cultural materials, exemplified by the case of leather conservation among the Ovahimba community. These methods notably prioritize sustainability and environmental responsibility, thus contributing to museums’ long-term ecological footprint reduction. Ethnographic and cultural heritage collections, when enriched with indigenous conservation practices, become invaluable conduits for the transmission of indigenous wisdom and traditions, ensuring that valuable knowledge is passed on to future generations. Moreover, by actively engaging indigenous communities in the conservation of their material culture, museums empower these groups to have a meaningful voice in the preservation and presentation of their heritage. Additionally, the adoption of indigenous conservation practices reflects a commitment to cultural sensitivity and context, averting insensitivity and cultural appropriation in museum displays. This approach enhances the visitor experience, fostering a deeper, more authentic understanding of diverse cultures while nurturing greater cultural appreciation. Museums embracing indigenous conservation contribute to a global movement that acknowledges and honors indigenous rights and heritage, thus impacting international dialogues on cultural preservation. Importantly, in regions marked by historical mistreatment or appropriation of indigenous cultures, the adoption of indigenous conservation practices represents a crucial step towards reconciliation and healing. Such a step is fundamental in recognizing past injustices and taking concrete measures to rectify them, by allowing communities to co-conserve and rewrite their own history through practices, documentation, and contextualization.

-

The repatriation of 23 cultural belongings from Berlin, Germany, to Namibia’s National Museum is part of the project « CONFRONTING COLONIAL PASTS, ENVISIONING CREATIVE FUTURES – Collaborative Conservation and Knowledge Production of the Historical Collections from Namibia held at the Ethnological Museum Berlin and the National Museum of Namibia, Windhoek ». These objects, collected before official colonization, play a crucial role in filling gaps in Namibia’s historical and cultural narratives that require re-evaluation. They offer insights into precolonial and early colonial Namibian society, essential for decolonial processes and reconnecting Namibians with their histories. Through reconnecting these objects with their heritage communities and documenting the intangible cultural heritage emerging from this process—including historical and cultural meanings, knowledge of previous owners, creators, and users, as well as techniques for creating, caring for, and preserving such objects—the project aims to establish new and meaningful connections to Namibia’s past. ↩

-

Otjize is known as one of the ultimate cures and preventative measures for almost all conservation issues associated with leather materials. ↩